Printers’ devices from the Royal Irish Academy's early print collections: Johannes Hamman.

23 December 2019This is the first in a series of posts exploring printers’ devices in the early printed books of the library’s collections.

Logos are ubiquitous; we can identify a company or institution at a glance by just a symbol or a font type. The ‘tick’ on the side of a running shoe, the penguin on the spine of a book. From the earliest days of print history, printers and publishers used devices in very much the same way, to mark ownership, to advertise and as a mark of quality. Printers’ devices, also known as printers’ marks, are made up of a woodcut illustration, a motto or initials or all three. Some are more elaborate than others, as we shall see in this series of posts. They are usually found above the imprint on the title page of a book or on the final leaf.

The first known printer’s device appears in Fust and Schoeffer’ Mainz Psalter in 1457. It is positioned after the colophon[i] and is made up of two shields hanging from a branch. The Greek symbol X for Christ is inscribed on the first shield and the Greek letter A for logos (word) on the second.

The printers’ device is not a remnant of the manuscript book tradition; it is only with the invention of the printing press and the beginning of mass production of printed material that such an addition proved useful. However, the origins of the printers' device predates the invention of print and typography. Early Medieval merchants would use distinctive marks on their produce and the earlier devices are reminiscent of these symbols. These merchants’ marks, or ‘housemarks’, were quite simple and usually in the shape of the number 4. The earlier printers’ devices often used the number 4 as a base with a combination of strokes or curves, often with intials and an orb and cross. The first device we will look at in this series shows clearly how the printer developed his mark from the established merchants’ marks.

Johannes Hamman de Landoia

Johannes Hamman, also known as Hertzog, was a printer from Landau, Germany. There are about 85 known works by Hamman c.1482-1509, mostly printed in Venice. He often collaborated with fellow Germans, including Johann Emerich on a number of liturgical texts.

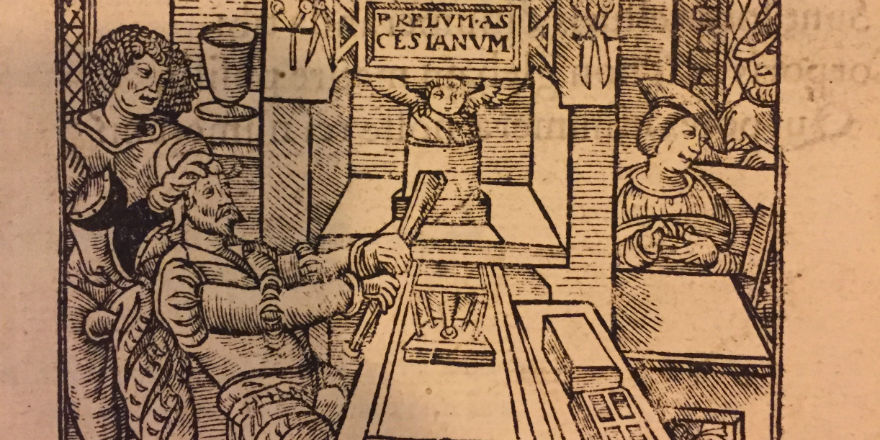

Hamman’s device is made up of his initials I. H. within an orb and cross surrounded by an elegant leaf design on a black background. The orb and cross, globus cruciger, has been a symbol of Christianity since the Middle Ages. It is the representation of Christ’s dominion over the world. In the lower portion of the orb are a reversed ‘4’ mark with a cross and reversed ‘C’. This could possibly represent Hamman’s ‘merchant’s mark’ or ‘housemark’. He was the first in Italy to combine the ‘4’ mark with the orb and in this case the monogram, indicating his German origins, as this was a feature of German printers rather than Italian.

Hamman's device located on the final page under the colophon of Epytoma Joannis de Monte Regio in Almagestum Ptolome by Joannes Regiomontanus (Venice, 1496) RIA SR 24 F 19.

Life, the universe and everything ...

In the Library’s incunabula [ii] collection we find this device in a very important early scientific work entitled Epytoma Joannis de Monte Regio in Almagestum Ptolome by Joannes Regiomontanus. The Epytoma is an abridged version of Ptolemy’s Almagest, an astronomical textbook written about AD 150 establishing his model of a geocentric universe, a model which was followed for over a thousand year.

Austrian astronomer and mathematician, Georg von Peuerbach, began his new Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Almagest in 1460 but died before it was completed, the task was taken on by his pupil Regiomontanus. The book was eventually printed on 31 August 1496 in Venice by Hamman, twenty years after Regiomontanus’ death. The Epytoma is the first printed edition of Ptolemy’s Almagest; it also discussed newer observations and developments in the field of astronomy and drew attention to some of the problems with Ptolemy’s theories. It became an important reference tool for astronomers, including Copernicus, who consulted a copy of the book and began to question Ptolemy’s calculations and so set in motion his re-envisaging of the solar system.

