Ireland leaves the Commonwealth, 1949

18 April 2019In April 1949 Ireland became a republic and left the Commonwealth. What did the Commonwealth think about it?

In January 1949 John Dulanty, Ireland's High Commissioner in London (the senior Irish diplomatic representative), wrote to Frederick Boland, Secretary of what was the Department of External Affairs, to report that Pakistan was unhappy at the prospect of Irish nationals being treated as 'non-foreign'. The letter in question, reproduced above, forms part of the voluminous papers of Frank Aiken, held in UCD, and stands at the intersection of two different eras. The Liverpool-born Dulanty had had a long and varied career (even serving as an election agent for Winston Churchill in 1908), while Boland's own distinguished career would see him touted as a prospective Secretary General of the United Nations in the 1960s.

But the letter alludes to something else; it reflects Pakistan’s concerns that Irish citizens might retain Commonwealth privileges despite having left the organisation.

In April 1949 Ireland became a republic under the stewardship of the Fine Gael Taoiseach John A. Costello. This is a relatively well-known event in Irish history. What is less well known however, is the quiet but profound impact this had upon the British Empire. The aftermath of the Second World War was a critical period in the Empire's history, as decolonisation took hold and mass emigration from the colonies to Britain began; the challenges faced by the Windrush Generation, after all, lie behind the concerns raised in Dulanty's letter above, which touches upon a much bigger story that is worth exploring. When Ireland became a republic, it left the Commonwealth. What did the Commonwealth think about it?

To understand the ramifications of Ireland's final departure from the British Empire one has to glance back to the arrangements that kept independent Ireland in the Empire in the first place. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 created the Irish Free State, a Dominion with a constitutional status modelled on that of Canada. Continued allegiance to the crown ultimately split the independence movement and led to the Irish Civil War, but there were numerous attempts at compromise between the pro- and anti-treaty sides prior to this. Prominent among these was the proposal put forth by Éamon de Valera in the midst of the original Dáil debates on the Treaty: the co-called 'Document No. 2', which proposed a form of 'external association' between the Irish republic demanded by the anti-Treaty faction and the British Empire. The subtleties of this were lost on virtually everyone at the time and it was withdrawn amidst much rancour, to be occasionally disinterred by de Valera's political opponents as embarrassing proof of the insincerity of his professed republicanism.

But after the Second World War this footnote in Irish history - or more properly, its lineal descendent - was revisited by British officials who realised it might offer a solution to a pressing set of imperial problems.

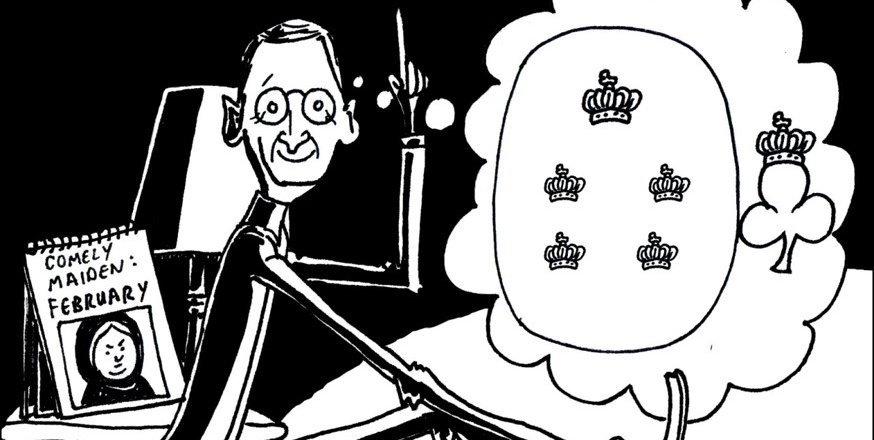

In 1965 de Valera told the historian Nicholas Mansergh that the idea of external association came to him while sitting at the end of his bed tying his bootlaces: ‘he conceived of it first in mathematical terms with a large circle, including five small circles (Britain and the four Dominions) with another small circle outside touching the large circle representing Ireland.’

The idea of full freedom for the so-called ‘white dominions’ of the Empire was barely discussed in London in 1921. This would change with the groundbreaking Imperial Conferences of the 1920s that resulted in the Balfour Declaration and the Statute of Westminster, in which members of the pro-Treaty Cumann na nGaedheal government of W.T. Cosgrave played a significant role.

