Alice Kyteler: Ireland's first witch

30 October 2019To mark Samhain we present the biography of Alice Kyteler, the first recorded person to be condemned for sorcery in Ireland.

by Ronan Mackay

Kyteler (Kettle, Keyetler), Dame Alice (fl. 1324), accused of witchcraft and sorcery, was probably from a Kilkenny family, though nothing is known of her life prior to marriage. The Kytelers were a family of Flemish merchants who came to Ireland some time in the mid to late thirteenth century and may have settled in Flemingstown, Co. Kilkenny. Between 1280 and 1285 Alice seems to have married her first husband, William Outlaw, a successful moneylender and merchant of Kilkenny, and probably brother of Roger Outlaw, the future prior of the hospital of St John of Jerusalem. When William died, his son with Alice, William Outlaw (Utlagh) (see below), took over the business. By 1303 Dame Alice had married a second time, to Adam le Blund of Callan, who also seems to have been a very wealthy man, and by 1309 she had married her third husband, Richard de Valle, of a prominent family in Co. Tipperary. Between 1316 and 1324 she married her fourth husband, Sir John le Poer. Her acrimonious relationship with her stepchildren was the genesis of all her problems. It seems she succeeded in persuading some of her husbands to disinherit their children in favour of the son of her first marriage, William Outlaw. So, for example, in 1307 Adam le Blund quitclaimed all of his goods to Outlaw. Her rights of dower – ownership of one-third of her husbands’ estates following their deaths – also brought her into conflict with her stepchildren and their families, and she was forced to go to court on more than one occasion to secure these rights.

By 1324, therefore, she had acquired a substantial fortune and a large landed interest. She also used her capital to engage in money-lending, which led to further animosity towards her. As early as 1302 she had been accused (and acquitted) of murder and other crimes. Evidently her stepchildren, lacking the evidence of a natural crime, suspicious of their fathers’ deaths, and bitter over their loss of income, became convinced that she had access to supernatural powers and had used these powers first to beguile, and then to dispose of, her husbands. They couched these suspicions in the popular terminology of the time – maleficium (the ability to harm one's neighbours through occult powers supplied by the devil). They approached the zealous Franciscan bishop of Ossory, Richard Ledrede, with their suspicions early in 1324. Ledrede summoned an inquiry, and the witnesses – many from the local community, no doubt some in debt to Kyteler and her son; the rest, her stepchildren and their families – accused her and William of being sorcerers and heretics. Ten others, men and women, were included as their accomplices in terrible crimes, which went beyond simple maleficium. It was asserted that this group, headed by Kyteler, concocted powders and potions made from all sorts of vile ingredients, which – mixed in the skull of a decapitated robber, surrounded by candles made from human fat, and accompanied with horrible incantations – brought illness or death to innocent Christians. Indeed, it was reported that Kyteler's last husband, who died early in 1324 from a wasting illness, having been warned of his wife's activities by a maid, had discovered many of these ingredients in her chests and forwarded them to Ledrede. In order to make their spells and potions even more effective, all the members of this circle were alleged to have renounced Christianity and, going further, to have sought the aid of demons, to whom they sacrificed animals. Dame Alice was said to have had a private demon, her incubus, with whom she had sexual relations. Through him she gained her unheard-of wealth.

After the inquisition Petronilla of Meath was flogged on the bishop's orders, and ‘publicly’ confirmed that each of the charges made at the inquiry was true. She had seen Kyteler's demon lover with her own eyes. With such evidence at his disposal, Ledrede wrote to the chancellor of Ireland, Roger Outlaw, and demanded that all of Kyteler's associates be arrested. Outlaw refused and Ledrede was forced to act on his own authority. He summoned Alice to appear before him, but she fled from Kilkenny to Dublin, where she may have found refuge with Roger Outlaw. Next he charged William Outlaw with heresy, but before he was due to attend the hearing, Arnold le Poer, the seneschal of Kilkenny, intervened. Le Poer, a relation of Dame Alice's fourth husband, whose support may have been bought by Outlaw, went with Outlaw to the bishop's residence to try and reason with Ledrede. When this failed, le Poer threatened him and then had the bishop arrested and imprisoned in Kilkenny jail till the day for which Outlaw had been summoned had passed. Undeterred, Ledrede again summoned Outlaw to appear before him, excommunicated Alice, and placed his entire diocese under interdict. She in turn sued the bishop for defamation of character, and Arnold le Poer – probably with another of her allies, Walter Islip, the treasurer – caused him to be summoned before the parliament at Dublin in May 1324. There the bishop pleaded his case with persuasive eloquence against Alice, William Outlaw, and Arnold le Poer. By July the justiciar, John Darcy, had ordered the arrest of Alice and her son. Shortly afterwards Darcy went to Kilkenny to aid Ledrede. In front of the king's Irish council and several lay and ecclesiastical judges, Dame Alice was accused of heresy and sorcery. The arrest of her co-conspirators was also agreed to and Ledrede interrogated some of these, though others were released on the payment of securities. Some of those arrested were publicly flogged, others banished and declared excommunicate, and Petronilla of Meath was later burned alive for her crimes, on 2 November. Ledrede must have been horrified that the chancellor and treasurer, when they accompanied Darcy to Kilkenny, stayed at Outlaw's residence in the city. Kyteler, now convinced nothing more could be done to avoid persecution, fled to England in July with the daughter of Petronilla of Meath and (according to the Anglo-Irish annalist) was never seen nor heard from again.

