New exhibition on Joseph Walshe (1886-1956): the founding father of the Irish foreign service

13 February 2019The second of the monthly exhibitions we are co-curating with the National Archives of Ireland deals with the lengthy career of the founding father of the Irish diplomatic service.

The second of our monthly exhibitions we are co-curating with the National Archives of Ireland is now on display there, and deals with the lengthy career of the man who essentially created the post-independence Irish diplomatic service. Joseph P. ‘Joe’ Walshe (1886–1956) was born in Tipperary. A former Jesuit seminarian and a solicitor by training, the Francophile Walshe served on the Dáil Éireann delegation to the Paris Peace Conference before returning to Dublin in 1922 to head the Irish Free State’s newly constituted Department of External Affairs (today’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). He was Secretary (we would now say Secretary General) of the Department of External Affairs from 1922 to 1946 and was largely responsible for constructing an embryonic diplomatic service from the disarray of the Treaty split (you can read a full account of his life in the Dictionary of Irish Biography). He is pictured above In Vatican City (in centre wearing papal insignia,with his colleague Nicholas Nolan to his left) following his appointment as ambassador to the Holy See after the Second World War.

The documents in our new exhibit touch upon some aspects of his varied career at the head of a government Department whose very existence and necessity was being questioned in the 1920s until Walshe was officially confirmed as its head in 1927 (prior to his he had merely been ‘Acting Secretary’).

In 1932 Walshe was worried lest his association with the outgoing Cumann na nGaedheal administration would lead to his dismissal by their successors in Fianna Fáil. He moved to convince Éamon de Valera of his loyalty, including, it was rumoured, by attending the same church for daily mass.

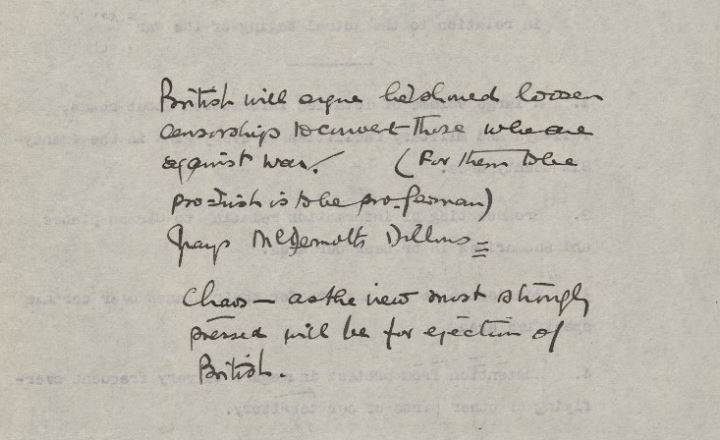

Walshe became a crucial adviser to de Valera in his recasting of Anglo-Irish relations throughout the 1930s, and especially during the Second World War. Ensuring Ireland’s neutrality during the ‘Emergency’ was the biggest test of an independent Irish foreign policy since independence in 1922. Working closely with de Valera, Walshe was at the heart of the most secretive aspects of wartime Irish foreign policy. The exhibition includes what is arguably one of the most significant documents in the history of Irish foreign policy: a May 1941 memorandum, annotated by Walshe, detailing the level of Irish co-operation with the Allies during the war. Equally, a 1942 note from Walshe to his friend and counterpart in the Department of Industry and Commerce, John Leydon, shows their difficulties in dealing with David Gray, the United States Minister in Dublin, who was an implacable opponent of Irish neutrality.

Some of Walshe's annotations to the May 1941 memorandum on Irish co-operation with the Allies.

The personal and professional summit of Walshe’s diplomatic career was his appointment as Ireland’s Ambassador to the Holy See in 1946; he was a devout Catholic who placed the Catholic Church and the Holy See not only at the centre of Irish foreign policy, but also at the centre of global affairs. It was the first time an Irish diplomat had been appointed at this level, an ambassador being the highest diplomatic appointment. That Ireland’s first ambassador would be appointed to the Holy See was indicative of where the Catholic Church fitted into Walshe’s view of Irish foreign policy; a view that was reciprocated, as revealed in a note from the Apostolic Nuncio in Ireland to Taoiseach John A. Costello following Walshe’s death in February 1956.

Walshe died in Egypt whilst returning from a trip to South Africa and is buried in Cairo. Like many public servants, he resolutely declined to set down his personal recollections of his career; his legacy is as the founding father of the Irish foreign service.

The documents mentioned above are now on display until 28 February 2019 in the lobby of the National Archives of Ireland, Bishop Street, Dublin 8, which is open from 9.15am to 5pm Monday to Friday.

Images courtesy of National Archives of Ireland.