Lynn and Dunlevy: leading the fight against TB

23 November 2020In the final article of our three-part series on public health and infectious disease, we look at the development of ‘public health’ in Ireland, considering key figures in the area of tuberculosis eradication: Kathleen Lynn (1874–1955) and Pearl Dunlevy (1909–2002).

Biographies introduced by Turlough O'Riordan, DIB

The prevalence of preventable disease, and the devastating level of infant mortality, in early twentieth-century Dublin induced a range of public health responses. The establishment of St Ultan’s Hospital in Dublin, in the aftermath of the 1919 influenza epidemic, became the bedrock for infant and maternal public health provision in Dublin. Two DIB lives demonstrate important new perspectives in medicine and public health introduced by innovative women doctors in twentieth century Ireland.

Founded by Kathleen Lynn (1874–1955), with Madeleine ffrench-Mullen, St Ultan’s Hospital was central to the training and recruitment of women doctors who were elsewhere excluded from medical training and practice. The focal point for the introduction of the BCG tuberculosis vaccine into Ireland, St Ultan’s fostered pioneering public health initiatives to combat the pernicious effects of social deprivation and urban poverty.

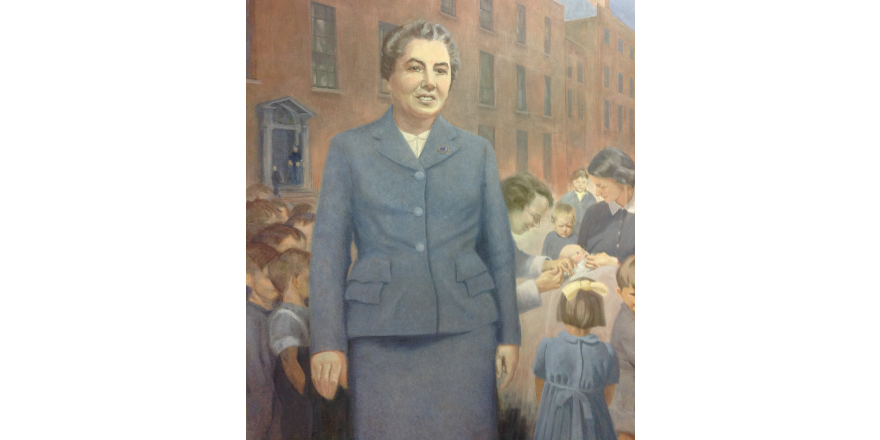

The slums of post-war Dublin were wrought with endemic poverty and human suffering. Crowded housing, widespread malnutrition, poor sanitation and limited medical provision remained a considerable blight on the urban poor, especially children. Pearl Dunlevy (1909–2002) – one of the leading medical students of her generation, though unable to attain training positions in Irish hospitals – brought international best-practice, rigorous data collection and analysis, as well as her own personal tenacity, to bear on childhood TB in Dublin.

Kathleen Lynn (1874–1955)

by Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh

Lynn, Kathleen (1874–1955), medical practitioner and political activist, was born 28 January 1874 in Mullafarry, near Cong, Co. Mayo, second oldest of three daughters and one son of Robert Lynn, Church of Ireland clergyman, and Catherine Lynn (née Wynne) of Drumcliffe, Co. Sligo. Despite aristocratic relations and a comfortable upbringing, her professional career was primarily concerned with the less well-off. Lynn's Mayo childhood, where poverty coincided with land agitation, may have motivated her to seek political and pragmatic solutions to socio-economic deprivation. After education in Manchester and Düsseldorf, she attended Alexandra College, Dublin. She graduated from Cecilia Street (the Catholic University medical school) in 1899, and, after postgraduate work in the United States, became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1909. She was refused a position in the Adelaide Hospital because of her gender, and eventually joined the staff of Sir Patrick Dun's Hospital. Valuable experience was also gained at the Rotunda Lying-In Hospital. From 1910 to 1916 she was a clinical assistant in the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital, the first female resident doctor at the hospital, but was not allowed to return after the 1916 rising. Her private practice, at 9 Belgrave Road, Rathmines, was her home between 1903 and 1955.

