Favourite DIB lives: James Deeny, medical doctor and public health official

01 May 2020Selected by the DIB's Turlough O'Riordan, doctor James Deeny was a leading public health figure in Ireland, and internationally, with the World Health Organisation. Widely respected for his scientifically rigorous medical research and his public policy accomplishments, Deeny's career illustrates the global nature of public health.

Introduction by Turlough O'Riordan

The WHO was established in 1948, incorporating remnants of the public health and medical research infrastructure left over from the League of Nations. Tasked with promoting public health in the widest sense, the WHO played a key role in the post-war development of vaccines in pursuit of eradication of communicable diseases – such as small-pox and polio, and more recently, ebola. By directing existing expertise to where it is most needed, and coordinating international research and responses to public health emergencies, the organisation remains central to global public health today.

James Deeny (1906–94), after a stellar medical and scientific education, became a leading public health physician in Ireland. His early researches into malnourishment in Lurgan, Co. Armagh, spurred further work examining vitamin deficiency and the epidemiology of tuberculosis. Appointed chief medical advisor to the Department of Local Government and Public Health in Dublin in 1944, Deeny went on to leave an indelible mark on the Irish health system.

Having represented Ireland at the inaugural WHO assembly in 1948, Deeny undertook surveys of TB in Ceylon, British Somaliland, and later served as chief of mission in Indonesia. His career, based on rigorous medical and scientific research, public service, and participative international cooperation, resonates deeply with contemporary efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

James Deeny

By Lawrence William White and Diarmaid Ferriter

Deeny, James Andrew (1906–94), medical doctor and public health official, was born 7 November 1906 in North Street, Lurgan, Co. Armagh, one of three children of Michael Deeny, doctor, and Jane Margaret Deeny (née Donnelly); his sister Sheelagh and brother Donnell also became doctors. The family eventually moved to Church Place, where his father conducted his large and successful general practice, serving Lurgan and the surrounding countryside, from the family home. A catholic, Deeny received primary education locally before entering Clongowes Wood College, Co. Kildare (1918–23), and studied medicine at QUB (1923–7), graduating with an honours degree. Thereafter he assisted in his father's practice while commuting daily by train to postgraduate studies at QUB; by 1930 he had obtained a B.Sc. in biochemistry, bacteriology, and pathology, a diploma in public health, an MD in pathology, and membership of the RCPI. Despite his brilliant academic record, he was not offered a house surgeon's post at the Royal Victoria Hospital, which he ascribed to the sectarianism that he perceived as prevalent in medicine in Northern Ireland. He worked six months in Vienna researching the bacteriology of tuberculosis in the state serum institute (1930–31).

In September 1931 he opened his own general practice in Lurgan, in premises adjacent to his father's surgery. Conscious that an outmoded Victorian model of clinical practice was still dominant in Irish medicine, Deeny was determined to pursue a more modern approach, based on scientific research into the causes and treatment of disease, and a humane approach to the ill. His experience of general practice among small farmers and town workers, whose long-term poverty was exacerbated by the economic depression, aroused his interest in certain diseases, and in the relationship between illness, poverty, and nutrition. In 1938 he conducted a survey of the nutritional status of male linen-factory workers in Lurgan. His findings, published in the British Medical Journal(February 1939), revealed widespread malnourishment, and illustrated a stark concurrence of malnutrition, low family income, and large families. A companion survey of female linen workers, published in the Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland (May 1940), revealed yet more serious levels of malnutrition. Awarded an M.Sc. by QUB for the research, in 1941 he was elected a fellow of the RCPI, a member of the RIA, and chairman of the mid-Ulster division of the British Medical Association.

In the early 1940s Deeny published several studies of various types of vitamin deficiency, and conducted a survey of infant mortality in Belfast (where one in eight babies died in their first year). He attracted international attention with an article (1943) reporting his successful treatment with liberal doses of vitamin C and sodium bicarbonate of two brothers (‘the blue men of Lurgan’) afflicted with a rare congenital blood condition causing blue-hued skin. During the second world war he became a chemical warfare officer for Lurgan. The health ministry in London sought his advice on nutrition in Northern Ireland, and he broadcast lectures on BBC Belfast emphasising good nutrition on limited budgets. He conducted an epidemiological study of tuberculosis in Lurgan (published in December 1947), examining how the disease spread in a congested urban environment, a process that he termed ‘slow motion contagion’; his findings highlighted the imperative to isolate infectious cases.

