Favourite DIB Lives: Róisín Walsh, Dublin City chief librarian

22 April 2020Selected by Dr Kate O'Malley, managing editor of the DIB, Róisín Walsh (1889–1949) was Dublin's first chief librarian, as well as a feminist and republican. This biography is part of our 'Favourite DIB lives' series selected by staff academics and friends of the RIA.

Introduction by Kate O'Malley

I first encountered Róisín Walsh during research for Documents on Irish Foreign Policy VI. I chanced upon a file in the National Archives of Ireland containing an elegantly crafted and beautifully written account of a library tour of the US. It provided a unique insight into mid-twentieth century America, replete with amusing descriptions of New York cab rides and commentaries on political and social life.

But how did she end up on such a tour in 1939, decades before my own mother would encounter restrictions as a result of the marriage bar?

Crucially, she never married, which allowed her to become not only Dublin City's first chief librarian but one of the world's first female head librarians. Walsh reached the apex of her career a mere eight years after becoming a librarian in 1931. During her term as chief librarian she oversaw a major expansion of Dublin's library service to accommodate the rapidly growing city and suburbs. Under her tenure some of the city’s best-known libraries were expanded or established in Terenure, Marino, Inchicore, Drumcondra, Phibsborough and Ringsend.

A progressive librarian, during her tenure she argued in favour of improving literacy levels and lobbied for further funding for library services nationwide. She was a regular speaker at literary events and conferences, and a frequent voice on Radio Éireann. She held the Dublin City librarian post until her untimely death in 1949. Her impact was enormous – increasing our collective and free access to books and giving us the space and tools to read them. Read her DIB entry, below, which happily, is co-written by two women librarians.

Róisín Walsh

by Evelyn Conway and Deirdre Ellis-King

Walsh (Breathnach), Róisín (1889–1949), librarian and republican, was born on 24 March 1889 into a staunchly nationalist catholic family in the townland of Lisnamaghery, Clogher, Co. Tyone, the eldest of eight children (five sisters and two brothers) of James Walsh (d. 1925), a national school teacher, farmer and native of Co. Monaghan, and his wife Mary (née Shevlin). Raised on the maternal family farm at Clogher, she was named formally Mary Rosalind, otherwise referred to as Mary Rosaleen, but known as Róisín. The family's prime sixteen-acre holding gave them the financial means to ensure that young Róisín, who was a gifted scholar, received the best education then available to females. She commenced her secondary education (c.1901) in the most exclusive convent boarding schools then in place for catholic girls, attending both St Louis Convent, Monaghan town, and Dominican College, Eccles Street, Dublin. A brilliant linguist, she graduated BA (honours) at UCD in Irish, French, German and English in 1911. In that same year she taught English and German at her alma mater, St Louis Convent, and later completed her higher diploma in education from Cambridge University. She taught abroad at Altona High School, Germany (1913–14), leaving because of the outbreak of the first world war.

On her return to Ireland in 1914, she was employed at St Mary's Training College, Belfast (then a primary-school teacher training college for catholic women) as a lecturer in Irish and English. From then until the Easter rising she was closely linked in the nationalist independence movement with Nora Connolly (Nora Connolly O'Brien) and her sister Ina, the Belfast-based daughters of James Connolly. She became a member of the Belfast branch of Cumann na mBan (exceptional in training its members in shooting) from its foundation by Nora Connolly in 1915. Prior to this time she came into contact with Séan Mac Diarmada on his travels throughout Ulster as a Sinn Féin organiser, and helped him with correspondence to the US prior to 1916.

At home in Clogher in Easter week, she received advance knowledge of the rising on Good Friday from IRB activist and Clogher parish priest Fr James O'Daly. Owing to the confusion that followed the countermanding order issued by Eoin MacNeill on Easter Sunday, the northern Volunteers' mobilisation in Tyrone was short-lived and soon dispersed. The Walsh family collectively and in close collaboration with the Connolly sisters, Archie Heron and other IRB activists played a key role in the concerted but blighted attempt to bring about a remobilisation, providing a safe house and carrying dispatches. On Wednesday of Easter week, Róisín Walsh, with her brother Tom and sister Teasie, helped to smuggle ammunition and supplies to the Clogher Company, which had been assembled on Tuesday in the Clogher mountains and at Ballymacan, on the orders of Fr O'Daly. Walsh remained active in the movement in the following years, leaving her teaching post in Belfast by 1919, possibly owing to political harassment, and returning to Clogher.

