Favourite DIB lives: John Atherton, woeful sinner

03 April 2020Selected by RIA historian Dr John Gibney (Documents on Irish Foreign Policy), John Atherton was an infamous seventeenth-century cleric. Atherton's biography is part of a series of DIB entries selected for your reading pleasure during this challenging time.

Introduction by John Gibney

The circumstances of John Atherton’s demise make him one of the more eye-catching of Anglican bishops. His life and career, as explored here, open an unexpected window into some darker realities of early modern Ireland, as he is revealed as possibly a sexual predator and definitely as a hatchet man for a colonial government. Aidan Clarke’s elegant and occasionally droll entry explores Atherton’s world as much as the man himself, and also showcases one of the great strengths of the DIB: as a repository of excellent and insightful writing, as much as a work of reference.

I came across Atherton when Clarke supervised my doctoral thesis (he first wrote on Atherton in the 1970s, when I was a toddler). I paid my way through much of my studies by working as a tour guide in Dublin, and when I was bringing groups around Christ Church and Fishamble St, for some reason I was always struck that the final end of Atherton's story lay hidden beneath the modern streetscape in that part of the old city.

John Atherton

by Aidan Clarke

Atherton, John (1598–1640), churchman, was born in Somerset, England, son of John Atherton, rector of Bawdrip (nothing is known of his mother), and was educated at Lincoln College, Oxford, where he took his MA degree (1621). Although he showed promise in canon law, his marriage to Joan Leakey, daughter of a Minehead merchant, disqualified him from fellowship and he took up a position as rector of Huish Champflower, Somerset, in 1622. An incestuous affair with his sister-in-law, who bore him a child in 1623, may be said to have set the tone of his life and probably influenced his decision to take up a new career in Ireland.

He was elected to fellowship in TCD in August 1629. The preliminary negotiations appear to have taken it for granted that Atherton would not be affected by the concurrent introduction of a marriage bar in future appointments, but this proved to be mistaken and Atherton did not take up his post. Amends were made when the university incorporated him as an MA in the autumn and secured his appointment to the Christ Church prebend of St John the Evangelist in April 1630. He remained in Dublin, where he quickly caught the attention of Viscount Wentworth, who came to Ireland as lord deputy in August 1633. Rapid promotion followed. In 1634 he was installed as chancellor of the diocese of Killaloe, was appointed rector of Killaban and Ballintubride in Queen's Co., and became chaplain to the lord chancellor. He supported the official policy of replacing the articles of the Church of Ireland in convocation early in 1635, was awarded an honorary doctorate by the university (June), and was installed as chancellor of Christ Church (December). In February 1636 he became a member of the commission for ecclesiastical causes and in May he was consecrated bishop of Waterford and Lismore.

The last stage of this progression had proved problematic. Atherton had neither relinquished his Somerset living, nor applied for licence to hold the two together. Both the lord chancellor and the lord deputy tried to have this omission rectified when it came to their attention, but Archbishop Laud refused permission and Atherton returned to England in 1635 to divest himself of his benefice. Laud suspected that he was arranging to sell his interest, intervened to prevent simony, and was reluctant to put Atherton's name forward for a bishopric when Wentworth proposed him. Wentworth argued for the nomination in terms of his general policy of trying to recover church property from lay intrusion, and insisted on Atherton's particular suitability for this post, which would involve facing down the earl of Cork: if he were appointed, ‘Cork would think the devil is let loose upon him forth of his chain. I will undertake that there is no such terrier in England for the unkennelling of an old fox’ (Wentworth to Laud, 9 March 1636; Sheffield Central Library, Wentworth Woodhouse MSS, vi). Wentworth's assessment was justified in the event, for Atherton quickly forced the earl to an arbitration settlement which raised the income of the combined sees from £50 to £1,000 a year and yielded a capital sum of £500 to build an episcopal palace.