William Outlaw (d. p.1326), Alice's son, was arrested and imprisoned. He was cited to answer all the charges against him before the justiciar, the chancellor, the treasurer, and Ledrede. At that meeting some sort of compromise was reached. While Ledrede strenuously denied that he had been bought off, Outlaw, in return for his full confession to all of the crimes he was charged with (Ledrede had drawn up a comprehensive list of thirty-four indictments), had his prison sentence commuted to penance. He was to hear mass at least three times daily for one year, feed a particular number of poor of the diocese, and (most expensive of all) pay for the roofing of the cathedral church of St Canice with lead. Ledrede quickly became convinced that Outlaw's submission and penance were insincere and had him cited to appear before his ecclesiastical court once again. Towards the end of October or the beginning of December 1324 William was arrested and imprisoned in Kilkenny castle for two months before another compromise was negotiated on 17 January the following year. William's uncle, Roger, undertook to act as security for William's payment for the roofing of the church; if it was not completed within four years Roger would pay for it himself. Also, Roger Outlaw granted the fruits of two churches to the dean and chapter of St Canice's. This seems to have been commuted for a money payment to the bishop; Roger and ten prominent landholders agreed they owed Ledrede £1,000, which the bishop later acknowledged he had been paid. This money had evidently been guaranteed by William Outlaw, for in August 1326 he acknowledged his debt to Roger of £1,000. Thereafter William disappears from the records, though if he was still alive in 1332 he may have taken some pleasure in the fact that much of the church of St Canice was wrecked when the bell tower – and presumably the lead roof which he had funded – collapsed and destroyed the chancel and sacristy.

Sources:

DNB; Chartul. St. Mary's, ii; Clyn, Annals of Ireland; A narrative of the proceedings against Dame Alice Kyteler for sorcery, A.D. 1324, ed. Thomas Wright, Camden Society, xxiv (1843); Cal. Carew MSS (Book of Howth); G. H. Orpen, Ireland under the Normans, iv (1920); K. M. Lannigan, ‘Richard Ledrede, bishop of Ossory’, Old Kilkenny Review, xv (1963), 23–9; Edmund Colledge (ed.), The Latin poems of Richard Ledrede (1974); Norman Cohn, Europe's inner demons (1975); Robin Frame, English lordship in Ireland 1318–61 (1982); Anne Neary, ‘The origins and character of the Kilkenny witchcraft case of 1324’, RIA Proc., lxxxiii C (1983), 333–50; NHI, ii; J. A. Watt, The church in medieval Ireland (2nd ed., 1998), 260–63; Bernadette Williams (ed. and transl.), The annals of Ireland (2007)

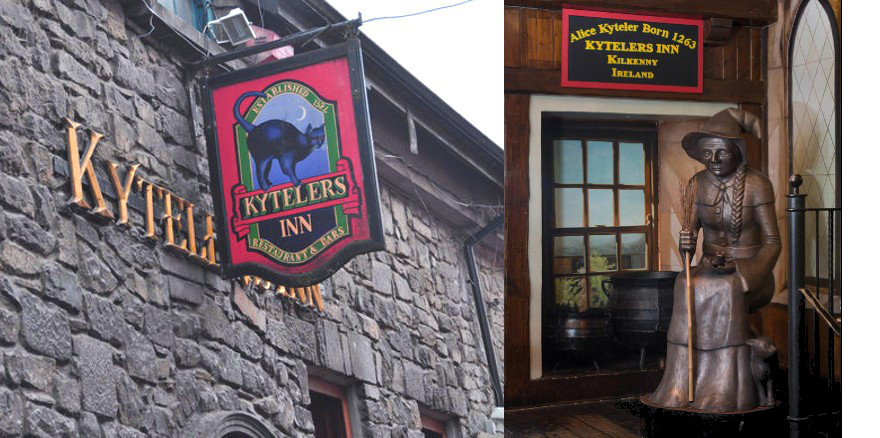

Images: Kyteler’s Inn in Kilkenny, said to have been established by Dame Alice Kyteler in 1324.