Bishop John O’Brien and his 250 year-old Irish Dictionary

19 October 2018In this month’s Library blog post, Charles Dillon, Editor of the Royal Irish Academy’s Foclóir Stairiúil na Gaeilge, examines how O’Brien’s Focalóir came about and its influence on Irish learning and lexicography.

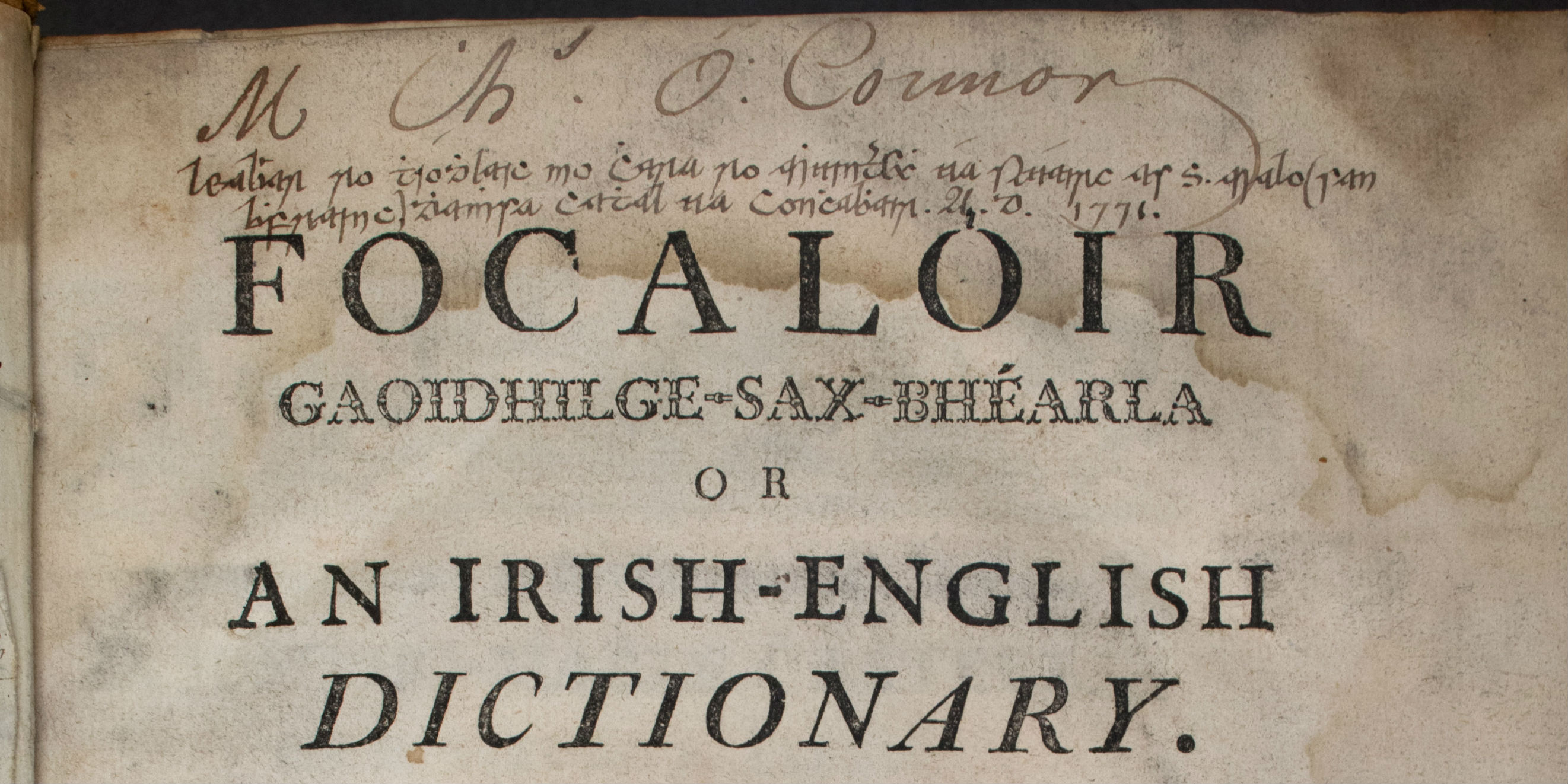

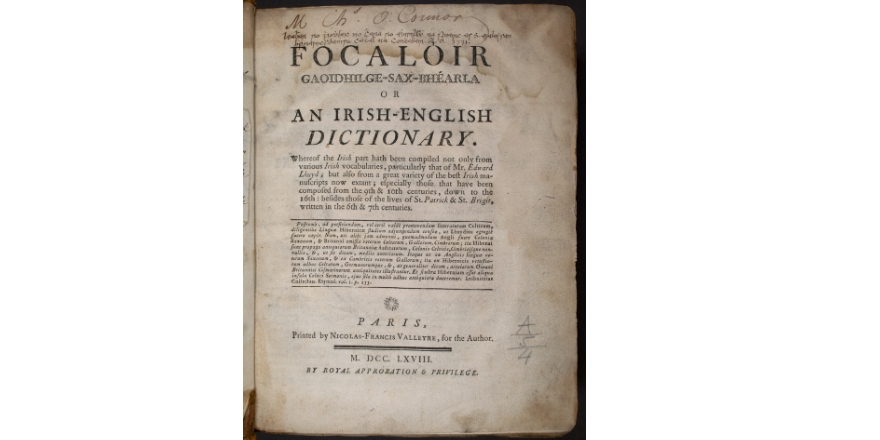

This month marks 250 years since the publication in Paris of Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sax-Bhéarla, an Irish-English Dictionary compiled by Bishop John O’Brien of Cloyne and Ross (d.1769).

Charles O'Connor's annotated copy of Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sax-Bhéarla (Paris, 1768)

Bishop John O’Brien was a well-travelled priest before he was appointed to his first Irish parish, Castlelyons and Rathcormac in 1738. He received his formal education in the Irish seminary in Toulouse, from where he graduated in 1733 as Bachelor of Divinity, and he subsequently became tutor to several eminent Irish families in continental Europe, most notably that of Col. Arthur Dillon, commander of the Dillon regiment in the French army and later Stuart ambassador to the French court. Upon O’Brien’s return to Ireland as a parish priest in his native Cork, we begin to witness his engagement with the Irish language which was the native tongue, of course, of his congregation in that area; we have three sermons he penned in 1739-40 on mortal sin, on the Gospel, and on the Passion respectively. This evident understanding of the need to preach to the populace in their vernacular is an early clue as to his motivation for producing the dictionary, for in his appeal for funding for its publication, he made the case to the authorities in Rome that it would be primarily of use to priests who were ministering to the Irish-speaking faithful.

