DIB entry of the day: Rupert Guinness

15 May 2019To complement the current Documents on Irish Foreign Policy (DIFP) project exhibition on Iveagh House at the National Archives of Ireland, here is the Dictionary's entry on Rupert Guinness, 2nd Earl of Iveagh by Linde Lunney.

Throughout 2019 the Documents on Irish Foreign Policy (DIFP) project is curating monthly exhibitions at the National Archives of Ireland. The May exhibition is about Iveagh House, the former townhouse of the Guinness family that has housed the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade since 1941. The Earl of Iveagh donated Iveagh House to the state (and may also have coined the phrase 'Guinness is good for you'!).

Rupert Edward Cecil Lee Guinness (1874–1967), 2nd earl of Iveagh, agriculturalist, businessman, and philanthropist, was born 29 March 1874 in London, eldest among three sons of Edward Cecil Guinness, of the wealthy brewing family, who was created 1st earl of Iveagh in 1919, and his wife Adelaide Maria (d. 1916), daughter of Richard Samuel Guinness, MP, of Deepwell, Co. Dublin. His parents were second cousins once removed, both descended from Arthur Guinness, and thus related to many prominent people in business, the clergy, and the gentry. Sir Benjamin Lee Guinness was Rupert's grandfather, Arthur Edward Guinness, 1st Baron Ardilaun, was an uncle, and Walter Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne, was Rupert's younger brother. Rupert Guinness was a pupil at Eton College, but found schoolwork difficult, probably as a result of what would now be diagnosed as dyslexia, not then recognised. However, he displayed an interest in the practical aspects of science in Eton, and also later when he spent an otherwise unprofitable year as a student in Trinity College, Cambridge.

He and his brothers learned to row on the lake at Farmleigh, adjoining the Phoenix Park, Dublin, their home in Ireland. Rupert Guinness became an outstandingly powerful rower, and he won the Ladies, Plate at Henley in 1893. He won the Diamond Sculls at Henley in 1895 and again in 1896, in which year he also won the Wingfield Sculls, making him the undisputed leading amateur oarsman of his day. He was president of the Thames Rowing Club from 1911 until his death. In 1903 he won the King's Cup at Cowes regatta and the Vasco da Gama Challenge Cup in Portugal with a 90-ft (27.4 m) racing yawl he had had built. In that year he was asked by the admiralty to oversee the establishment, equipping, and training of a planned Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. Guinness rapidly and successfully laid the groundwork for the organisation, and set up what became the London Division of the RNVR. Around a thousand men in the RNVR, with Guinness as commander, played an important role in the first world war, though disappointed to be employed only on duty on shore. Guinness was ADC (1916–19) to King George V, and was sent to Canada to encourage recruitment for the Royal Navy. His wife turned their large London house into an office to coordinate welfare work on behalf of British prisoners of war.

Political career and public life Guinness had already seen active service (1899–1900) in the Boer war. His father had donated a field hospital, known as the Irish Hospital, to help the war effort, and Rupert Guinness went to South Africa as adjutant to the surgeon in charge, Sir William Thomson. The hospital was very successful in dealing with outbreaks of typhoid fever. Guinness was mentioned in dispatches, and in 1901 was awarded the CMG. On returning to England from South Africa, he became interested in politics, and was a member of London county council 1904–10. He was not elected for the Haggerston division of Shoreditch when he stood as a conservative candidate in 1903, but was successful in that constituency in a by-election in 1908. In 1910 he was not re-elected, but in 1912 he became MP for the south-eastern division of Essex (later known as the Southend constituency). He remained the MP there until the death of his father in 1927. Rupert Guinness then became 2nd Lord Iveagh, and took his seat in the house of lords, where he occasionally spoke. His wife Lady Gwendolen was elected in his place and sat in parliament until her retirement (1935). She was succeeded as MP by her son-in-law, Henry Channon, succeeded in turn by his son, a grandson of Rupert and Gwendolen Guinness, a family succession unusual in modern British politics.

Guinness, though not particularly prominent in the commons, was a popular and hard-working constituency MP, who lived for long periods in a working-class area of the east end of London, getting to know the constituents and their concerns. His experience in the Boer war and with the RNVR had already given him an insight into aspects of life not often encountered by people of his class. In 1910, after a visit to Canada, he decided that the dominion, as well as people from Britain who planned to emigrate, would all be better served if the new settlers had more experience in agriculture. He set up a training programme on a farm he bought near his own country estate in England, and enabled more than 200 intending emigrants to acquire skills relevant to Canadian conditions. The scheme could not be continued after war broke out in 1914. He had a longstanding interest in preventive medicine, and in particular in the development of vaccines to combat diseases such as the typhoid that he had encountered in South Africa, and he helped his friend Sir Almroth Wright establish a bacteriology laboratory in St Mary's Hospital, London. In 1928, when Wright's work needed more funding and larger premises, Lord Iveagh gave £40,000, as well as providing other, equally valuable, forms of support, to help establish what later became the Wright-Fleming Institute, where Sir Alexander Fleming was to discover penicillin.

