The DIB and 'Renaissance Galway'

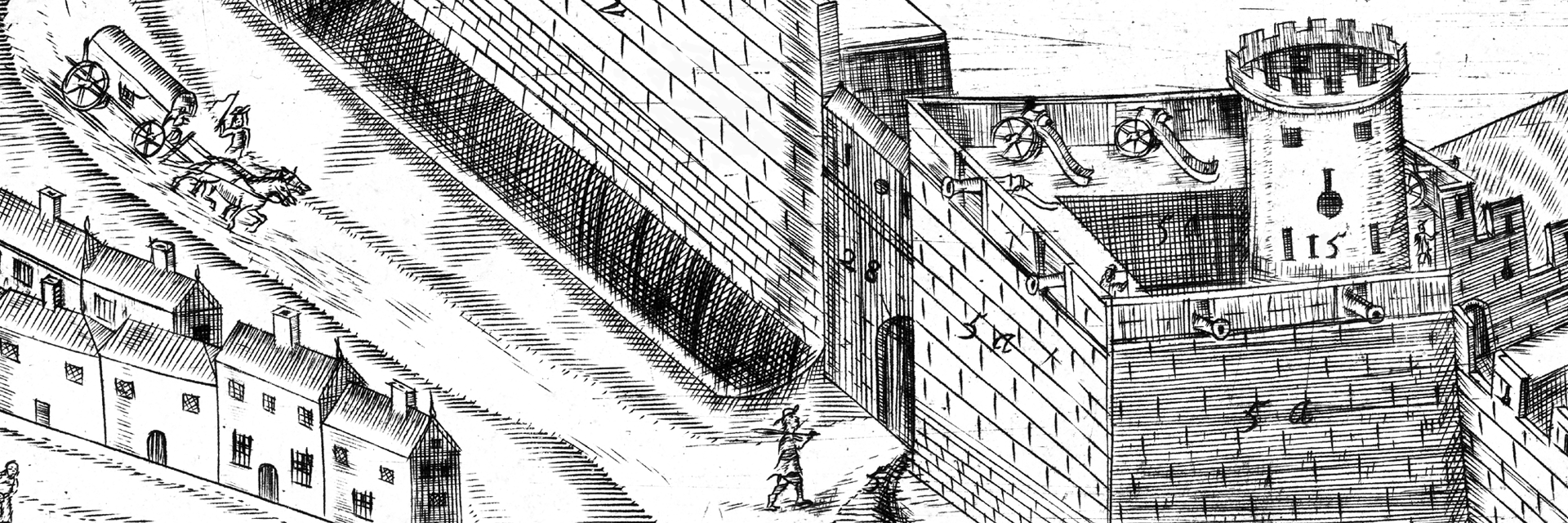

15 October 2019To celebrate the publication of Renaissance Galway: delineating the seventeenth-century city by Paul Walsh, we publish the DIB entry on Walter Lynch, by Terry Clavin, below. A vicar of St Nicholas's collegiate church, following his appointment as bishop of Clonfert in 1647 Lynch was active in the politics of the period.

Walter Lynch (1593?–1663), catholic bishop of Clonfert, was the son of James Lynch, a merchant of Galway city, and his wife, Appollonia. He was educated first in Galway and then at the Irish college at Lisbon, where he studied philosophy. On returning to Ireland, he acted as a schoolmaster and founded schools at Gort, Co. Galway, and at Limerick, before travelling to Paris, where he studied theology, eventually receiving a doctorate in divinity. About this time he was probably ordained a priest, and he returned to Ireland to become warden of Galway. This was a prestigious position and the holder enjoyed quasi-episcopal jurisdiction in Galway city. Lynch was reelected to the position many times, which was unusual. He resigned as warden to study civil law at Orleans in France, and about 1631 he became a doctor of civil law. As such, he was highly regarded when he resumed his post as warden and was frequently called on to arbitrate in legal disputes and other disagreements. He had a large collection of books and was noted for his abstemious lifestyle. Despite being obliged to celebrate mass in a cramped oratory, he had organs installed for the edification of those present. By 1642 he was protonotary apostolic and dean of Tuam.

Following the outbreak of rebellion in October 1641, the mainly catholic populace of Galway favoured rising against the crown. The town council, also mainly catholic, equivocated, concerned by the presence of a protestant garrison at the fort of St Anthony's overlooking the city. The clergy, led by Lynch, urged the council to declare for the rebels and to attack the fort. In March 1642, at Lynch's instigation, the catholic leaders of Galway swore an oath of mutual union and defence, which effectively brought the town into rebellion. However, many of the aldermen and burghers continued to have second thoughts, particularly as the garrison at St Anthony's began shelling the city. Hence on 8 May 1642 the city council agreed to submit to the king on terms. The next day, a furious Lynch excommunicated those who had voted for submission. In the event, the terms of the submission were disowned both by the Dublin government and by the English parliament, and hostilities were resumed. The fort eventually fell to the catholics in 1643 and represented a vindication of Lynch's bellicosity. For the first time, he could claim St Nicholas's church, which was the principal church of Galway and under the care of the warden. He also began to play a wider role in the catholic confederacy of Ireland, travelling frequently to Kilkenny, the confederate capital, and beyond.

