Documenting a conquest: The RIA copies of the ‘Books of Survey and Distribution’

07 February 2020For this month’s Library blog post, Dr John Gibney, Assistant Editor with the Royal Irish Academy's Documents on Irish Foreign Policy series, looks at an important seventeenth-century document from our collections.

The ‘Books of Survey and Distribution’ record one of the fundamental consequences of the seventeenth-century conquest of Ireland; and the Royal Irish Academy has a set of them.

The first of those statements sounds dramatic, and at first glance you might be forgiven for wondering what the fuss is about when you see what the books contain: lists of landowners and landholders, along with the size of their holdings. Yet these relatively plain manuscripts reveal a revolution. During the 1650s, in the aftermath of the intertwined British and Irish civil wars of the 1640s and the devastating reconquest of Ireland by the English parliament, vast quantities of Irish land was confiscated from Irish Catholics (who were deemed to have been in rebellion), in order to pay for the parliamentarian war effort. The Books of Survey and Distribution record the outcome.

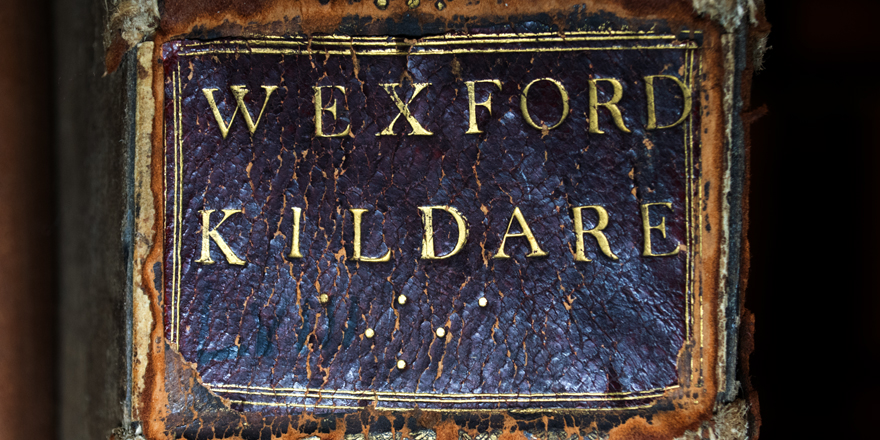

The Irish Manuscripts Commission published editions of four of the books held in the pre-1922 Public Record Office (which are now in the National Archives). The RIA copies consist of ‘sixteen splendid volumes in folio ruled in red ink and written with the greatest neatness and accuracy in period size’. They were purchased by the British Government in 1883 from the library of the duke of Buckingham, and are copies originally composed in 1677 at the behest of Arthur Capel, earl of Essex (1631-83), lord lieutenant of Ireland from 1672 to 1677 (who eventually cut his own throat while imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1683). Essex, in correspondence, had no problem describing Ireland as a ‘plantation’, so what do the records he had copied reveal?

Bookplate of Algernon Capel, 2nd earl of Essex, from the RIA volumes, which had been commissioned by his father.

In a nutshell, they are records of landownership. Between 1640 and 1670 the proportion of land in Ireland owned by Catholics went from 42.2% to 16.6%, while the proportion owned by Protestants jumped from 42.1% to 69.8%. A new wave of British settlers had obtained lands in Ireland that had been confiscated and redistributed by the Cromwellian authorities in the 1650s; and equally, many of those who had settled in earlier waves of colonisation acquired lands and consolidated their wealth and status in a new order. The Jacobean plantation of Wexford is a case in point. The plantations of Ulster and Munster are the most well-known British colonisation projects in Ireland, but there were many other, smaller plantation schemes, and the plantation of Wexford was the first of these.

Beginning in 1618, North Wexford witnessed a dramatic shift in land ownership, as land deemed to be in the gift of the crown was granted to a mixture of military veterans and administrators under specific conditions, such as undertakings to fortify the new settlements that were to be established (uniquely for a plantation scheme in this era, no new British grantees were involved). The proportion of land in the hands of the ‘New English’ (the newer, largely Protestant settlers of the early modern period) went from 14% to 50%, while the share of land belonging to those descended from the original medieval settlers (the so-called ‘Old English’) went from 11% to 14%. The proportion of Irish-owned land dropped from 75% to 36%.