His publications having aroused the interest of medical academics in the south, Deeny received research grants from the Medical Research Council, while the Central Statistics Office assisted the processing of his data. In 1944 he was appointed chief medical adviser to the Department of Local Government and Public Health in Dublin. Exerting ‘an electrifying effect on the department, throwing out ideas in a way a generating plant discharges current’ (Barrington, 156), he vigorously addressed the most pressing public health issues. Seeking to translate advancements in medical science into improved and accessible public health services, he began with a scientific and social analysis of each issue, followed by identification of the most effective intervention; the existing public health machinery was then mobilised to implement the intervention, and new structures were designed when needed. Owing to his initiatives, within several years major progress had been made in the control of typhoid fever and louse-borne typhus, in reducing the high rates of maternal and infant mortality, and in confronting an epidemic of infantile enteritis in Dublin. His comprehensive plan to combat tuberculosis was published as a government white paper (January 1946). Outlining a thorough reorganisation of TB services, the plan called for provision of the most modern techniques of diagnosis and treatment in fully equipped sanatoria; services would be free, and a maintenance allowance extended to patients and their families. Deeny's plan laid the foundation for the remarkably successful anti-TB campaign of the ensuing decade. Deeny oversaw a national nutritional survey (1946–8), the first ever conducted in independent Ireland, which concluded that the nation generally was adequately nourished, while identifying vulnerable groups: low-paid workers, the unemployed, widows, and pensioners.

Deeny worked compatibly with the department's parliamentary secretary with responsibility for public health, the Fianna Fáil TD and fellow doctor F. C. Ward, who latterly described Deeny as ‘a genius’, and his recruitment ‘one of the best things that had ever happened to the public service’ (Deeny (1995), 11). Involved in the drafting of all public health legislation of the period, Deeny chaired a departmental committee (1944–5) that formulated radical proposals for a free and comprehensive national health service, funded largely from general taxation, and incorporating virtually all GP, specialist, and hospital services; private medicine would be a minor and peripheral activity. Though endorsed by Ward, the committee's report was never published owing to opposition within government, though one of its major recommendations, establishment of an independent Department of Health, occurred in January 1947. The Deeny committee's proposals, in diluted form, were the basis of a 1947 white paper, which projected the phased introduction of comprehensive services. With free TB services already introduced, the white paper included, as the next phase, a scheme that Deeny christened the mother and child service, assuming that nobody could oppose a free medical service with such a name. The early phases outlined in the white paper were given statutory basis in the 1947 health act.

Deeny had a problematic relationship with Noel Browne, the charismatic but mercurial minister for health in the inter-party government installed in 1948. Browne had ferociously savaged the department's record in combating tuberculosis, and had accused Deeny of ignoring socio-economic factors in the disease's transmission in his published Lurgan study. Asked by Fine Gael leaders whether he could work with Browne, Deeny replied that he would work with Satan himself to eradicate TB. As minister, Browne accelerated implementation of the anti-TB programme, injecting the campaign with a sense of urgency and priority. In this and other arenas, Browne's achievement largely was to implement, with intense conviction, abundant publicity, but scant acknowledgement, the groundwork already prepared by Deeny and his civil servants. After an initial period of collaboration, Deeny clashed with Browne over matters of policy and strategy. Two strong-willed and opinionated individuals, one a reformer, the other a radical, they represented different generations, social backgrounds, professional paths, and political ideologies. Browne regarded Deeny as part of the dilatory state apparatus, and a paternalistic representative of an entrenched professional elite. Deeny was both offended and alarmed by Browne's incapacity for diplomacy and compromise, epitomised by his intemperate public assaults on the integrity of the medical profession.