Laud's reservations were bizarrely reinforced when a commission was appointed in January 1637 to inquire into a reported apparition at Minehead. The ghost proved to be that of Atherton's mother-in-law, Susannah Leakey, whose purpose in returning was to require her daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, to go to Ireland to deliver a message to Atherton. Elizabeth refused to disclose the message and the commissioners reported that the apparition was certainly an invention, but professed themselves unable to divine its purpose. Laud was less guarded and suggested to Wentworth that it was ‘some money business’ (The works of William Laud, vii, 327). Wentworth's response was jocular: ‘if money be that they aim at, it must be a strong and crafty devil that gets anything out of the bishop's purse’ (Wentworth to Laud, 10 July 1637; Wentworth Woodhouse MSS, vii). The local tradition, recorded a generation later, was that the message called for Atherton's repentance of an incestuous relationship with his wife's niece and the infanticide to which it had led, but the commissioners' inconclusive report brought the matter to an official end.

In 1638 Wentworth proposed Atherton's transfer to the bishopric of Cork, where he estimated that there was £800 a year to be recovered, but Laud preferred another candidate and Wentworth acquiesced. Atherton took his seat in the parliament which convened in Dublin in March 1640 and which came under the control of a coalition opposition majority after Wentworth left Ireland at the end of the first session. On 17 June 1640, when the commons was considering ecclesiastical grievances, a petition was received from Atherton's proctor, John Child, who claimed to have had homosexual relations with him and accused him of acts of adultery and fornication. On the petition of the commons, Atherton was formally committed to prison, but at once released on bail. When it became clear that he was defiantly intending to join his fellow bishops and the peers in attendance on the lord deputy at service in the cathedral, he was committed to Dublin castle. The collection of evidence was reported to have disclosed innumerable instances of misconduct, and although Atherton strenuously denied the capital charge of sodomy he admitted to ‘some adulteries and fornications’ (PRO, SP, 161/461.32). Rape was included in the charges, but incest, which was freely alleged against him in a discussion of the case in the English house of commons, was not. He was tried in the court of king's bench, found guilty on 27 November of sodomy with Child, and sentenced to execution.

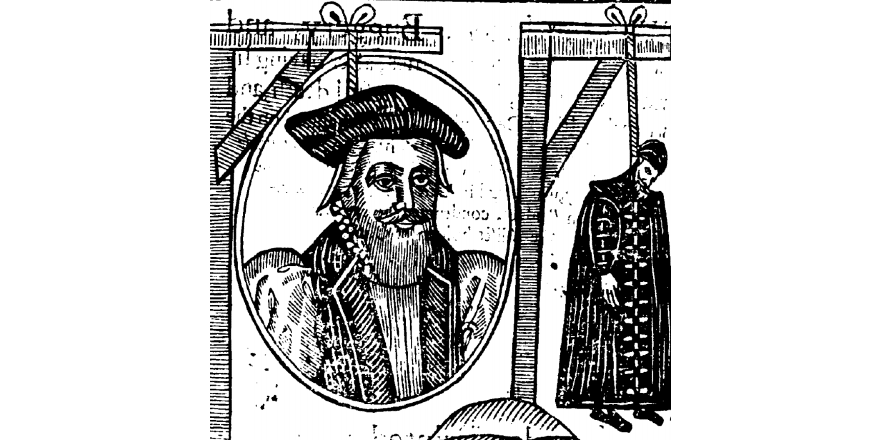

On 5 December 1640 he was hanged on Oxmantown Green and his body interred, at his own request, in a rubbish dump in the corner of the churchyard in Fishamble St. He was survived by his wife and five daughters. The address delivered at his burial service by Nicholas Bernard, dean of Ardagh, who had acted as his spiritual counsellor during his last days, was published in April 1641 under the title The penitent death of a woeful sinner. It had three themes: that Atherton's behaviour discredited himself, not his church; that he was fully repentant and ready for death; and that he had been wrongly convicted of sodomy. Not all of his colleagues agreed with the last point, but posterity has been prone to do so. The presumption has been that, in the words of Thomas Carte, ‘he suffered for a pretended crime’ contrived by one or other of those who had been affected by his rapacious repossession of church property (Life of James, first duke of Ormond (1851), i, 67–8). No evidence of this contrivance has been found: if it were, it would have no bearing on his guilt, since it is no less likely that his accusers exploited his homosexual acts than that they invented them.

Sources: Aidan Clarke, ‘A woeful sinner: John Atherton’, Vincent P. Carey and U. Lotz-Heumann (ed.), Taking sides? Colonial and confessional mentalités in early modern Ireland (2003), 138–49 (full list of sources)

Image: 'The shamefull ende' in The life and death of John Atherton, Lord Bishop of Waterford and Lysmore (1641)