In addition, O’Brien, like many clerics throughout Ireland at that time, was a generous and appreciative supporter of native learning and poetry, and his appointment as Bishop of Cloyne and Ross in 1748 occasioned celebratory poems from several Cork poets active at the time. Seán na Ráithíneach Ó Murchú (1700-62) welcomed the appointment with a flamboyance typical of the genre:

‘tá suairceas labhartha is aiteas ag dáimh gan chiach

i gCluain ó gairmeadh Easpog de Sheán Ó Briain.’

‘full-throated joy, acclaim and cheer abound

in Cloyne since John O’Brien was made Bishop.’

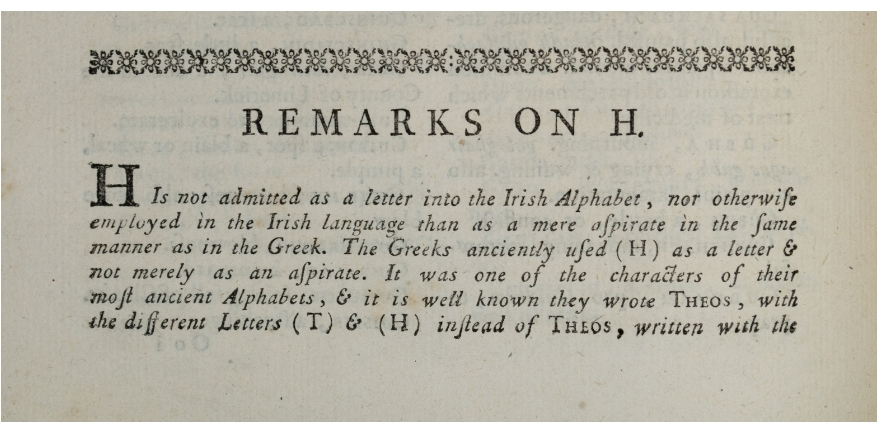

O’Brien maintained close ties with two Gaelic scholar-scribes in particular, namely Mícheál Ó Longáin and Seán Ó Conaire (he employed the former between 1759 and 1762), and these are undoubtedly the ‘persons learned in the language and antiquities of Ireland’ mentioned by O’Brien in his introductory remarks in the dictionary as his assistants in that particular endeavour. Both brought with them a considerable knowledge of the manuscript sources from which they drew a headword list for the Focalóir. This augmented the word-list compiled around 1700 by Edward Lhuyd which served as the basis of the new dictionary. Together the three made a formidable team of historian-lexicographers and their finished work was a staple resource for Irish scholars for a century after its appearance.