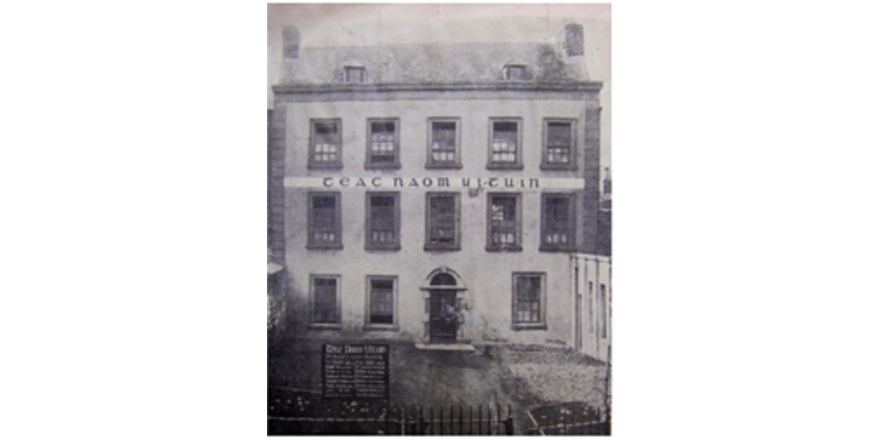

An active suffragist and an enthusiastic nationalist, Lynn was greatly influenced by labour activists Helena Molony, Constance Markievicz and James Connolly. Her work in the soup kitchens brought her into close contact with impoverished families in Dublin during the 1913 lock-out of workers. She joined the Irish Citizen Army and taught first-aid to Cumann na mBan. As chief medical officer of the ICA during the 1916 rising, she tended to the wounded from her post at City Hall, and her car was used for the transportation of arms and for Markievicz to sleep in. Imprisoned in Kilmainham, with her close friends Helena Molony and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen, she complained bitterly about the cramped prison conditions. A committed socialist, she was an honorary vice-president of the Irish Women Workers' Union in 1917 and denounced the poor working conditions of many women workers. She was vice-president of the Sinn Féin executive in 1917, and her home was a meeting point for fellow Sinn Féin women, notably for meetings of Cumann na dTeachtaire (the league of women delegates). On the run between May and October 1918, she was sent to Arbour Hill detention barracks when arrested. The authorities agreed to release her, on the intervention of the lord mayor of Dublin, Laurence O'Neill, as her professional services were essential during the 1918–19 influenza epidemic. Despite her high political profile, Lynn is remembered, primarily, for her work in St Ultan's Hospital (pictured below) for Infants on Charlemont St., which she established in 1919 with her confidante, Madeleine ffrench-Mullen. Its philosophy was to provide much-needed facilities, both medical and educational, for impoverished infants and their mothers.

Though she was active in south Tipperary during the war of independence, Lynn's national prominence faded after the heady 1913–23 period. In 1923 she was elected to Dáil Éireann as Sinn Féin candidate for Dublin county on the anti-treaty side, but did not take her seat. She failed to retain her seat in the June 1927 election but was an active member of Rathmines urban district council between 1920 and 1930. She commented regularly on public-health matters such as housing and disease prevention. As council member of the Irish White Cross she endeavoured to help republicans and was very critical of the newly formed Irish Free State's attitude to anti-treatyites. At St Ultan's, Lynn fostered international research on tuberculosis eradication. In 1937, through the efforts of her colleague Dorothy Stopford-Price, the hospital introduced BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin) inoculation, which prevented TB. She also encouraged links with US and continental medical practitioners. Ffrench-Mullen and Lynn visited the United States in 1925 to raise funds for St Ultan's and visit paediatric institutions. Lynn's interest in child-centred education was furthered in 1934 when Dr Maria Montessori visited St Ultan's.