In mid 1921 she was appointed by Tyrone County Council as their first ever female rate collector, assigned to the rural Clogher district. She was highly regarded as a 'first-rate collector' (Ulster Herald, 18 November 1922), but was reluctantly dismissed by the council in November 1922, after her refusal to sign the declaration of allegiance to the king and the Northern Ireland government. After an RUC raid on her family home in Lisnamaghery in November 1922 discovered allegedly seditious literature, she was forced to flee to avoid arrest and prosecution, moving to Dublin; an exclusion order was put in force against her by the Northern Ireland authorities.

By December 1922 her public library career had commenced (she later obtained her associateship of the Library Association (UK) (ALA) in 1928) when her outstanding credentials secured her the post of assistant librarian in charge of the children's library in Rathmines, which formally opened in May 1923. In the same year, the entire Walsh family relocated south, purchasing Cypress Grove House and farm in Templeogue, Dublin. Walsh's library career subsequently took her to Galway in 1925 as assistant librarian, and in 1926 she was appointed chief librarian in the then largely rural county of Dublin. Her administrative and management skills came into focus in this role, enabling her to pursue new developments to a level whereby she brought the libraries of Co. Dublin to 'the first rank of the county libraries in the Free State' (Ir. Times, 24 July 1931). During this time she became active in the movement towards professionalism in public libraries, being elected to the first executive board of the newly formed Library Association of Ireland in 1928, and chair of the board in 1941.

Walsh's final career move was to Dublin city where she was appointed chief librarian in 1931 in the wake of local government reorganisation which followed the passage that year of the Greater Dublin act. Subsequent boundary changes brought into the city the key libraries of Pembroke and Rathmines, previously operated as independent urban district libraries. The appointment heralded the beginning of Dublin city's modern library service in enabling a coordinated approach to be taken to the combined resource offered by seven major branch libraries. Walsh overcame the management challenges involved and developed plans to meet the library needs of Dublin's growing suburbs, with new buildings erected in Inchicore, Drumcondra, Phibsborough and Ringsend in 1936–7.

Other infrastructural developments followed, but Walsh's vision of the role of chief librarian was rooted in her earlier career in education and allied to her political background. Critically, she believed in 'revolution by education … for there can be no progress until the people have been educated first' (Brooklyn Eagle, 23 November 1934). Armed with a desire to increase access to educational opportunity and building on her interest in Irish literature, she assumed the role of revolutionary educator, using the city library network to broaden access to books in the Irish language and by Irish authors. With the assistance of the Department of External Affairs and the support of Eoin MacNeill, she sought also to spread awareness of the strength and depth of Irish literature and culture among wider audiences in the USA. Equipped with a collection of Irish-interest publications and her considerable oratorical skills, Walsh in 1939 undertook a ground-breaking tour of many American cities where she delivered numerous presentations on topics of Irish interest.

Her knowledge and interests also saw her active on the Dublin cultural, political and social scene where she continued, after 1916, to associate with like-minded republican and left-wing political thinkers. She potentially put her job at risk by allowing her home to be used in 1931 for a meeting at which the left-wing republican party Saor Éire, was launched. She also served on the first editorial board of the literary magazine The Bell (founded 1940) alongside fellow board member Peadar O'Donnell. A committed feminist, Walsh moved in the same circles as Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Mary Hayden and Maud Gonne MacBride, and was a regular guest speaker at the weekly meetings of the Women's Social and Progressive League founded in 1943 by Sheehy-Skeffington.

Walsh drew inspiration from many influences which were sustained by an inter-connecting circle of friends and associates. Key influences included her nationalist family background, which supported her active involvement in revolutionary politics; her university education, uncommon for females of her generation, which exposed her to intellectual rigour; and her travels abroad, which exposed her to different political viewpoints. Her library career allowed her to develop her interests in education and Irish culture and promote them to practical effect. Critically, Walsh took a pragmatic approach to effecting change in the aftermath of rebellion, moving beyond armed revolution and engaging with the needs of Irish people for education, using the tools of knowledge as a first step to real freedom. This culminated in a successful career as Dublin city's first chief librarian. Essentially, she was both a political and a cultural activist who managed to blend potentially conflicting convictions and apply them to the challenge of transforming Irish society. Walsh's actions in the period leading to Irish independence gave her a voice in the making of Irish history. Her career as a librarian who assisted in furthering the education of Irish people, gave her a voice in enabling a better future for everyone.