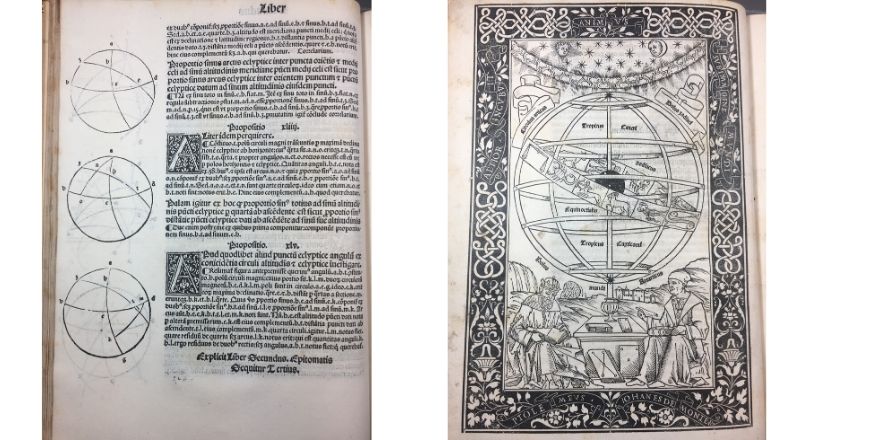

This early printed book contains some relatively interesting and complex printing techniques. It has a xylographic title page, which is the technical term for a woodcut title. It also has numerous marginal diagrams throughout and decorative woodcut initials.

Xylographic title page and decorative initial. Epytoma Joannis de Monte Regio in Almagestum Ptolome by Joannes Regiomontanus (Venice, 1496) RIA SR 24 F 19.

The most elaborate feature of this book is the full-page woodcut depicting Ptolemy and Regiomontanus under an armillary sphere with the moon, sun and stars above. Ptolemy, sits to the left reading a book on his lap, opposite sits Regiomontanus pointing and possibly questioning him. They represent ancient and modern science in dialogue.

Marginal diagrams and full page woodcut illustration. Epytoma Joannis de Monte Regio in Almagestum Ptolome by Joannes Regiomontanus (Venice, 1496) RIA SR 24 F 19.

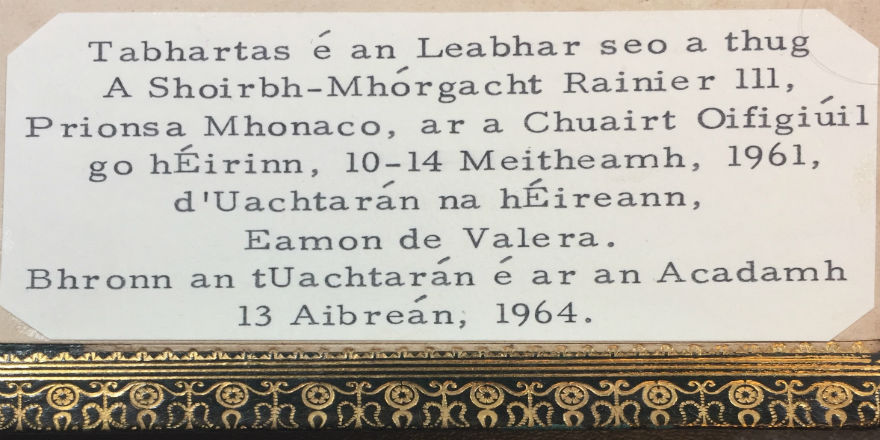

The Library’s copy has an additional interesting feature – its provenance. This Book was a gift given by His Excellency Rainer III, Prince of Monaco, to the President of Ireland, Eamon de Valera, on his Official Visit to Ireland, 10-14 June, 1961, in reocognition of his mathematical interests. The President, a member of the Academy, presented it to the Academy for the Library collections on 13 April, 1964.

We shall continue to explore more of our early printed books in future posts, so stay tuned!

Sophie Evans

Assistant Librarian

Further Reading:

Hugh William Davies, Devices of the early printers, 1457-1560 : their history and development, with a chapter on portrait figures of printers (London, 1935)

Alfred W. Pollard, Fine Books (London, c.1912)

Centre de Recursos per a l'Aprenentatge i la Investigació / Universitat de Barcelona. (2019); available online at: https://crai.ub.edu/sites/default/files/impressors/cerca_eng.htm (Accessed 25 Nov. 2019).

William Roberts, Printers' marks: a chapter in the history of typography by W. Roberts (London, 1893); available online at:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25663/25663-h/25663-h.htm#fig40b (accessed 25 November 2019).

[i] Colophon: Inscription at the end of a book containing information on its production – printer’s name, place of publication, date etc.

[ii] Incunabula: Books printed before 1501.