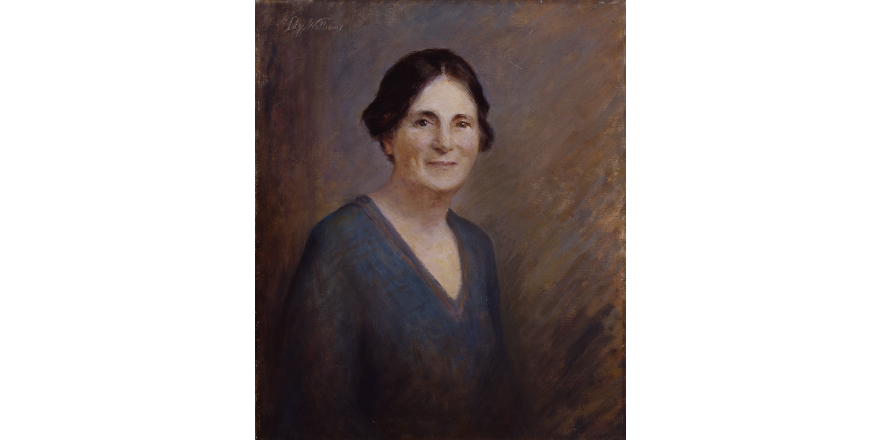

Throughout her life Lynn preached the virtues of cleanliness and fresh air. She was involved with An Óige (a youth organisation) and gave them her cottage in Glenmalure, Co. Wicklow (which she had previously lent to Dorothy Macardle for the writing of The Irish republic). Lynn's friend, the architect Michael Scott, designed a balcony outside her bedroom, where she slept for most of the year. A devout member of the Church of Ireland, she worshipped regularly at Holy Trinity church, Rathmines, but often criticised the Christian churches for losing sight of Christ's original teaching. After World War II, she was vice-chairman of the Save the German Children Society. She died on 14 September 1955 at St Mary's Nursing Home in Dublin and was given a full military funeral. Remembered primarily for her socio-political activism, she was part of a generation of women who were politicised in the 1910s and who devoted their later careers to maternal feminism. A portrait by Lily Williams is in the Royal College of Physicians, Ireland.

Revised: November 2013

Margaret ('Pearl') Dunlevy (1909–2002)

by Turlough O'Riordan

Dunlevy, Margaret ('Pearl') (1909–2002), physician and epidemiologist, was born Bridget Margaret Mary Dunlevy on 13 August 1909 at Mountcharles, Co. Donegal, the fifth of six children (four boys and two girls) of George Dunlevy, shopkeeper and merchant, and Maggie Dunlevy (née Doherty).

After attending the Loreto Convent, St Stephen's Green, Dublin, and St Louis Convent, Carrickmacross, Co. Monaghan, Dunlevy commenced medical studies at the RCSI. Taught by Sir Thomas Myles, she graduated (1932) first in her final medicine and surgery exams (L and LM, RCSI and RCPI). She then served as house surgeon at the Eye Hospital, Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1932–3), house physician and surgeon at Nuneaton General Hospital (1933), resident surgical officer at Birmingham Children's Hospital (1933–4), medical officer at Sydenham Children's Hospital, London (1934), and house surgeon at Standon Hall Orthopaedic Hospital, Staffordshire (1934–5). On graduating first place in the UCD diploma in public health (1936), she was appointed temporary assistant county medical officer of health in Donegal (1936), then assistant medical officer of health in Dublin (1938), resident at Crooksling tuberculosis sanatorium, Co. Dublin. Developing considerable expertise in the treatment and control of childhood TB cases, Dunlevy, with three medical colleagues from Dublin Corporation's TB service, undertook a six week tour (June–July 1947) of Norway, Denmark (especially the Central Tuberculosis Clinic in Copenhagen) and Sweden to assess the deployment of the BCG vaccine in the region, where childhood TB was rare.

