Bringing the Stowe Missal to life

22 May 2020This month's Library Blog post looks at the Stowe Missal. Thank you to our guest writer Lars Nooij for bringing this wonderful manuscript to life.

There is a certain joy to be had in studying an ancient manuscript and slowly uncovering some of its history. Early medieval scribes rarely left a note saying when, where and why they wrote what they did, but it is often possible to get at least something of an answer to such questions simply by looking at what traces and hints they left behind through their actual use of a text. For whether it’s scribbling notes in the margin, adding in entirely new pages, or even just doodling, medieval users often altered manuscripts to suit their needs and in so doing unintentionally told us something of themselves.

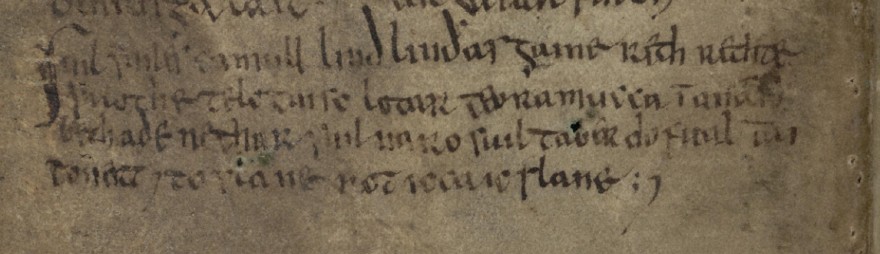

For the past four years, I have been looking into the history of the Stowe Missal (RIA MS D ii 3, Cat. No. 1238). The manuscript is truly a humble production, measuring only some 15x12 cm and being but sparsely decorated, but it must have served its purpose all the same back when it was made in the early ninth century. That purpose seems to have been to provide an itinerant priest with the texts he needed to say Mass, as well perform such sacraments as Baptism and the Anointing of the Sick. And in light of three healing charms in the Irish language on the final page of the manuscript, which appear to have been added over an extended period of time by the same scribe that wrote the Latin main parts of the text, it would seem that the original scribe of the Stowe Missal was also its first intended user.

Third charm, RIA, MS D ii 3, f. 67v

To my mind, little stories such as these bring life to a text, putting us just that bit closer to an otherwise unknowable past. Of course, knowing something of a manuscript’s users also helps us in an academic sense, allowing us to better contextualise whatever other facts we might glean from a text.

Over the last few weeks, I have been sharing various aspects of the history of the Stowe Missal over on Twitter in an ongoing series called Tweeting the #StoweMissal, which will last through to the end of May. The present health crisis has obviously disrupted much of academic life, but I am glad to say that at least some of it has been able to continue online. It has truly been delightful to see scholars from various fields offer questions and suggestions whenever something struck their interest.

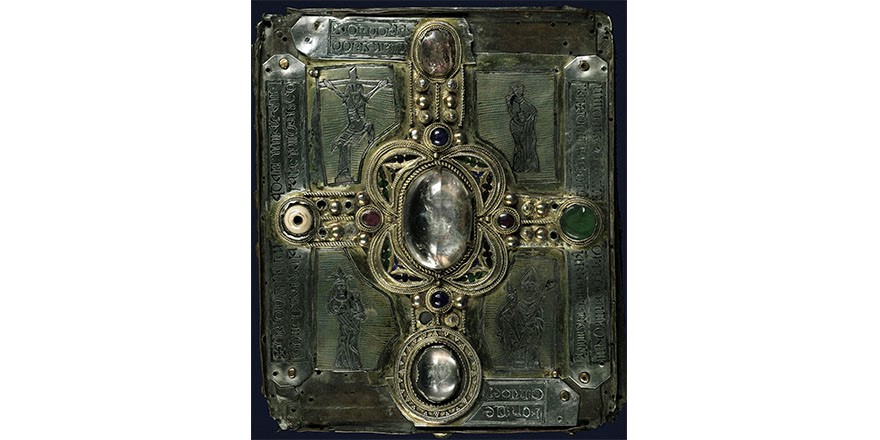

When we began in early May, we first set out the basic facts on the manuscript, although admittedly there is little consensus on any aspect of the Stowe Missal’s history (or even its name, for that matter!) beyond its physical dimensions. Since then, we have ventured deep into the fraught matter of when and where the manuscript was created, travelling from the early ninth century Céli Dé (or: Culdee) monastery of Tallaght to the Tipperary monasteries of Terryglass and Lorrha. Along the way, we investigated the bookshrine in which the manuscript was preserved as a holy relic throughout the later medieval and into the early modern period. We even went on a virtual trip to the Continent to look at some manuscripts which appear to be products of the same scriptorium as the Stowe Missal.

The Shrine of the Stowe Missal, upper face. This image is reproduced with the kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland.

At the time of writing, we have left the medieval period behind us and are discussing the complex series of events, involving various 18th and 19th century Irish and British aristocrats, by means of which the Stowe Missal eventually came to be held by the Royal Irish Academy. The manuscript, of course, remains at the Royal Irish Academy to this day and although we may not be able to physically access it at the moment, we are fortunately still able to view the manuscript online by means of the freely accessible scans of its pages on the Irish Script on Screen website.

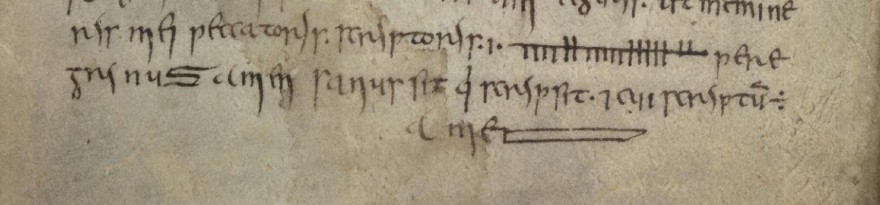

Should this blog have sparked your interest, you are of course more than welcome to join us over on Twitter, where daily discussions continue to be posted. To end with a medieval flourish, which seems particularly apt at this time, quoting the scribe who signed off in ogam as Sonid on the Stowe Missal’s fo. 11r:

Amen. Sanus sit qui scripsit et cui scriptum est. Amen.

“Amen. May he who has written and the one for whom it has been written [i.e. in this instance you, the reader] be healthy. Amen.”

Scribal colophon, RIA, MS D ii 3, f.11r

The present work was undertaken as part of the research project Chronologicon Hibernicum (ChronHib). The research on ChronHib has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 647351).

Lars B. Nooij

PhD student

Department of Early Irish Studies

Maynooth University

For Dublin Festival of History, 2020, Lars gave an illustrated talk on the the Stowe Missal and it's possible connection to Tallaght. Watch here: https://www.ria.ie/made-tallaght-investigation-origins-early-medieval-irish-manuscript-known-stowe-missal

Further Reading:

Lars B. Nooij, “The Irish Material in the Stowe Missal Revisited”, Peritia 29 (2018) 101-110.