Celebrating Irish women: Constance Markievicz

03 February 2020The Royal Irish Academy is hosting an exhibition in celebration of Irish women running from St Brigid’s Day (1 February) to International Women’s Day (8 March). One of the remarkable women featured is Constance Markievicz.

Constance Georgine Markievicz

by Senia Paseta

Constance Georgine Markievicz (1868–1927), Countess Markievicz, republican and labour activist, was born 4 February 1868 at Buckingham Gate, London, eldest of the three daughters and two sons of Sir Henry Gore-Booth of Lissadell, Co. Sligo, philanthropist and explorer, and Georgina Mary Gore-Booth (née Hill) of Tickhill Castle, Yorkshire. She was taken to the family house at Lisadell as an infant, and retained a strong attachment to the west of Ireland despite her frequent sojourns in Dublin and abroad.

She was born into a life of privilege. Descended from seventeenth-century planters, the Gore-Booths were leading landowners who entertained lavishly at Lissadell, and enjoyed country pursuits including riding, hunting, and driving. An active and demonstrative child, she was known for her skill in the saddle and for her friendly relations with the family's tenants. She and her favourite sister, Eva, were brought up in a manner that reflected their class and social standing. They are recalled as ‘two girls in silk kimonos’ in the poem ‘In memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz’ (October 1927) by W. B. Yeats. Educated at home, they were taught to appreciate music, poetry, and art, and in 1886 they were taken by their governess on a grand tour of the Continent. Constance made her formal debut into society in 1887 when she was presented to Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace.

She hoped to study art, but faced opposition from her parents who disapproved of her ambition and refused to fund her studies. They finally relented in 1893, and she went to the Slade School of Art in London. On her return to Lissadell, she took up the cause of women's suffrage, presiding over a meeting of the Sligo Women's Suffrage Society in 1896. But she remained interested in art, and in 1898 her parents were persuaded to allow her to go to Paris to further her studies. While in Paris she met fellow art student Count Casimir Dunin-Markievicz, a Pole whose family held land in the Ukraine. They were married in London in 1900 and a daughter, Maeve, was born the following year. The couple returned to Paris in 1902, leaving their daughter in the care of Lady Gore-Booth. The family was reunited in Dublin in the following year, but from about 1908 Maeve lived almost exclusively with her grandparents at Lissadell.

Markievicz and her husband became involved in Dublin's liveliest cultural and social circles, exhibiting their paintings, producing and acting in plays at the Abbey Theatre, and helping to establish the United Arts Club. She and her husband separated amicably about 1909. Her conversion to Irish republicanism dates from about 1908 when she joined Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland). She also helped to found and became a regular contributor to Bean na hÉireann (Woman of Ireland), the first women's nationalist journal in Ireland. She continued to advocate women's suffrage, but devoted most of her time to overtly nationalist causes such as the establishment in 1909 of the Fianna Éireann, a republican youth movement. By 1911 she had become an executive member of Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and was arrested that year while protesting against the visit to Dublin of George V.

Markievicz became increasingly interested in socialism and trade unionism. She spoke in 1911 at a meeting of the newly established Women Workers' Union and remained a strong supporter. An advocate of striking workers during the lock-out of 1913, she organised soup kitchens in the Dublin slums and at Liberty Hall. Markievicz became an honorary treasurer of the Irish Citizen Army, and was instrumental in merging Inghinidhe na hÉireann with Cumann na mBan, a militant women's republican organisation which was established to support the Irish Volunteers. Fiercely opposed to Irish involvement in the British war effort, she co-founded the Irish Neutrality League in 1914, and supported the small minority who split from the larger Volunteer organisation over the issue of Irish participation in the war. She remained active in labour circles, co-founding in 1915 the Irish Workers' Co-operative Society, while also participating in the military training and mobilisation of the Citizen Army and the Fianna.

An aggressive and flamboyant speaker who enjoyed wearing military uniforms and carrying weapons, Markievicz was known for her advocacy of armed rebellion against British authority. She welcomed the Easter rising, acting as second-in-command of a troop of Citizen Army combatants at St Stephen's Green. As British troops occupied buildings surrounding the park, it became a deathtrap for the Citizen Army who were forced to seek refuge in the College of Surgeons. After a week of heavy fire, Markievicz and her fellow rebels surrendered. She was originally sentenced to death for her part in the rebellion, but this was commuted on account of her sex; she was transferred to Aylesbury prison and was released under a general amnesty in June 1917, having served fourteen months. While being held at Mountjoy prison just after her surrender, she had begun to take instruction from a Roman Catholic priest, and shortly after returning to Ireland she was formally received into the church. Notoriously ignorant of the finer points of catholic theology, she none the less embraced her new faith wholeheartedly, claiming to have experienced an epiphany while holed up in the College of Surgeons.

