DIB Rogues: William Burke, murderer

15 June 2020The DIB has curated a selection of its most notorious rogues – pirates, blackmailers, thieves and murderers – for your delectation. Next in our catalogue of crime is the infamous William Burke, who turned to murder to earn a lucrative fee providing dead bodies to early nineteenth-century anatomists.

William Burke

by James Quinn

Burke, William (1793?–1829), murderer, was born probably at Urney, near Strabane, Co. Tyrone, son of Neil Burke, labourer. Born into a catholic, Irish-speaking family, he received some education and was servant to a presbyterian minister for a time. When he tired of this he tried the trades of baker and weaver, and served in the Donegal militia (c.1809–15) with the rank of private, as a manservant and a bandsman; apparently he was an excellent flautist. During this time he married Margaret Coleman of Ballina; they had two children. After leaving the army he again worked as a domestic servant and an agricultural labourer. In 1818, after a dispute over land with his father-in-law, he left and went to Scotland, where he found work as a labourer on the Union Canal linking the Forth and Clyde Canal to Edinburgh at Maddiston. Here he began to cohabit with a Scottish woman, Helen McDougal. After the canal works were finished (August 1822) he spent another two years labouring at Peebles, before drifting into Edinburgh where he earned a living as a cobbler. Late in 1826 Burke and McDougal moved to West Port, Edinburgh; there they met (c. September 1827) Margaret Hare, who suggested they move in to her lodging house in Tanner's Close, where there was a cellar where Burke could work. Margaret, an Ulsterwoman, was the wife of William Hare (fl. 1792–1829), an illiterate catholic labourer, a native of either Newry or Derry, who had also come to Scotland c.1819/20 to work on the Union Canal. After the canal work finished in 1822 Hare worked as a casual labourer, hawker, and boatman at Port Hopetoun, Edinburgh. He married Margaret Laird in 1826 after the death of her first husband, James Logue (or Log, or Laird), and helped her run the lodging house, living off its earnings.

On 29 November 1827 an old man named Donald died at Hare's lodging house. He owed the Hares £4 in rent, and Hare suggested that they should recoup their loss by selling his body for dissection. Since usually only the corpses of hanged murderers were given to anatomists, there was a strong demand for more bodies. Burke agreed and the following day they sold the corpse to Dr Robert Knox, an Edinburgh surgeon, for £7. 10s. No questions were asked about its origins, and Knox's assistants gave the impression that further corpses would be welcome. According to Burke, Hare then suggested that they could meet this demand by luring poor travellers into the lodging-house and killing them. Over the next year they killed about sixteen people (eleven at Hare's lodging house and about five in other places). Most of the victims were old and frail, but they also included a boy of 12; often they were widows and vagrants – people without close family ties, whose disappearances would go unnoticed. The killers usually plied their victims with drink and then suffocated them by placing a hand over the mouth and nose, so that there were no signs of violence on the bodies. They then sold the corpses to Dr Knox's school of anatomy for payments of £8 to £14. Despite their traditional reputation, there is no evidence that they ever engaged in grave-robbing.

On one occasion each, they acted separately and did the killing on their own, but in October 1828 they were cooperating again and around the middle of the month they killed a mentally challenged 19-year-old, ‘Daft Jamie’ Wilson. On 31 October 1828 they suffocated an old woman, Mary (Margery) Docherty, in Burke's house. Some of Burke's lodgers became suspicious and after a brief search found Docherty's dead body under a pile of straw. They contacted the police, who arrested Burke and Helen MacDougal on 1 November. The Hares were arrested the day after, and maintained that Burke was the instigator of the murders. The authorities, perhaps seeing them as the more pliable witnesses, persuaded them to turn king's evidence. Hare confessed on 1 December, but his confession has disappeared. Burke and McDougal were tried only on two counts of murder at Edinburgh on 24 December, as the authorities were anxious to conceal the scale of their murders. Burke was convicted and sentenced to death, while the case against McDougal was not proven.