Following the death of Malachy O'Queely (qv), archbishop of Tuam, he acted as vicar-general of Tuam in 1646. On 12 August 1646 he signed the decree of the ecclesiastical congregation at Waterford condemning the supreme council of the confederacy's alliance with James Butler (qv), marquess of Ormond and royalist governor of Ireland. En route to Galway, Lynch heard that Ormond had sent two of his men to proclaim the alliance in Limerick. He hastened to the city, where he publicised the excommunication by GianBattista Rinuccini (qv), papal nuncio to Ireland, of those who adhered to the alliance. The city council decided to proclaim the alliance regardless, prompting a massive riot by the populace. The two men sent by Ormond were chased out of Limerick.

Hugely impressed with Lynch and regarding him as foremost among his peers, Rinuccini arranged his appointment to the bishopric of Clonfert on 1 March 1647 (O.S.). His consecration occurred at Waterford on 9 April 1648. The supreme council had recommended someone else for Clonfert and resented the nuncio's interference in the matter. Lynch amply proved his worth to Rinuccini during the controversy that surrounded the nuncio's excommunication in May 1648 of those who adhered to the supreme council's cessation with the protestant forces in Munster. Following the pronouncement of the excommunication, Rinuccini and his supporters set out for Galway. Lynch travelled ahead and, on arrival, suspended two prominent local priests for opposing the censures and preached that the cessation was designed to bring about the destruction of the church. In September he wrote to Rome asking the pope to make Rinuccini cardinal of Ireland. Nonetheless, by the year's end, the supreme council clearly had the upper hand. In early 1649 Rinuccini left Ireland and the supreme council finally realised its alliance with Ormond.

However, this alliance proved incapable of resisting the English parliament's invasion of Ireland. In August 1650 a clerical congregation at Jamestown excommunicated Ormond's supporters and sent Lynch and the bishop of Cork to demand Ormond's resignation. When Ormond procrastinated, Lynch tried to get the catholic officers in the royalist army to sign a recantation of their opposition to Rinuccini. In November 1650 Ormond called another congregation at Lough Rea, packed with his own supporters, in order to reverse the Jamestown excommunication. Lynch was in attendance, but he walked out when pressure was brought to bear on the bishops to declare that they could not release subjects from obedience to a governor appointed by their king. Overall, he played a pivotal role in the factional in-fighting among the catholics during 1649–52 because he acted as secretary to a series of clerical congregations held in this period. He was also heavily involved in efforts to have the duke of Lorraine made protector of Ireland.

After the fall of Galway city in April 1652, Lynch fled to Inishboffin, which held out until February 1653. Faced with the options of exile or death, he chose the former and sailed into Ostend with other refugees on 26 April, before journeying to Brussels. He was still there in April 1654, vainly awaiting some form of preferment. Eventually, in 1655, he made his way to Gyor in Hungary, upon the invitation of the bishop of Gyor. There he acted as canon of the cathedral church and auxiliary bishop. In 1663 he prepared to return to Ireland in order to overcome opposition to his appointment of Daniel Kelly as vicar-general of Clonfert, but he died on 14 July. He was buried in Gyor cathedral.

On arriving in Gyor, he had brought with him a painting of the Virgin Mary with Child, which was hung in Gyor cathedral after his death. It is recorded in a manuscript account still surviving that, on St Patrick's day 1697, the picture of the Virgin Mary began weeping blood in front of a large crowd of onlookers of various denominations. Known as the Consolatrix afflictorum, the painting became the object of widespread veneration in Hungary, but was unknown in Ireland until the close of the nineteenth century.

William Maziere Brady, The episcopal succession (1876–7), ii, 162, 216–17; Gilbert, Contemp. hist., 1641–52, i, 697–9; ii, 116–17, 165; iii, 30–31, 73, 143–4, 276, 300–02; C. P. Meehan, The portrait of a pious bishop(1884), 5–15; Gilbert, Ir. confed., vi, 71, 375; vii, 93–4; J. J. Ryan, ‘Our Lady of Gyor and Bishop Walter Lynch’, IER, 4th ser., i (Jan.–June 1897), 193–205; James Hardiman, The history of Galway (1926), 114; M. J. Hynes, The mission of Rinuccini (1932), 161–2, 183, 216, 230, 236, 277–8, 283, 285–6, 303; Brendan Jennings, ‘Irish names in the Malines ordination register’, IER, 5th ser., lxxvii (Jan.–June 1952), 63–75; Thomas L. Coonan, The Irish catholic confederacy (1954), 309–10; Cathaldus Giblin, ‘The Processus Datariae and the appointment of Irish bishops’, Father Luke Wadding commemorative volume (1957), 508–616; Cathaldus Giblin, ‘Catalogue of material of Irish interest in the Collection Nunziatura di Fiandra’ in Collect. Hib., i (1958), 1–126; Donal F. Cregan, ‘The social and cultural background of a counter-reformation episcopate, 1618–1660’, Art Cosgrove and Donal McCartney, Studies in Irish history presented to R. Dudley Edwards (1979), 85–117; John Lowe, Letter book of the earl of Clanricard (1983), 377; M. D. O'Sullivan, Old Galway (1983), 237, 240, 244, 248, 269; James Mitchell, ‘Fiction and the empty frame’ in Galway Arch. Soc. Jn., xl (1985–6), 20–48

© 2019 Cambridge University Press and Royal Irish Academy. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Learn more about DIB copyright and permissions.

Published by the Royal Irish Academy, Renaissance Galway was launched by Councillor Denis Lyons, Deputy-Mayor of the City of Galway in Galway City Museum on Thursday 10 October 2019. Speakers included Professor Jane Conroy, Vice President for Research, Royal Irish Academy; Jacinta Prunty, Honorary Editor, Irish Historic Towns Atlas and Maynooth University and was hosted by Eithne Verling and the Galway City Museum. A range of other events have marked the publication, detailed here.