Markievicz threw herself behind Sinn Féin: she was elected to its executive board and was one of the many advanced nationalists arrested in 1918 on account of their alleged involvement in a treasonous ‘German plot’. During her incarceration, she was invited to stand as a Sinn Féin candidate for Dublin's St Patrick's division at the forthcoming general election. She was the first woman to be elected to the British parliament, but like all Sinn Féin MPs she refused to take her seat at Westminster. On her release and return to Ireland in March 1919, she was named minister for labour in the first Dáil Éireann, a position that bridged her commitment to labour and to the fledgling republic. Arrested again in June for making a seditious speech, she was sentenced to four months hard labour in Cork, the third time she had been incarcerated in four years. After her release Markievicz continued to defy British authorities by maintaining her work for Sinn Féin and the dáil. Such political activity became more dangerous and difficult after the outbreak of the Anglo–Irish war in early 1919 and Markievicz spent much of this time on the run and in constant danger of arrest. She was arrested again in September 1920 and sentenced to two years' hard labour after a long period on remand. Released in July 1921 in the wake of a truce agreed between the British government and Irish republicans, she returned to her ministry, but any hope of political stability was dashed by the split in republican ranks over the Anglo–Irish treaty of December 1921. Dressed in her Cumann na mBan uniform, Markievicz addressed the dáil in a characteristically theatrical fashion, condemning the treaty and reiterating her advocacy of an Irish workers' republic. Reelected president of Cumann na mBan and chief of the Fianna in 1922, she reaffirmed her opposition to the treaty through those organisations.

As an active opponent of the treaty, Markievicz refused to take her seat in the dáil and was once again forced to go into hiding while former comrades became embroiled in a civil war. She composed anti-treaty articles and continued to engage in speaking tours to publicise the republican cause. Elected to the dáil for Dublin South in August 1923, she refused to take the oath of allegiance to the king and, like other elected republicans, she thus disqualified herself from sitting. She was arrested for the last time in November 1923 while attempting to collect signatures for a petition for the release of republican prisoners, and went on hunger strike until she and her fellow prisoners were released just before Christmas. Removed from parliamentary politics and increasingly detached from her former republican colleagues – some of whom remained suspicious of female politicians and of Markievicz in particular – she remained committed to the republican ideal, producing numerous publications which focused more on former glories than on disappointing contemporary realities. She joined Fianna Fáil when it was established in 1926, finally breaking her ties with Cumann na mBan, which opposed the new political party. She stood successfully as a Fianna Fáil candidate for Dublin South at the June 1927 general election, but hard work and often rough conditions took their toll, and her health began to fail. She was admitted to Sir Patrick Dun's hospital and, declaring that she was a pauper, was placed in a public ward, where she died on 15 July 1927; she was buried in Glasnevin cemetery.

Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper, Prison letters of Countess Markievicz (1934); Brian Farrell, ‘Markievicz and the women of the revolution’, F. X. Martin, Leaders and men of the Easter rising: Dublin 1916 (1967), 227–303; Anne Marreco, Rebel countess: the life and times of Countess Markievicz (1967); Jacqueline Van Voris, Constance Markievicz: in the cause of Ireland (1967); Sean O'Faolain, Constance Markievicz (1968); Elizabeth Coxhead, Daughters of Erin: five women of the Irish renaissance (1969); Eibhlin Ní Éireamhoin, Two great Irish women: Maud Gonne MacBride and Countess Markievicz (1971); Margaret Ward, Unmanageable revolutionaries: women and Irish nationalism (1983); Anne Haverty, Constance Markievicz: an independent life (1988); Diana Norman, Terrible beauty: a life of Constance Markievicz (1988)

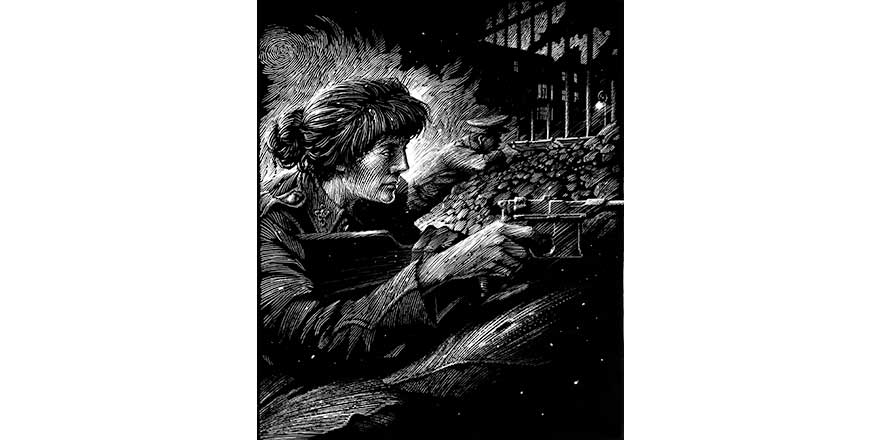

Illustration by David Rooney. Copyright: RIA

Constance Markievicz features in 1916 Portraits and Lives, edited by James Quinn and Lawrence William White, and illustrated by David Rooney. Special exhibition offer: €20 (RRP €30). A limited edition print of Countess Markievicz, numbered and signed by the artist, is also available to purchase at the special price of €60 (RRP €125). Offer ends 8 March.