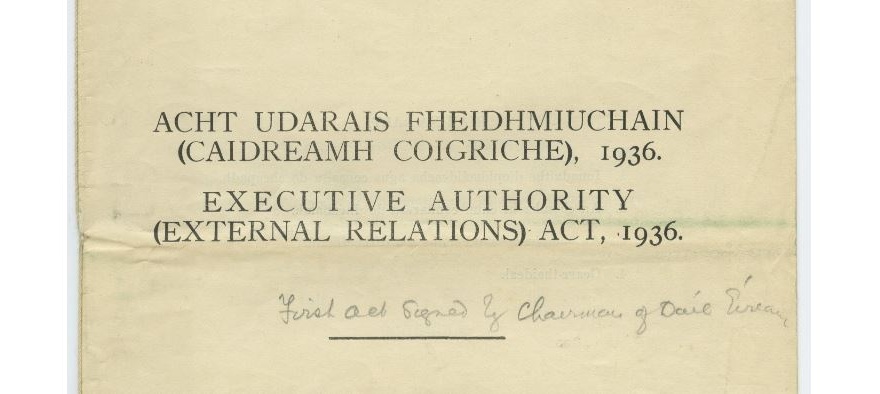

De Valera succeeded Cosgrave in 1932, and the core foreign policy of his Fianna Fáil government was aimed at overturning the 1921 Treaty. The critical milestone here was the passing of the External Relations (Executive Authority) Act of 1936, a constitutional brainchild of de Valera's that retained an external link with the Empire after previous legislation had stripped the role of the crown out of the Free State's internal affairs; essentially, a reboot of Document No. 2. Unlike his predecessors, de Valera was uninterested in exploring the limits of Ireland's status as a Dominion; instead, he ignored it. But crucially, he was unwilling to break away from the Commonwealth: the credentials of Irish diplomats were still authorised by the King, and Ireland remained an associate member of the Commonwealth. These provided continued, albeit tenuous, links to the Empire (ostensibly as a route to allow ultimate Irish unity).

The cover of the External Relations (Executive Authority) Act of 1936 (UCDA P150/2345/3).

The British government’s reaction to this was relatively composed. The Irish government proceeded on the assumption that Ireland was an entirely sovereign independent country that was merely associatedwith the Commonwealth. The British government assumed that, despite their distaste for de Valeras's 1937 constitution, nothing had essentially changed. Crucially, neither insisted on its own interpretation. This remained the status quo until 1948.

After the Second World War Britain began to consider the potential value of repurposing the Empire into a ‘Commonwealth of free nations’, in part to attempt to keep newly independent colonies aligned with the west in the burgeoning Cold War, but also to manage what was increasingly seen as the inevitable dissolution of the Empire in its existing form. Could the Commonwealth evolve into an organisation where independence within a wider framework could be facilitated? The formula that de Valera had devised a quarter of a century earlier took on a new prominence; here was a mechanism that just might offer the best of both worlds, and British officials began to actively recommend the External Relations Act, and the concepts it encapsulated, as a possible model for countries such as India that were moving towards independence.

In Ireland however, the debate was very different. The lack of clarity about its relationship with the Commonwealth and ergo, Ireland’s status as a republic, became a target for de Valera’s opponents. If Ireland was a republic since the passing of the 1937 constitution (dubbed a ‘dictionary republic’, after de Valera had cited several in the Dáil in July 1945 by way of explaining the situation), this was not at that time compatible with Commonwealth membership. And, if a republic, why was the External Relations Act needed at all? John A. Costello had long been a critic of the act and decided to clarify matters by stating at a press conference while on a state visit to Canada in September 1948 that its repeal, when it happened, would mean Ireland had left the Commonwealth. The location for this announcement was incongruous, but that this statement came from a Fine Gael Taoiseach, whose party was considered pro-Commonwealth, made it even stranger.

The uncertainty this prompted was evident. Some senior Irish diplomats were quite uneasy with the prospect. In late 1948 John Dulanty was having what he described as ‘fugitive conversations’ with Commonwealth Prime Ministers attending a conference in London. He was left in no doubt that other Commonwealth countries viewed Costello's move as a mistake. India's Jawaharlal Nehru told him as early as October that ‘it would be prudent on their part to retain some thread, however thin, with the British Commonwealth.’ The Canadian High Commissioner in London, Norman Robertson, didn’t mince his words to Dulanty: ‘It would have been a better plan… to let the Act fall into desuetude. Other statutes had died out that way. No speeches having been made about them, their fading out of the sphere of practical affairs had passed without comment.’

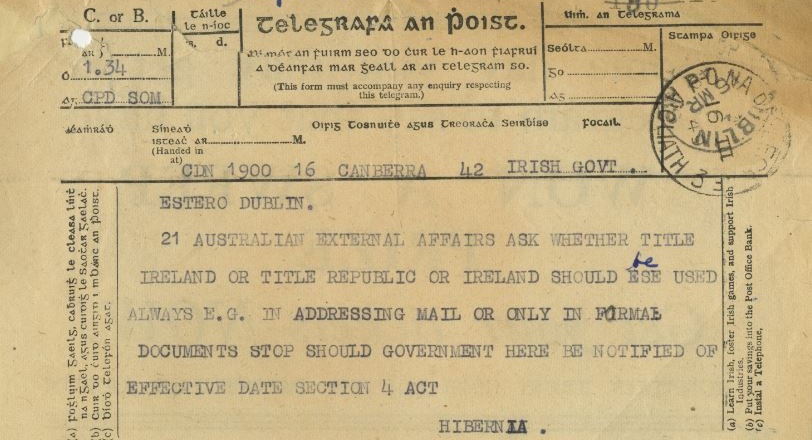

A telegram from the Irish embassy in Canberra to Dublin, seeking guidance on how best to formally describe the Irish state given the imminent change in its constitutional status, March 1949 (UCDA P104/4443).