O'Brien's remarks on the letter H from Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sax-Bhéarla (Paris, 1768)

There are many storied copies of the Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sax-Bhéarla in various libraries and the Academy Library holds three copies, two of which show the value placed on it by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Gaelic scholars.[i] One is a copy owned by the renowned scholar Charles O’Conor MRIA (1710-91) and contains extensive handwritten annotations and notes by him. Another of the three is one that was owned by the Gaelic scribe James Stanton (fl. 1800) and which later passed into the hands of one Thomas Brosnan who sold it to the celebrated scribe, poet and diarist Amhlaoibh Ó Súilleabháin (1783-1836) of Callan, Co. Kilkenny. This copy, with the plentiful annotations and supplementary entries made by Ó Súilleabháin reflects in a very vivid way his particular vocabulary and his interests in contrast to those of the Bishop and his helpers. Ó Súilleabháin’s interjections contain everyday material related to agriculture, botany, and other country pursuits which would have been outside the ambit of O’Brien’s work, his chief sources in compiling the Dictionary being written texts, rather than the current speech of the people. Examples of Ó Súilleabháin’s additions are the entries ‘CIRCÍM, a mixture of butter and boiled eggs’; ‘CROTAL, what remains of the apples after the cyder is squeezed out’; ‘GRINNIAL, the sandy bottom under the ploughed sod’ and ‘SEASGACH, a cow having no milk’. Plant names entered include ‘BEARNÁN, dandelion’; ‘BEARNÁN BÉILTINNE, marsh-marigold’, and several plants of the pea family including the ‘PÓNAIRE FHRANCACH, French bean’, ‘PÓNAIRE CHAPAILL’ and ‘PÓNAIRE CHURRAIGH’ which are both glossed as ‘Marsh Trefoil’. Also perceived worthy of inclusion by Ó Súilleabháin is the compound noun ‘CRUINNTSEILE’ which he translates as: ‘a congregated spit; what comes from the lungs by expectoration’!

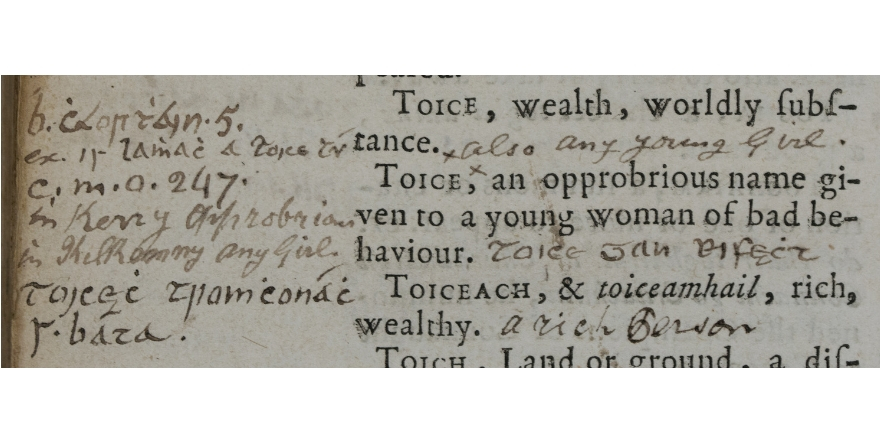

Ó Súilleabháin also feels the need at times to elaborate on O’Brien’s original definitions, especially where he feels local knowledge brings something valuable to bear. At O’Brien’s entry for Ó Súilleabháin’s home district he gives an update (in italics below):

CALLAIN, a town and territory in the county of Kilkenny, which anciently belonged to the O Glohernys, and a tribe of the Céalys. The 1st are totally extinct the 2nd of no account...

As seen below, where O’Brien has ‘TOICE, an opprobrious name given to a young woman of bad behaviour’, Ó Súillleabháin, while he acknowledges that it appears with that meaning in Merriman’s Cúirt an Mheadhon-Oidhche/Midnight Court, notices a nuance of dialect and feels the need to add the clarification ‘in Kerry opprobrious, in Kilkenny any girl.’ The later Irish lexicographer Dinneen is in agreement with Ó Súilleabháin, as he instructs us the word ‘toice’ can be ‘either affectionate or contemptuous’.[ii]

O’Brien’s dictionary was only superseded by the advent of more modern, informed techniques in philology and lexicography in the mid-nineteenth century, with the birth of the modern discipline of Celtic studies. His work is remarkable, however, for its professional engagement with Gaelic sources and the undoubted knowledge and skill which John O’Brien and his helpers brought to the task of their interpretation.

Dr Charles Dillon

Editor of the Royal Irish Academy’s Foclóir Stairiúil na Gaeilge

[i] I wish here to acknowledge the assistance of Prof Richard Sharpe who generously gave me a preview of his Clóliosta (with Mícheál Hoyne) which will be launched soon and promises to be of great help to researchers of printed books in Irish to 1871.

[ii] Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla, ed. Patrick S. Dinneen, Irish Texts Society (New edition 1927).

Follow the Foclóir Stairiúil na Gaeilge on Twitter @Focloir_RIA

Read more about Bishop John O'Brien in the Dictionary of Irish Biography