By this time Dunlevy had already established (1945) Dublin Corporation's primary TB clinic at the Carnegie Trust Child Welfare Centre in Lord Edward Street. Isolating children from the dangers of infection when attending the waiting rooms of adult TB dispensaries, the clinic aimed to identify and immediately treat children with TB, successfully minimising their admission to sanatoria (the 150 beds in Dublin were subject to endemic waiting lists). Appointed a Dublin Corporation TB officer (1947), Dunlevy managed a mass x-ray (radiography) programme and commenced tuberculin testing to assess TB infection rates and the likely loci of transmission, aiding identification of the source of infection (usually familial, and linked to crowded housing conditions). She was appointed assistant medical officer for Dublin city (1948), later lamenting that throughout the 1950s medical staff were paid less for tuberculin testing of patients than veterinarians were for the testing of cattle (Dunlevy, IMT, 18 June 1982).

To harness her reputation for organisational and clinical rigour, Dunlevy was handpicked to spearhead a childhood BCG vaccination scheme in Dublin. Her clinical and diagnostic experience (alongside her high regard for the instructive bureaucratic, statistical and medical rigour she had observed in Denmark's public health system) formed the basis of her epidemiological studies, which greatly improved the scheme's effectiveness. Pulmonary TB was then widespread among expectant mothers; the incidence of TB in the city, rising during the wartime emergency, peaked in 1947. Children under five years of age experienced the highest mortality; of the 138 childhood TB deaths in the city in 1947 (81 of which were due to tuberculosis meningitis), 101 were aged five years or less (Dunlevy, IMT, 29 September 1979). Emanating from a Medical Research Council of Ireland committee tasked (1946) with assessing TB treatments and the utility of vaccination (BCG vaccination was first undertaken in Ireland by Dorothy Price at St 's Hospital for Infants from 1937, ceasing at the onset of the emergency in 1939), the Dublin Corporation BCG vaccination scheme commenced in October 1948. Initially focusing on newborn children of TB-infected parents, the scheme gradually expanded to include all newborn children, student nurses and medical students, and later the staff and students of residential schools. By 1949, with radiological screening rapidly identifying those in need of treatment at St Ultan's, childhood TB deaths decreased to 46 (one-third of their 1947 total.)

Concentrating on children who came into close contact with TB sufferers in the home and family, the locations of TB deaths were reported in weekly returns from the general registrar, generating insightful geographical data on the location and spread of infection, facilitating the accurate targeting of specific households, schools and institutions for TB treatment and BCG vaccination. Drawing on a newly cooperative relationship between the Dublin voluntary hospitals and Dublin Corporation, rigorous record-keeping allowed accurate delineation of those receiving the vaccine, valuable when conducting post-mortem investigations into suspected TB deaths in the city. James Deeny later recalled that 'Dunlevy built up from nothing the highly efficient, beautifully organised Dublin scheme, which ran like clockwork, was availed of widely, produced no unfavourable incidents, reduced childhood tuberculosis to vanishing point, and lowered dramatically the awful incidence of tuberculosis meningitis in babies in Dublin. All this was carried out during the very difficult post-war conditions in the city' (Deeny, IMT, 26 February 1982).

Dunlevy was a member of the committee (1948) and of the ensuing government-established limited company (Hospital's Associated Ltd (1949)) that designed and built a TB sanatorium at Ballyowen, Lucan, Co. Dublin, for childhood TB treatment. The success of the Dublin BCG scheme necessitated the late alteration of the plans and function of what became St Loman's Hospital to serve adult TB patients instead. The scheme was extended to those newborns exposed to TB at the Rotunda (September 1950) and the Coombe (1951) maternity hospitals, and then to all newborns (from 1954). The first such local authority scheme in Ireland or Britain, the Dublin Corporation BCG scheme by 1953 had reduced childhood TB deaths by 82 per cent (Deeny, Tuberculosis in Ireland, 235). With parental consent always being sought, over 85,000 children were vaccinated between October 1948 and October 1958, without a single death from TB amongst the group (Dunlevy, BMJ, 27 December 1958). Any childhood deaths from TB in the city, ranging from one to three annually, were among the unvaccinated.