A telegram from the Irish embassy in Canberra to Dublin, seeking guidance on how best to formally describe the Irish state given the imminent change in its constitutional status, March 1949 (UCDA P104/4443).

The British were shocked by Costello's decision and considered taking punitive action against the Irish government. If Ireland was leaving the Commonwealth, why should the privileges of membership be extended to the people of what would be (in the parlance of our own times) a 'third country'? This was the issue that Pakistan was apparently concerned about. It was particularly ironic that such questions were being raised just as the British recognised that a nationalist leader with whom they had long been at loggerheads had devised an instrument that could be used to maintain Commonwealth cohesion as newly independent states emerged in Asia and Africa.

Imperial and Commonwealth historians have begun to acknowledge, even if in a cursory manner, that de Valera’s concept of 'external association' had a resonance far beyond Ireland. The New Zealand historian W.D. McIntyre, for example, acknowledged the direct impact de Valera had in keeping India in the Commonwealth in 1949. India, Pakistan and Ceylon’s desire to remain in the Commonwealth, notwithstanding their new republican status, led to sustained efforts at the 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Meeting to find a way forward. The final wording of the 1949 London Declaration issued by the meeting stated that ‘The king remained symbol of the free association of the member nations and “as such head of the Commonwealth.”’ To accommodate India as a republic, the concept of allegiance to the Crown was suddenly dropped in favour of recognizing its wearer as ‘head of the Commonwealth’. This would have been unimaginable in the pre-war years and resulted in a scramble to gain credit for having come up with the final compromise. Those involved included Lester Pearson of Canada, Pakistan’s Zafrullah Kahn and India’s Krishna Menon; but McIntyre concluded that the formulation: ‘neatly incorporated the two concepts of symbol and head that de Valera had mooted back in 1921'. It was a fact that had been recognised by the British for some time; its public pronouncement came weeks after Ireland became a republic on 18 April 1949.

De Valera later told Nicholas Mansergh that the solution found for India in 1949 would have suited Ireland and could have paved the way for an Ireland within the Commonwealth. Whether this in turn could have facilitated Irish reunification, however, is another question. As for Ireland's new status as a republic, he argued that since the adoption of Bunreacht na hÉireann in 1937 Ireland was substantively a republic anyway, and thus implied that he and his party had done most of the heavy lifting over a decade earlier.

What is certain was that de Valera’s concept of external association assisted the evolution of the modern Commonwealth. As former colonies of Britain achieved independence, most chose to retain their previous links with Britain through Commonwealth membership. In 1949 there were eight members of the Commonwealth, today there are fifty-three.In Ireland external association has often been viewed in a negative light, and even de Valera himself dubbed it ‘the idea that failed’. But both the British and many of those who comprised the post-war Commonwealth concluded that this much-derided Irish construction offered a constitutional formula that could keep newly independent colonies within the Commonwealth, the maintenance and cohesion of which (especially in Asia) was deemed essential to Britain as the Cold War began.

The British responded to Ireland’s departure from the Commonwealth with the Ireland Act of 1949, which stated Ireland would not be treated as a ‘foreign country’ and confirmed the rights of Irish citizens to travel and work in the UK, thus confirming the Pakistani concerns that Dulanty had passed on to Boland in January of that year. These concessions only came about as a result of pressure exerted on Britain from other Commonwealth countries with large Irish Diasporas: Canada, Australia and New Zealand. But there was a sting in the tail: the Ireland Act also, for the first time, established that the status of Northern Ireland as part of the UK would only ever change with the consent of its inhabitants.

On the other side of the world, India seemed to implicitly concur with the view of both de Valera (who felt Costello had acted in haste) and those British officials who had recommended that they examine the External Relations Act that Costello had repealed; when India became a republic in 1950, it remained withinthe Commonwealth and arguably declined to follow the Irish example. The declaration of the republic in 1949 went hand in hand with a decision to leave the Commonwealth; the ramifications of that decision resonate not just in Ireland, but around the globe to the present day.

John Gibney is Assistant Editor with the Royal Irish Academy's Documents on Irish Foreign Policy (DIFP)series. Kate O'Malley is Managing Editor of the Royal Irish Academy's Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB). This blog was originally published on UCD Cultural Heritage Collections.

Explore the DIFP/UCD Archives online exhibition Republic to republic: Ireland's international sovereignty, 1919-1949.

Further Reading:

W.D. Mclntyre, The Britannic Vision: Historians and the making of the British Commonwealth of Nations, 1907-48(Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Diana Mansergh (ed.), Nationalism and Independence: Selected Irish Papers by Nicolas Mansergh(Cork University Press, 1997).

Deirdre McMahon, ‘Ireland and the Empire-Commonwealth’, in The Oxford History of the British Empire, Volume IV: The Twentieth CenturyJudith Brown and Wm Roger Louis (eds), (Oxford university Press, 1999).

Kate O’Malley, ‘Ireland and India: Post-independence Diplomacy’, in Irish Studies in International Affairs, Vol. 22 (Royal Irish Academy, 2011), pp. 145-162.

Cover image: 'Dev's boots', by Morgan O'Regan. All other images courtesy of UCD Archives.