Agriculture Scientific aspects of agriculture were to dominate the middle years of Guinness's life, and he is credited with helping bring about major improvements in food-related public health, often by improving animal health. His friendships with Wright, Thomson, and Fleming gave him an awareness of contemporary developments in bacteriology, and this, along with his own practical understanding of animal husbandry and disease control, led him to work for the provision of clean milk, at first from his own farm at Pyrford, Surrey, and later from his huge estates at Elveden, inherited from his father. The dangers of milk contaminated by bacteria, and in particular the risk from bovine tuberculosis, were increasingly understood in the twentieth century, and as early as 1914 he installed sterilising equipment for bottling operations at Pyrford. Guinness, known at that time by the courtesy title of Viscount Elveden, was one of the founders and first chairman of the rather carelessly named Tuberculin-Tested Milk Producers’ Association in 1920. The programme for the eradication of bovine tuberculosis has been outstandingly successful, with resulting immense benefit to consumers’ health. Elveden was also influential in the newly established Dairy Research Institute at Reading University, providing funding, helping in the establishment of an experimental farm at Shinfield, and serving as chairman of its governing body. He was actively involved in groundbreaking research on animal lactation, nutritional composition of milk, and prevention of mastitis.

Halfway through the first world war, Guinness was asked by the Ministry of Agriculture to stop working for the RNVR, and instead to try to improve food production in Britain to support the war effort. After his demobilisation, he used his Pyrford estate to show how yields of clean milk could be greatly increased, with resultant benefits especially for the health of children. His achievements in later years at Elveden, in Suffolk, were on an almost heroic scale. Over 23,000 acres of very poor land, practically heathland, which when he inherited it in 1927 was used mainly and at huge cost as a sporting estate, were turned into England's biggest dairy farm, a showplace for the possibilities of scientifically based agriculture, and a success in economic terms alone. He and his team of managers and tenants systematically experimented with, and gradually implemented, new techniques of animal and land husbandry, helping to popularise the use of lucerne, for instance, for soil improvement and animal feed. Elveden's success is cited as having influenced the adoption throughout the whole of British agriculture of such practices as combine harvesting, electric fencing, sugar-beet growing, and silage-making.

Again in the second world war, Iveagh was central to the national efforts to increase domestic food production; milk production at Elveden went from a pre-war total of 100,000 gallons annually to 250,000 gallons in 1945, fallow lands were ploughed up for crops, and his level of stocking per acre increased commensurately. Not surprisingly, when the Ministry of Defence requisitioned thousands of expensively reclaimed acres of Elveden as a tank training range, Iveagh was furious, and lobbied until the decision was eventually reversed, though a great deal of damage had been done to the land. In the early 1950s a similar threat had to be fought; the forestry commission tried to purchase compulsorily 3,000 acres of Elveden's most productive land for reafforestation. The case eventually went before parliament, and Iveagh's objections were upheld. In the years after the war Iveagh continued to support, financially and otherwise, agricultural research at several institutions – for instance, at Chadacre Agricultural Institute, of which he was chairman, and notably at Rothamsted, where his interest fostered important experiments on ensiling of crops, composting techniques of utilising straw, and dealing with manure. On his own farm at Pyrford, it was discovered that enough methane gas could be produced from composting waste to be used for local heating; this discovery was not at the time regarded as important, since people believed that existing methods of power generation were adequate and more cost-effective.

Business activities One of Iveagh's particular interests at Elveden was the breeding of improved strains of barley, and he wrote a short paper (1959) on experiments carried out in Ireland and England to breed in better brewing quality. By then he had been chairman of the family brewing company, Arthur Guinness & Son Ltd, for thirty-two years, since his father's death in 1927 (and had been a director for sixty years, since 1899). The chairmanship had passed from father to son for five generations; in his stewardship of the huge enterprise Rupert Guinness was in his own way as innovative as any of his forbears, though not so much involved in the day-to-day running of the business. As chairman he was responsible for taking some major decisions which enabled the company to maintain profitability through difficult economic conditions. He was particularly involved with the decision to brew Guinness stout for the first time outside Ireland, and a huge plant was opened (1936) at Park Royal, west London. He oversaw major expansion into a worldwide market, as well as diversification of products and production methods. Perhaps equally important was his appreciation of the importance of advertising, and he initiated the trend-setting campaign carried out for the company in the 1930s, with the famous slogan ‘Guinness is good for you’, and instantly recognisable artwork. He possibly coined the slogan, and may even have been the model for the cheerful face in the advertisements. He also sanctioned the publication of the Guinness book of records, compiled annually since 1955, which almost immediately became a publishing phenomenon in many languages and versions. He was actively involved in planning a museum of scientific instruments and brewing technology, which he opened in Dublin shortly before he died.

