An Irish envoy to revolutionary Russia, 1921

13 September 2018Who was Patrick McCartan, and why did Dáil Éireann send him to Russia during the War of Independence?

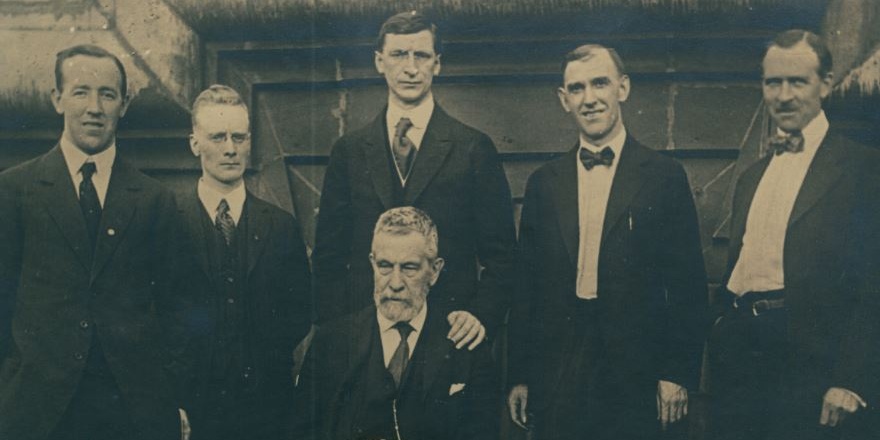

In the years after the Easter Rising, as Sinn Féin rapidly became the leading Irish nationalist party, the burgeoning Irish independence movement sought to exploit the turbulence of international affairs to their advantage. This took the form of lobbying the post-war peace conference to recognise Irish independence, trying to influence key constituencies (such as Irish America) to put pressure on their respective governments and distributing propaganda to bring international pressure to bear on the British. In the process, Sinn Féin assembled a range of emissaries and agitators who acted as de facto diplomats. One of them was Patrick McCartan, and in 1921 he sought to persuade the leaders of revolutionary Russia to recognise the Irish republic. His is pictured to the right of Éamon de Valera above; the others in the picture are (from left to right) Harry Boland, Liam Mellows, and Diarmaid Lynch, with John Devoy seated in the foreground.

McCartan was born into a farming background in Tyrone, and like many young nationalists claimed to have been radicalised by the centenary of the 1798 rebellion. While working as a barman in Philadelphia he joined the Irish-American republican group Clan na Gael, and after returning to Ireland to enrol as a medical student he also joined Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). He was very active in the latter and rose to become a member of the IRB supreme council in the run-up to the Easter Rising. The confusion over Eoin MacNeill’s attempts to call off the Rising meant that McCartan did not fight in it, though he was forced on the run in its aftermath and was briefly imprisoned in 1917.

As the photograph above testifies, McCartan was acquainted with many iconic figures in the independence movement in Ireland and overseas. In 1917, at the suggestion of the IRB, McCartan had been prepared to travel to Russia to explore the prospect of getting the Bolsheviks to recognise Irish independence. He was directed to return to the US instead, and despite being arrested with Liam Mellows while preparing to travel to Germany from Nova Scotia on a gun-running mission, McCartan remained in the US during Éamon de Valera’s American tour in 1919-20 tour.

McCartan later claimed to have continued to press the idea of reaching out to Russia on de Valera. It was not until late in 1920, when it was obvious that Sinn Féin’s approaches to the Paris peace conference and the Wilson administration had failed, that McCartan was eventually sent to Russia by a reluctant de Valera in a last-ditch effort to gain any kind of international recognition for an Irish republic. In the end no specific mission was entrusted to McCartan; he was sent merely to represent the republic. McCartan himself felt that the time to reach out to Russia had passed, but he went regardless, and left two lengthy and fascinating accounts – published in DIFP I - of both his attempts to secure Bolshevik recognition for Irish independence, and his own impressions of life in Russia amidst the turmoil of the Russian civil war.

McCartan was a reluctant supporter of the 1921 Treaty and, disillusioned in the aftermath of the civil war, moved to New York to resume his medical career. He chaired the committee that presented the Sam Maguire cup to the GAA in 1928, became a close friend of W.B. Yeats, returned to Ireland in 1937 and later became a founding member of Clann na Poblachta (incidentally, his only daughter married Ronnie Drew of The Dubliners). McCartan died in 1963 but his mission to Moscow remains relatively unknown. The emergence of Stalinism and the anti-communism evident in the early phases of the Cold War meant that by the later 1940s and 1950s, there was no eagerness on his part to promote or even to revisit his Russian affair (by way of contrast, in 1932 he had published a memoir entitled With de Valera in America). While he provided a copy of his 1921 reports as part of the statement he submitted to the Bureau of Military History (complete with extra details on ‘Foreigners in Moscow’) he offered no new reflections or considerations three decades later. The story of the Russian revolution has been told countless times, but the early years of Bolshevik rule were marked by some intriguing interactions between Russia and the west. While their engagement with Irish nationalists was minimal, the little-known story of McCartan and his eventual trip to Moscow forms a small but captivating part of this revolutionary tale; one best revealed in his own words.

Image reproduced by kind permission of UCD Archives.