Róisín Walsh died at her Templeogue home on 25 June 1949, aged just 60 years, and was laid to rest in the family plot at Templeogue cemetery, Dublin; she never married.

Sources: GRO (birth and death certificates); NAI: Census of Ireland, 1901; Nora Connolly, The unbroken tradition (1918); Ulster Herald, 14 May 1921; 28 Oct., 18 Nov. 1922; 10 Mar. 1923; Freeman's Journal, 12 Dec. 1922; 15 Feb. 1923; File relating to the prosecution of James Walsh 1922–3 (PRONI, HA/5/283); Ir. Times, 24 July 1931; 'Memorandum on Irish cultural interests in the United States… ' (copy), 13 Oct. 1938 (DIEF Documents on Irish Foreign Policy, no. 234 (NAI DT S9215)); Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 23 Nov. 1934; Library Association of Ireland, 'Minutes of the executive board, 1928–41'; Róisín Walsh. 'Statement regarding Ina Connolly's (Mrs A. Heron) part in the 1916 rising in Co. Tyrone' (1938) (Military Archives (Ireland), IE/MA/MSPC/MSP34REF21565, www.militaryarchives.ie); Ir. Press, 25 June 1949; Connacht Tribune, 2 July 1949; BMH, witness statements, www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie: James O'Daly (WS 235), Nora Connolly O'Brien (WS 286), Archie Heron (WS 577), Ina Heron (WS 919); Róisín Walsh: will and associated papers, 1950 (NAI, CS/HC/PO/4/103/11297; Peadar O'Donnell, There will be another day (1963); Rosemary Cullen Owens, Smashing times: a history of the Irish women's suffrage movement, 1889–1922(1984); Deirdre Ellis-King, 'Dublin public libraries: an overview' in Library Association of Ireland, Libraries of Dublin: proceedings of a conference held on 14th–16th October 1988 (1989), 24–33; Margaret Ward,Unmanageable revolutionaries: women and Irish nationalism (1995); Gerard MacAtasney, Seán MacDiarmada: the mind of the revolution (2004); Margaret Ward, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington: a life (1997); Eamon Phoenix, 'Nationalism in Tyrone, 1880–1972' in Charles Dillon and Henry A. Jeffries (ed.), Tyrone: history and society (2000), 765–808; 'Manifesto of IWSPL' (1943) in Angela Bourke at al (ed.), Field Day anthology of Irish writing, v (2002), 166–7; Deirdre Ellis-King and Evelyn Conway, Róisín Walsh (1889–1949): Dublin city's first chief librarian: a brief biographical account with a bibliography of key writings by and about her (2010); Kate O'Malley, 'Róisín Walsh's report of a visit to American libraries, universities and other institutions, 1939' in Analecta Hibernica, xliv (2013), 121–243; Cumann na mBan mural wall, www.ul.ie/wic/content/cumann-na-mban-mural-wall (accessed Sept. 2015)

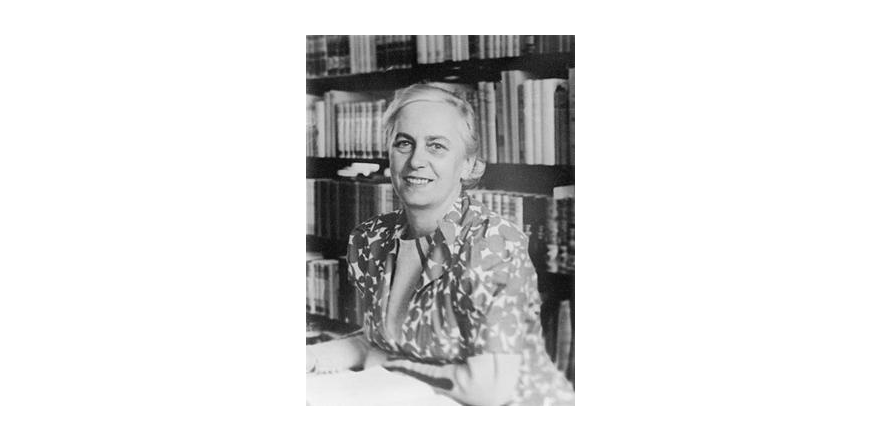

Image: Róisín Walsh, courtesy of Dublin City Public Library and Archives.