Alcohol in the DIB: Theobald Mathew

19 October 2020We continue our series on alcohol in the DIB with famed temperance crusader Theobald Mathew.

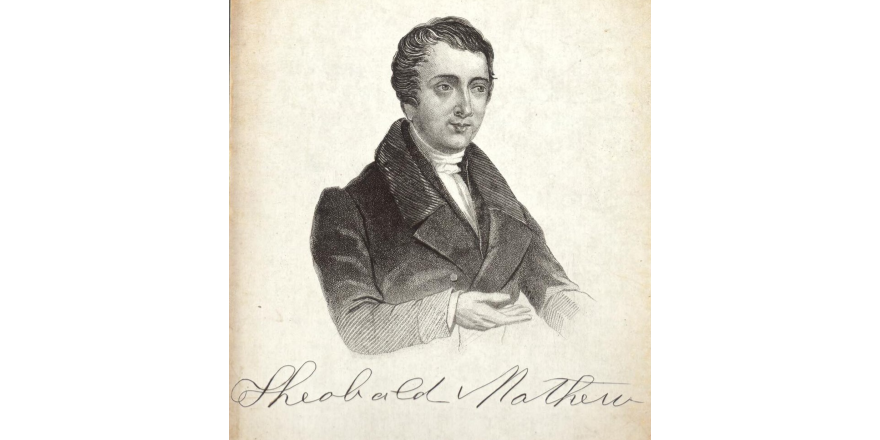

Theobald Mathew

by Thomas O'Connor

Mathew, Theobald (1790–1856), Capuchin priest and temperance crusader, was born 10 October 1790 in Thomastown, Co. Tipperary, fourth of twelve children. His father, James Mathew, who was related to the Butlers, acted as agent for the Irish estates of his protestant cousin, Francis Mathew, 1st earl of Llandaff. His mother was Anne Whyte, daughter of George Whyte of Cappawhite. Mathew's early education was probably at home; he later attended a school run by a man called Flynn in the Market House in Thurles. A local catholic priest, Denis O'Donnell, gave further instruction. Lord Llandaff's daughter, Lady Elizabeth Mathew (d. 1842), took an interest in him. At her expense he was sent to St Canice's Academy, Kilkenny, then run by Patrick McGrath. In 1807 he matriculated in the humanity class of Maynooth College but, consequent on a minor infringement of college discipline, left the seminary. In 1808 he was accepted by the Capuchins in Church St., Dublin, and was ordained priest in 1813 by Daniel Murray.

He spent the first months of his ministry in the friary in Kilkenny but, having fallen out of favour with the local secular clergy, he requested a transfer. He was then assigned to the friary in Blackmoor Lane, Cork city. He was never a gifted orator; his fame as a gentle confessor, however, drew large numbers of penitents not only from the city but from the surrounding countryside, a circumstance that obliged him to learn Irish. He opened a school for girls beside the friary and arranged for the Josephian Society, which he founded in 1819, to run a night school for boys. In 1822 he was made Capuchin provincial, a position he held for nearly thirty years. His relations with the secular clergy were cordial. He was active in obtaining a suitable burial ground for catholics in the city and distinguished himself pastorally during the cholera epidemic of 1832. In the same year he presided at the laying of the foundation stone of the new Capuchin church of the Holy Trinity.

In the 1820s public concern over the abuse of alcohol had grown. Inspired mainly by American models, temperance movements had started in Ireland. Early temperance movements were more usual in dissenting or anglican communities and encouraged moderation in alcohol consumption, rather than complete abstention. By 1834 there were six temperance societies in Cork, all non-catholic. From the early 1830s the ineffectiveness of moderation as a response to alcohol abuse had proved so telling that a policy of total abstinence was adopted by some temperance societies. In 1836 one such movement was founded in Dublin. On spreading to Cork the total abstinence movement was opposed as a foreign practice, hostile to traditional habits of hospitality. Local brewers, long-time supporters of moderation, were not attracted by the new strictness; local distillers opposed it outright. Further, the movement suffered from lack of support among catholics, lay and clerical alike. There were, however, some lay catholics in the movement in Cork and they approached Mathew to solicit his support. Initially he held back, probably because of the unpopularity of total abstinence in the catholic community and because of his own family connections with distillers. In 1838, after much agonising, he consented to act as president of the Cork Total Abstinence Society.

From the beginning, his activity was pointedly non-political and he won considerable support among non-catholics. The pledge administered by Mathew ran: ‘I promise with the divine assistance, as long as I continue a member of the teetotal temperance society, to abstain from all intoxicating drinks, except for medicinal or sacramental purposes, and to prevent as much as possible, by advice and example, drunkenness in others.’ Where crowds were very large, other priests helped Mathew administer the pledge. Once pledged, teetotallers were asked to give their names to their priests, who were then to arrange to have certificates and medals sent on. From Cork, the movement spread to Limerick and Waterford, later to Connacht, Leinster, and even Ulster, although Mathew did not enter Belfast, then in the thrall of Henry Cooke, ‘the presbyterian pope’. His crusade rapidly developed into a mass movement whose organisation, given its scale, was necessarily loose. For this reason, it never became a structured, national organisation. This may be how Father Mathew preferred things, partly, perhaps, out of a fear of losing control, partly out of the conviction that the movement was divinely directed.