Deeny was seconded by Browne (who thereby removed him from the making of policy) to the Medical Research Council as director of a national tuberculosis survey (1950–53). He thus was absent from the department when Browne's efforts to implement the mother and child scheme failed amid concerted opposition from the medical profession and the catholic hierarchy. On returning to the department (1953–6), he concentrated on implementing the diluted form of the scheme embodied in Fianna Fáil's 1953 health act, effecting the recommendations of the TB survey, and expanding hospital and specialist services. Having led the Irish delegation to the inaugural assembly of the World Health Organisation in Geneva (1948), he obtained leaves of absence to conduct national TB surveys for the WHO in Ceylon (1956) and British Somaliland (1957), employing the methodology of the Irish survey. He obtained similar leave to serve as WHO chief of mission in Indonesia (1958–60). He resigned from Irish government service to become chief of senior staff training at WHO headquarters in Geneva (1962–7). After writing the WHO's fourth report on the world health situation (1963–8), he performed short-term WHO consultancies in Syria and the USSR, and served as the WHO's first ombudsman, retiring in 1975. While serving as a locum dispensary doctor in the Fanad peninsula, Co. Donegal (1970–71), he conducted a socio-economic study of the local community, which included analysis of how the community's savings were channelled by the banking system to finance development in urban centres, while the Fanad economy stagnated. His study of the Irish labour force was published as The Irish worker (1971). Appointed special scientific adviser to the Holy See (1971–2), he assisted in the establishment of Cor Unum, a pontifical council that coordinated the work of catholic charities worldwide.

During his years in the Department of Health, Deeny resided at Dunkeld, Portmarnock, Co. Dublin. In 1971 he moved to Rathdowney House, Rosslare, Co. Wexford. He reared cattle in both locations. Deeply involved in the local community in Wexford, he helped found the Tagoat community council, which engaged in housing programmes, care for the elderly, training for the unemployed, and restoration projects. He was named Irish Life Assurance pensioner of the year in 1988. His recreational interests included yachting, genealogy, and collecting oriental ivories. He was awarded an honorary doctorate by QUB (1983), and was active in the Knights of Malta. He wrote an autobiography, To cure and to care (1989); a posthumous selection of his scientific articles, The end of an epidemic (1995), includes a biographical introduction by Ruth Barrington. Deeny married (1934) Gemma Mary McCabe, of Weston, Rathgar Rd, Rathmines, Dublin; they had two sons and two daughters. He died 3 April 1994 at his home.

GRO; T. Corcoran, The Clongowes record (1932); Ruth Barrington, Health, medicine, and politics in Ireland 1900–1970 (1987); James Deeny, To cure and to care: memoirs of a chief medical officer (1989); Joseph Robins, Customs House people (1993); Ir. Times, 4 Apr., 3, 7 May 1994; Independent (London), 20 Apr. 1994; Times, 22 Apr. 1994; Daily Telegraph, 5 May 1994; James Deeny, The end of an epidemic: essays in Irish public health, ed. Tony Farmar (1995); John Horgan, Noel Browne: passionate outsider (2000); Greta Jones, ’Captain of all these men of death’: the history of tuberculosis in nineteenth and twentieth century Ireland (2001); RIA library: members lists and members database

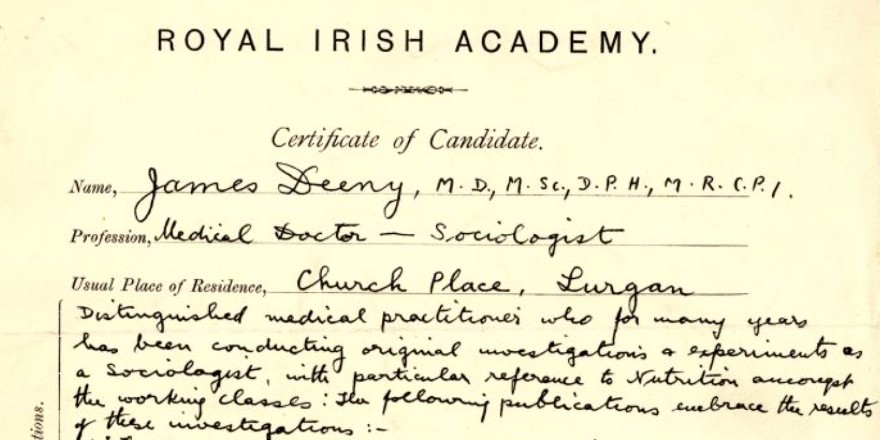

Image: A portion of Deeny's MRIA election certificate, digitised by the RIA Library.