Dunlevy idolised Price, both of whom looked to Scandinavia (Denmark and Sweden respectively) as they wrestled with appalling TB death rates (remaining almost static from 1920 to 1945) for infants aged up to one year. By contrast, conservative (and male) Irish medics took their lead professionally and medically from Britain, which was less exercised by TB and the utility of the BCG vaccine. The support of Deeny, the state's chief medical officer (1944–50), and of Noel Browne, minister for health (1948–51), alongside the impact of the newly established (1947) Department of Health, contributed to the success of the Dublin BCG scheme. Furthermore, the deployment of emergent combinations of antibiotics, the impact of mass diagnostic radiography/x-ray programmes, and the notable increase of sanatoria beds through the 1950s all contributed to a wider decline in TB infection. Appointed (1949) by Browne to the national BCG committee, which under John Cowell gradually expanded BCG vaccinations nationwide concurrently with the separate Dublin scheme, Dunlevy outlived many of her early collaborators to attend the last meeting of the committee in December 1978.

She served effectively as senior assistant chief medical officer in the Dublin Health Authority (1960), which unified all health and public assistance services for Dublin city and county in charge of immunisation services across the city (1960–71). As TB, diphtheria and other infectious diseases gradually receded, from 1965 Dunlevy oversaw a polio vaccination programme in Dublin. She also addressed the epidemiology of rubella (German measles), leading from 1971 a Dublin rubella vaccination scheme for girls aged 12 to 14. Continuing to work closely with the Dublin maternity hospitals, at the end of 1972 she introduced a rubella screening program for those in early pregnancy.

Observing elevated numbers of minor adverse reactions among vaccinated children which were discouraging their mothers from bringing them for subsequent necessary booster injections, Dunlevy was involved with a subsequent 1973 trial led by virus experts Patrick Meenan and Irene Hillary. A combined diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine developed by the Wellcome Laboratories was tested in this regard on fifty-three children housed across five Dublin residential institutions, against a control group of sixty-five children living at home, given a variant vaccine. No significant difference was observed between the two groups and the trial remained unpublished. It has been the subject of repeated controversy regarding both the lack of consent (not then statutorily required) recorded for the institutional participants, and concerns about the safety and impact of certain batches of vaccines used (Irish Independent, 26 June 2001; Commission to inquire into child abuse (December 2003)).

Garnering an international reputation, Dunlevy attended conferences in the UK and Europe presenting on her work. She published in the prestigious French journal Revue de la tuberculose (1951) and undertook further postgraduate training in Paris (1954). Focusing on childhood epidemiology, vaccination and public health, her many papers appeared in the British Medical Journal, the Journal of the Medical Association of Éire, the Irish Journal of Medical Science, and the Journal of the Irish Medical Association. She served as deputy chief medical officer in the Eastern Health Board from 1971 until her retirement in September 1976. Having contributed 'Medical families in medieval Ireland' to What's past is prologue: a retrospect of Irish medicine (1952; ed. William Doolin and Oliver Fitzgerald), into retirement Dunlevy wrote a regular column for the Irish Medical Times, demonstrating her expansive knowledge of the history of medicine in Ireland from ancient times. Highlighting the distinct needs of those with physical and mental impairments, and other vulnerable citizens, Dunlevy viewed with growing concern the decline in parents availing of childhood immunisation schemes for their children, as the pernicious diseases they helped eradicate receded from public and official view.

Elected the first woman president (1951–2) of the Biological Society of the RCSI, she discussed 'The prevention of tuberculosis' in her inaugural address. A long-time examiner for the RCSI's diploma in child health, president of the Irish Society for Medical Officers of Health, and a committee member of the 'women's federation' of the Irish Medical Association, she was a member (1978) and fellow (1980) of the RCPI, as well as a member of the faculty of community medicine of the RCPI, and a fellow of the RAMI.