Inevitably, after the initial enthusiasm, many new recruits fell by the wayside. This was due partly to bad organisation and partly to the lack of a set of social practices and pastimes that might substitute for those associated with the consumption of alcohol. Regular meetings, reading rooms, rallies, marching bands, and political activity did go some way to filling the gap. Apart from the organisational difficulties and debts incurred by the manufacture and distribution of temperance certificates and medals, there was also the widespread popular belief that taking the pledge from Father Mathew was more effective than taking it from local clergymen. Mathew often had to correct the notion that he possessed miraculous powers.

As might be expected, Mathew experienced significant opposition from extreme protestants who taxed his efforts with superstition and political subterfuge. Opposition also came from Archbishop John MacHale of Tuam, who objected to Mathew's easy movement between dioceses and the freedom he enjoyed in virtue of his official status as commissary apostolic. MacHale also objected to his reputed indulgence towards protestants and his failure to support financially and morally the archbishop's primary schools. Some nationalists found his acceptance of a government pension objectionable. This may explain why in spite of the support of the diocese's parish priests he was not appointed to the see of Cork after the death of Bishop John Murphy in 1847. There was also controversy over the nature of the pledge he administered. While some argued that it was temporary, others believed it permanently binding. Some interpreted it as a mere resolution; others saw it as a solemn vow with specific religious connotations whose breach was subject to divine sanction. Controversy also raged over the alleged administration of the oath to children. Naturally, there was opposition too from distillers and public-house owners who suffered from the decrease in the consumption of alcohol.

On a political level, there was a tendency for the movement to become associated not just with rational self- and social improvement but also with national self-esteem. Some tory newspapers, such as the Limerick Standard and the Dublin Evening Mail, were hostile to the movement. They were especially suspicious of its ability to mobilise the public, and feared it would be used to weaken English rule in Ireland. Conservative observers were especially vocal on the movement's alleged links with O'Connell's fledgling repeal campaign. In late 1840 O'Connell himself took the pledge and persevered for about a year and a half. While it would have been difficult for O'Connell not to take advantage of the temperance movement for his repeal campaign, he did so without Mathew's approval. This is not surprising. Mathew's background was Anglo-Irish; he had numerous protestant relatives, and was nervous of all political involvement that might challenge the status quo. His opposition to agrarian unrest was well known and if he had any political convictions they were those of a paternalistic conservative who believed in order and hierarchy.

By the early 1840s the movement had probably reached its maximum audience, except in Ulster. Many contemporary commentators noted improvement in public order and prosperity, which they attributed to temperance. The rise of repeal agitation probably distracted public concern from the temperance question and already by 1843 the movement was suffering from Mathew's inability to revisit regularly those areas where the campaign had first begun. In 1842–3 he travelled to Scotland and England, where up to 200,000 may have taken the pledge. Affiliation was always loose but by the mid-1840s it was evident that the movement was not sustaining its initial impetus. The famine dealt it a near fatal blow, for it was precisely those counties where the temperance movement had been strongest that the famine hit hardest. Depressingly for Father Mathew, consumption of alcohol grew even as population declined. If he was disappointed, this did nothing to blunt his pastoral concern. He was directly involved in famine relief. Always a valuable source of information for the government, he was tireless in his criticism of profiteers and active in fund-raising for the needy. For a time, when he was a member of the relief committee for Cork city, his own home was transformed into a soup kitchen. In spring 1848 Mathew suffered a stroke. The following year, having made a partial recovery, he travelled to the USA, visiting twenty-five states, where over 600,000 were reported to have taken the pledge. His American crusade suffered from his reluctance to support abolitionism publicly. At this time, his absence from Ireland further weakened a movement already in difficulty, and the American interlude may explain why the temperance issue made little impact on episcopal deliberations at the 1850 synod of Thurles. In 1851 he was back in Cork. At this stage the weakening of the temperance movement, expressed by the growing numbers of backsliders, discouraged him. He died on 8 December 1856 and was buried in St Joseph's cemetery, Cork. Several monuments were raised to him, and his was a potent memory for the later, more highly organised and catholic-dominated Pioneer Total Abstinence Association of the Sacred Heart.

Sources: John Francis Maguire, Father Mathew: a biography (1864); Frank Mathew, Father Mathew: his life and times (1890); Patrick Rogers, Father Mathew, apostle of temperance (1945); Moira Lysaght, Fr Theobald Mathew OFM Cap.: the apostle of temperance (1983); Colm Kerrigan, Fr Mathew and the Irish temperance movement 1838–1849 (1992); Diarmaid Ferriter, A nation of extremes: the Pioneers in twentieth-century Ireland (1999)

Image: A portrait of Theobald Mathew from the Welsh Portrait Collection at the National Library of Wales. Artist unknown.