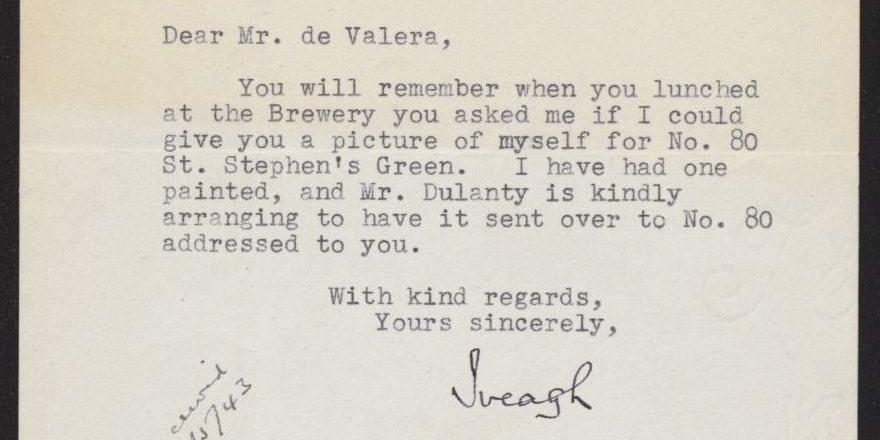

Philanthropy As well as the support for medical and agricultural research outlined above, Iveagh continued to assist the work of the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, founded by his father, and he continued the development of the Iveagh Trust, a Dublin charity to provide better inner-city housing, also founded by the 1st earl. Lord Iveagh and the Guinness company gave large sums of money to hospitals and universities in Dublin and the UK, and, as chancellor of Dublin University, Lord Iveagh attended annual graduation ceremonies in TCD (1927–63). In 1939 he gave his magnificent Dublin residence, Iveagh House, to the Irish government, and it was used to house the then Department of External Affairs. The government leased Iveagh Gardens to UCD. It later became a public park, like St Stephen's Green close by, which had been given to the city of Dublin by his uncle Lord Ardilaun.

Lord Iveagh's significant contributions to agriculture, medicine, and public life were recognised and honoured in many ways. He was made a CB (1911), and was accorded the signal honour of a knighthood of the Order of the Garter (1955). He was awarded an honorary degree of D.Sc. by Reading University (of which he became chancellor), in recognition of his work for the Institute of Dairy Research. He received honorary LLD degrees from TCD and NUI, and in 1964 was elected FRS. In 1958 he was awarded the first Bledisloe gold medal from the Royal Agricultural Society for outstanding agricultural achievement.

On 8 October 1903 he and Lady Gwendolen Florence Mary Onslow were married at St Margaret's, Westminster. She was the elder daughter of the 4th earl of Onslow, and was well educated, very able, and as energetic as her husband. Throughout their long married life they shared interests and worked together in politics, in agriculture, in charities, and in work for the armed forces and prisoners of war. They travelled together to Canada and India on lengthy trips to investigate best practice in education and research. Their firstborn son died when only a few days old, in 1906. The second son, Arthur Onslow Edward Guinness (b. 1912), was killed in action in 1945, a great loss to his family and to the future of the Guinness company. Lord Iveagh stayed on as chairman of the company into his eighties, delaying retirement until 1962, when his grandson was old enough to take over. Lord and Lady Iveagh also had three daughters, one of whom married (1945) a prince of the Prussian royal family. Lady Iveagh died 16 February 1966, and her husband died 14 February 1967. They are buried at Pyrford, close to the farm which was so important in both their lives.

The DIFP exhibition on Iveagh House is on display throughout May 2019 in the lobby of the National Archives of Ireland, Bishop Street, Dublin 8, which is open from 9.30am to 5pm Monday to Friday; find out more on the DIFP blog.

Image courtesy of the National Archives of Ireland.

Article sources: H. D. Kay, ‘Rupert Edward Cecil Lee Guinness, second earl of Iveagh 1874–1967’, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, xiv (1968), 287–307; DNB; WWW; Burke, Peerage (1999), 1520

© 2019 Cambridge University Press and Royal Irish Academy. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Learn more about DIB copyright and permissions.