Spine title from the Books of Survey and Disctribution. Vol 2. County Wexford and County Kildare (RIA MS G iii 2)

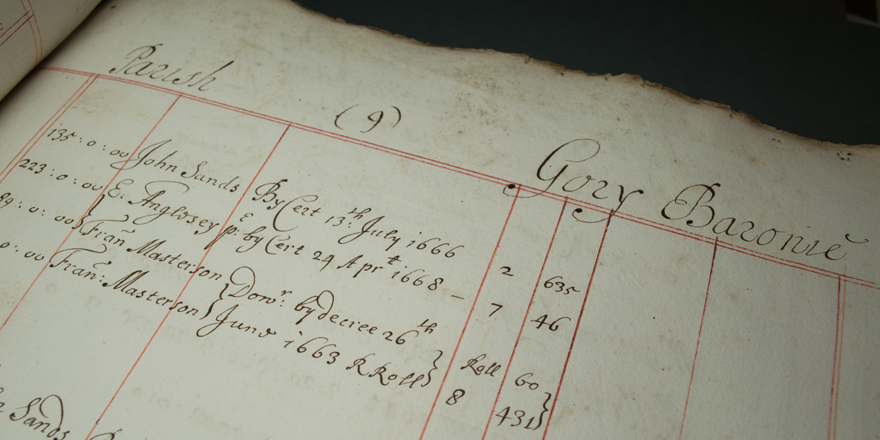

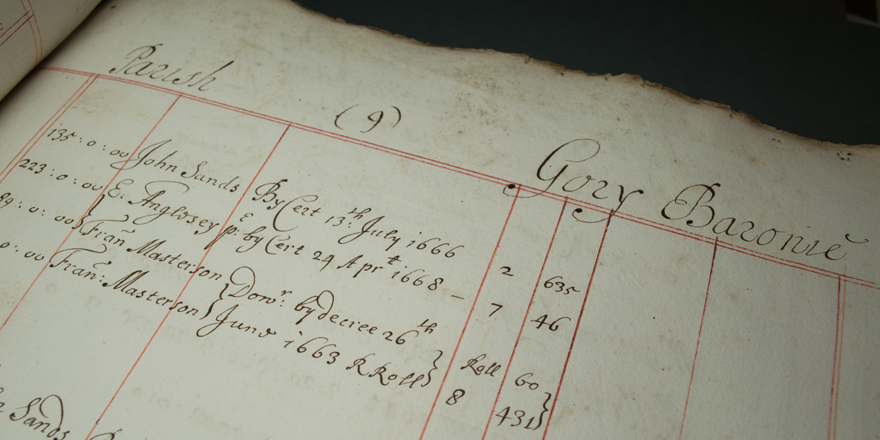

It also appears that land clearances took place: in the 1620s complaints were made by landowners, of both Irish and Old English extraction, that they had been harshly and avariciously dispossessed. Many of those who seem to have dispossessed them survived as a new elite beyond the war and upheaval that erupted in Ireland after 1641. The Book of Survey and Distribution covering Wexford (which also covers Kildare) does give a strange sense of who the winners ultimately were in Wexford. In the barony of Gorey, for instance, the list of individuals confirmed in various landholdings by 1668 under the Acts of Settlement and Explanation (which had adjusted and regularized the new dispensation) includes the names of landowners and landholders who had been present in the region since the early years of the plantation in the county, such as the Masterson and Sinnott families, Dudley Colclough, or the earl of Anglesey (who enriched himself enormously in these years).

Books of Survey and Distribution: Vol 2. County Wexford and County Kildare. Entry for the Barony of Gorey (RIA MS G iii 2)

And this is what gives the Books of Survey and Distribution a claim to be considered among the most important documents in modern Irish history. Their neat and accurate tabulations of who owned how much land, and where, starkly reveals the foundation on which the power and influence of the new ruling elite of seventeenth-century Ireland came to rest. The revolution in Irish land ownership that took place between 1640 and 1670 was the most dramatic social transformation to take place in Ireland between the Flight of the Earls in 1607 and the Great Famine of the 1840s. It effectively shaped the balance of social, economic and political power on the island for the next two centuries. The copies of the Books of Survey and Distribution held in the RIA illustrate how that balance of power stood at the end of the 1660s, and how it had changed since the outbreak of war in 1641.

Dr John Gibney

Assistant Editor with the Royal Irish Academy's Documents on Irish Foreign Policy series.

Sources and further reading:

Kevin Whelan (ed), Wexford: history and society (Dublin, 1987).

Trinity College Dublin Down Survey website: http://downsurvey.tcd.ie/