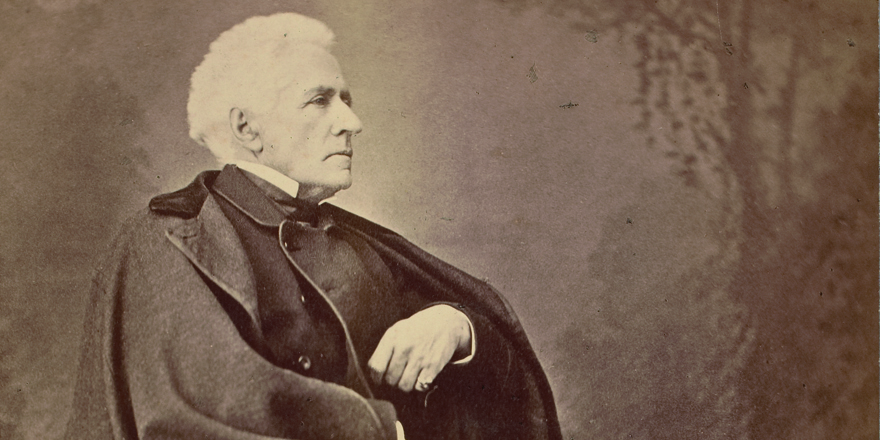

Forgotten Polish Hero of the Great Irish Famine: Paul Strzelecki

10 June 2019Read the DIB entry for Paul Strzelecki, the Polish humanitarian whose efforts saved up to 200,000 children during the Great Irish Famine.

by Desmond McCabe

Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki (1797–1873), explorer and humanitarian, was born 20 July 1797 into the Polish aristocracy in Prussian-occupied Poland, the son of Francis Strzelecki and his wife Anna (née Raczynski). The family went into exile in the UK in the early 1800s. Strzelecki was educated at the High School, Edinburgh, matriculated (1815) at Oxford, and graduated BA (1820). He lived the life of a gentleman of independent means in England until 1834, when he set out on a privately funded expedition of inquiry to China and the Far East. On his passage home (1839) he visited Sydney, where he met Sir George Gipps, governor of New South Wales, who urged him to investigate as yet unknown tracts of the Great Dividing Range to the south of the state. Assembling a team of scientists at his own expense, he spent close to a year in the mountains and outback, soon discovering a rich seam of gold ore in the quartz bedrock on the plains of Wellington – the first such find on the continent. He finally decided to complete the venture with an attempt on a difficult route south to Melbourne. Having run out of supplies, the team was fortunate to reach settled territory after nearly a month of starved, tortuous progress through dense scrub. He was persuaded by Gipps (who feared an outbreak of social disorder) not to mention the find of gold in the official report of the expedition. His personal account of the scientific results of the expedition, published (London, 1845) two years after he returned to England, maintained this reserve.

On 1 January 1847 he was appointed Irish agent to the British Relief Association (BRA), responsible for the distribution of food and clothing in the impoverished districts of Mayo, Sligo and Donegal. It was said that the BRA felt that he would be more acceptable in this role than an English bureaucrat, and certainly, from the outset, he showed no inclination to allow establishment thinking to shape his judgements. This was all the more remarkable as the BRA chose to channel its relief through state organisations, subject to the full supervision and control of the treasury department. Strzelecki was obliged therefore to act as a kind of supernumerary civil servant. During January 1847 he assured the businessmen on the BRA committee that conditions around Westport exceeded in horror anything he had seen before. Most of the initial relief capital was expended, nevertheless, in loans (rather than grants) to distressed unions between January and April 1847, strictly according to treasury guidelines. In late May 1847 Strzelecki was given charge of the distribution of a parliamentary subscription for Irish distress, in the amount of £10,000. In August he strongly argued that a balance of £200,000 in BRA funds should be spent feeding children attending school in those twenty-two poor law unions designated as ‘distressed’. In the teeth of protests by Charles Trevelyan, secretary of the treasury, Strzelecki prevailed on the conservative BRA committee to launch the scheme with a small proportion of the funds (£12,000 initially). He worked tirelessly to have this fund increased in order to prolong the relief of children, with rations of rye bread and broth, month by month into the official aftermath of the crisis, estimating in correspondence that a mere third of a penny daily ensured the subsistence of each child. Between October 1847 and July 1848 the BRA submitted some £92,968 to the treasury for dispersal to national schools inspectors and teachers for attending children. In March 1848 c.200,000 children were supported by the fund.

At this period Strzelecki was also advising that destitution was as great a danger as lack of food to the health of the western population and was attempting to funnel capital into temporary poor law accommodation. Between January 1847 and August 1848, when funds dwindled, the BRA expended about £250,000 in relief to pauperised adults and children. This comprised the greater part of the total sum spent in relief under the control of the treasury in the period. Though Strzelecki was formally chief administrator of the Irish BRA fund, in practice (with the exception of the schoolchildren scheme) he was usually confined by the BRA committee to the service of treasury instructions. Leaving Ireland on 12 September 1848, when the organisation was closed, he declined to accept payment for his relief work, explaining: ‘I never could justify myself to my inner tribunal if I were to take money for what I have gone through’ (quoted in Woodham-Smith, 365). Coming back to Ireland in June 1849 to distribute a small parliamentary fund raised that month, he remained acutely aware of the depth of crisis despite official optimism, declaring to a commons committee of inquiry later that year that smallholders were ‘skinned to the bone’ (ibid., 375) by successive years of famine.

Strzelecki's close contact with the starving and his chivalrous personality made him one of the most responsive agents of relief during the famine. His sympathetic and respectful portrayal, in committee, of the Irish catholic clergy served as a corrective to wilder anti-papist elements in British politics at the time. During the early 1850s he was naturalised as a British subject and acted as government adviser on Australian affairs. In 1855 he took part in the Crimean army fund committee. He died 6 October 1873 at his residence in Savile Row, London. There is a considerable holding of his official correspondence in the Irish famine papers in the National Archives (Kew).

On Wednesday 12 June, the Royal Irish Academy is hosting a lunchtime lecture starting at 1pm on Strzelecki's fascinating life and achievements, the event is free and open to all. The Academy is also currently hosting a free exhibition on Strzelecki in conjunction with the Polish Embassy which runs until 30 August 2019.

Sources: Cecil Woodham-Smith, The great hunger: Ireland 1845–9 (1962); Donal Kerr, ‘A nation of beggars’: priests, people and politics, 1846–1852 (1994); Christine Kinealy, This great calamity: the Irish famine, 1845–52 (1994); Peter Gray, Famine, land and politics: British government and Irish society, 1843–1850 (1999); ODNB

© 2019 Cambridge University Press and Royal Irish Academy. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Learn more about DIB copyright and permissions.