Burke made two confessions in jail, an official one on 3 January 1829 and another to the Edinburgh Evening Courant (21 January). He tried to clear all who came under suspicion except Hare, who, he maintained, was still capable of murder. Burke, who went calmly to his death, was hanged at 8.15 a.m. on 28 January in Edinburgh before a crowd of about 20,000 who cried ‘Burke him! Give him no rope!’ (Thus ‘burke’ became another word for suffocate or strangle.) His body was given to anatomists and publicly dissected before an excited crowd by Knox's rival, Alexander Monro, professor of anatomy at Edinburgh University; Burke's skeleton was later displayed in Edinburgh University's anatomical museum. Burke exonerated Knox from all blame, but the anatomist was widely condemned and became the subject of many ribald verses: ‘Burke's the butcher, Hare's the thief/Knox the boy that buys the beef’ (Roughhead, 18).

Burke was described as ‘peaceable’ when sober and ‘even when intoxicated, rather jocose and quizzical’ (Edwards, 295). He occasionally read the Bible, enjoyed music, and was friendly and affectionate towards local children. More affable and plausible than Hare, he tended to win the confidence of victims and then lure them back to the lodging house. His quiet, friendly personality made a reasonably good impression on jailers and magistrates, but nobody took to Hare, who was an embittered and quarrelsome man. Rigorously cross-examined at Burke's trial, he carefully managed to avoid incriminating himself. Many contemporary observers, including Sir Walter Scott, thought that Burke had been made a scapegoat, and at Burke's hanging the mob had shouted for Hare to suffer the same fate. In January 1829 the family of ‘Daft Jamie’ attempted to indict Hare for his murder, but the prosecution was quashed by the high court (2 February) on the urging of the lord advocate. Hare was released on 5 February, and set out for Dumfries, where he was almost lynched by a mob. On 7 February he was spotted near Carlisle. For many years afterwards there were numerous reported sightings of him in various places, but none of these have been authenticated. Margaret Hare, like her husband, was lucky to escape without punishment. She had lured victims to the lodging house, taken £1 for each body for the use of her house, and had helped pack the bodies in boxes. She, too, was attacked by mobs after her release, and in February was escorted to Greenock and sailed for Belfast. Helen McDougal was believed to have moved to England. After February 1829 all three of Burke's accomplices disappear from the historical record.

The actions of Burke and Hare contributed to the passing of the anatomy act (1832) which regulated the procuring of corpses for dissection.

Sources: Anon., West Port murders (1829) (portrs); George MacGregor, The history of Burke and Hare (1884); James Grant, Cassell's old and new Edinburgh (3 vols, 1884–6), ii, 226–30; James Moore Ball, The sack-em-up men (1928); William Roughhead (ed.), Burke and Hare (1948) (portrs); Hugh Douglas, Burke and Hare: the true story (1973); Owen Dudley Edwards, Burke & Hare (1980)

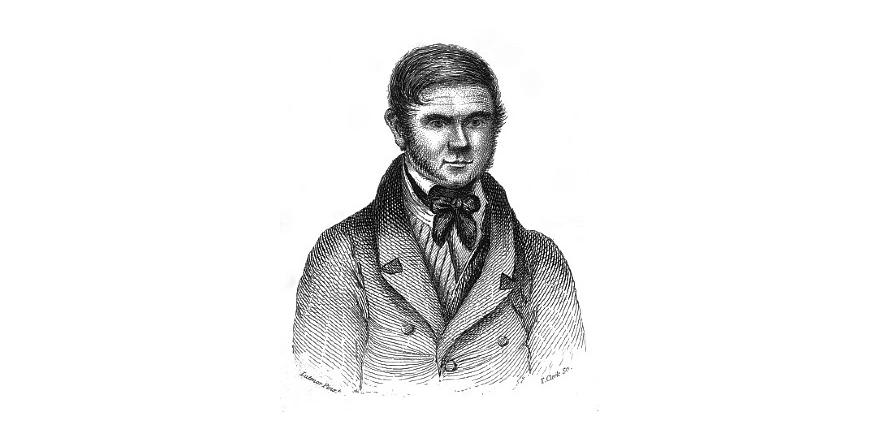

Image: ‘William Burke as he appeared at the bar. Taken in Court’ found in Anon, West Port Murders, or An Authentic Account of the Atrocious Murders Committed by Burke and His Associates (1829)