Having been nursed by her long-time companion Kathleen Hughes, Margaret Dunlevy died 3 June 2002 in Dublin, and was buried in Shanganagh cemetery. Her elder sister Annie ('Nan') Josephine Dunlevy (1903–88), born in Co. Donegal, graduated from the RCSI in 1931; two of their brothers also became doctors. Annie Dunlevy practised as a psychiatrist in Donegal and Dublin, lectured in anatomy at the RCSI, and lived for many years at various Dublin addresses with her sister.

Entry added to the DIB online in December 2015

Sources for Dunlevy

GRO (birth cert.); Pearl Dunlevy papers, RCSI archives; Dorothy Price papers, MSS Dept., TCD Library; Donegal News, 21 May 1932; Ir. Times, 23 June 1936; 25 June 1998; 4, 15 June 2002; Ir. Press, 22 July 1947; Ir. Independent, 15 Jan. 1949; 26 June 2001; M. Dunlevy, 'Lowered tuberculosis death rates in Dublin children', Journal of the Medical Association of Éire (Apr. 1949); ead., 'Infant BCG vaccination', British Medical Journal (13 Mar. 1954); James Deeny, Tuberculosis in Ireland: report of the national tuberculosis survey (1950–52) ([1954]), 233–5; M. Dunlevy, 'Tuberculosis meningitis after BCG', British Medical Journal (27 Dec. 1958); ead., 'Vagaries of BCG-induced tuberculin allergy', Postgrad Medical Journal, xl, no. 81 (1964); ead., 'Striking success of Dublin vaccination programmes', Irish Medical Times, 14 Dec. 1973; Irish medical and hospital directory (1976), 140; Irish Medical Times, 29 Sept. 1979; 26 Feb., 18 June 1982; Alan Browne (ed.), Masters, midwives and ladies-in-waiting: the Rotunda hospital 1745–1995 (1995); Commission to inquire into child abuse: third interim report (Dec. 2003)

Sources for Lynn

Evening Mail, 10 June 1916, 31 Oct 1918; Royal College of Physicians, Ireland, Kathleen Lynn diaries and St Ultan's papers; Christian Brothers archive, Dublin, Br Allen papers; minute book of Cumann na dTeachtaire, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington collection, NLI, MS 21194 (47); Kathleen Murphy, obituary, Journal of the Irish Medical Association, xxxvii (1955), 321; Hazel Smyth, ‘Kathleen Lynn M.D., F.R.C.S.I. (1874–1955)’, Dublin Hist. Rec., xxx, no. 2 (Mar. 1977), 51–7; Lyons, Brief lives, 159–60; Margaret Mac Curtain, ‘Women, the vote and revolution’, Margaret Mac Curtain and Donncha Ó Corráin (ed.), Women in Irish society: the historical dimension (1978), 46–57; Pearl Dunlevy, ‘Patriot doctor – Kathleen Lynn F.R.C.S.I.’, Irish Medical Times, 4 Dec. 1981; Gearóid Crookes, Dublin's Eye and Ear: the making of a monument (1993); W. W. [Canon William Wynne], ‘Kathleen Lynn’, Ir. Times, 9 Apr. 1994; Margaret Ward, ‘The League of Women Delegates and Sinn Féin 1917’, History Ireland, iv, no. 3 (autumn 1996), 37–41; Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh, Dr Kathleen Lynn and maternal medicine (2000); ead., ‘St. Ultan's, a women's hospital for infants’; History Ireland, xiii, no. 4 (July / August 2005), 36–9; ead., Kathleen Lynn, Irishwoman, patriot, doctor (2006)

Images:

'Mycobacterium tuberculosis Bacteria, the Cause of TB' by NIAID licensed under CC BY 2.0

Kathleen Lynn, courtesty of Royal College of Physicians under license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

St Ultan's Hospital, taken from The administrative papers of Saint Ultan’s Hospital, Dublin, 1919–1984. Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (2017)

'Margaret 'Pearl' Dunlevy' by Benita Stoney, courtesy of Royal College of Surgeons Ireland