In pursuit of Arthur Brownlow’s Irish manuscripts

03 February 2021Library Blog post. Dr Bernadette Cunningham traces some of the Irish manuscripts seen by Edward Lhuyd, Welsh antiquary and lexicographer, in 1699 when he visited Arthur Brownlow of Lurgan, County Armagh.

Long before I came to work in the library of the Royal Irish Academy, I was a registered reader there. I was able to visit on my mid-week half-days off from the library in which I then worked. My 1980s visits were to the same early Victorian Reading Room in use today, though I recall worn linoleum on the floor, wooden stands for the manuscripts and minimal heating. Some things have changed.

A recent invitation to speak at an event organised as part of the Lurgan Townscape Heritage scheme (a project of Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council) has reminded me that among the Academy manuscripts that were relevant to my research in the mid-1980s were those for which a link could be established back to Arthur Brownlow (d.1710), landlord of Lurgan, County Armagh, in the late seventeenth century.

At the time, this was a spin-off from my husband’s work on editing Arthur Brownlow’s lease book, preserved in Armagh County Museum. In the way that one historical puzzle always seems to lead to another, we became interested in researching every aspect of Brownlow’s background. The research led to one of many joint articles we have published since then.

Arthur Brownlow had come to the attention of the Welsh antiquary, Edward Lhuyd (1660–1709), during his visit to Ireland in 1699/1700. Lhuyd was collecting manuscripts to assist in his study of Celtic languages, and purchased some twenty or thirty Irish manuscripts while in Ireland. Among those who sold manuscripts to him was Eoin Ó Gnímh in County Antrim, a descendant of a family of professional Gaelic poets. The Welshman also went to Fenagh, in County Leitrim, where he met with Tadhg Ó Rodaighe, who had a collection of twenty law manuscripts but was not prepared to sell.

Rather more surprising is that Edward Lhuyd also visited Arthur Brownlow, a man of settler origin in Lurgan, County Armagh. Lhuyd must have been told that a visit to Lurgan would give him the opportunity to see some Irish manuscripts, so Brownlow must have enjoyed a reputation as a collector.

It transpired that Arthur Brownlow had at least twelve Irish manuscripts. He also had some in Latin that Lhuyd was less concerned to describe. It was not a large collection but twelve Irish manuscripts as compared with Tadhg Ó Rodaighe’s twenty was still impressive. Just like Ó Rodaighe in Leitrim, Brownlow did not sell his Irish manuscripts to Lhuyd. Their value to him was not a monetary value.

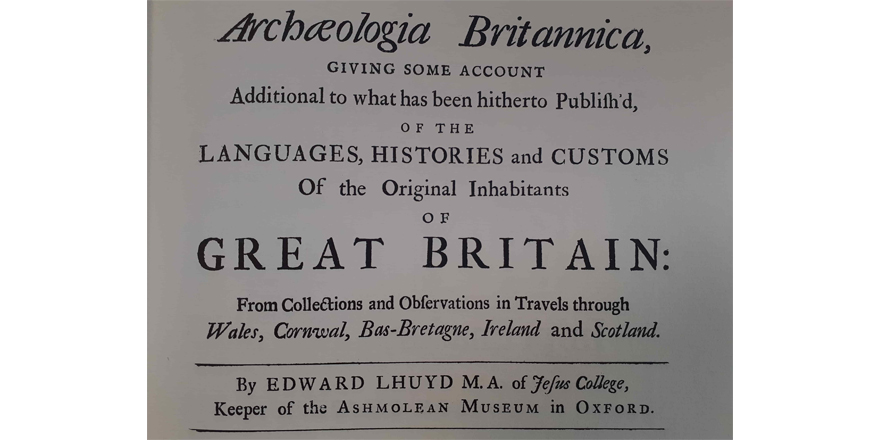

Edward Lhuyd’s catalogue of Brownlow’s Irish language manuscripts was published in 1707. Excluded from Lhuyd’s list, probably because it was in Latin rather than Irish, was an early ninth-century vellum manuscript now known as the Book of Armagh. This was a Gospel book, roughly contemporary with the more famous Book of Kells. In addition to New Testament texts, the Book of Armagh also contains material dating from the seventh century relating to St Patrick, and these were later used to assert the primacy of Armagh. Brownlow was probably interested in the manuscript primarily because of its local association with Armagh. The Brownlow family retained the Book of Armagh until 1853 when they sold it to William Reeves. He passed it to John George Beresford, archbishop of Armagh, who presented it to Trinity College, Dublin, in 1854 (TCD, MS 52).

Title page of Edward Lhuyd’s Archaeologia Britannica (1707).

Brownlow owned a copy of Geoffrey Keating’s manuscript history of Ireland, known as Foras feasa ar Éirinn. Although translations into English and Latin were in circulation in manuscript in Brownlow’s lifetime, Brownlow chose to acquire an Irish language copy. None of the copies preserved in modern archives, however, has been positively identified as the one he owned. In 1696 he may have permitted another Lurgan resident, Patrick Logan, to have a copy made (now National Library of Scotland, Advocates MS 33/4/11). Patrick Logan was a Quaker schoolmaster, originally from mid-Lothian, and although he could not read Irish he had a particular interest in the history of the early kingdoms of Ireland and Scotland.

Brownlow also owned a transcript of the Book of Invasions, Leabhar Gabhála Éireann, as revised in 1631 by a Franciscan historian, Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, at Lisgoole, County Fermanagh. This was a medieval legend of the peopling of Ireland, describing the successive waves of settlers that had come to the island of Ireland in prehistoric times. In Brownlow’s day, it would have still been regarded as largely historical rather than mythical. The seventeenth-century copy that he owned has not been identified.

Edward Lhuyd’s list of Brownlow’s Irish manuscripts also mentioned:

‘A copy of the Leabhar Eghonagh, or a treatise of the reigns of the family of the O Neilles...; three books of miscellanies containing several ancient poems or Dáns and some fragments of history and chronology; Cath Mhuileana ... a Romance; Buille Shuibhne, or Suibhne's distraction. A Romance; Comhrac Fhirdhia 7 Cconluinn or the Conflict of Ferdia and Conlin. A Romance; Cath Comhair, Cath Gabhra, Cath Code, Cath Atha Bo, Cath Ollarba, Battles fought by the Fion Erion or ancient Militia of Ireland, under Fion Mac Cual their great Commander’.

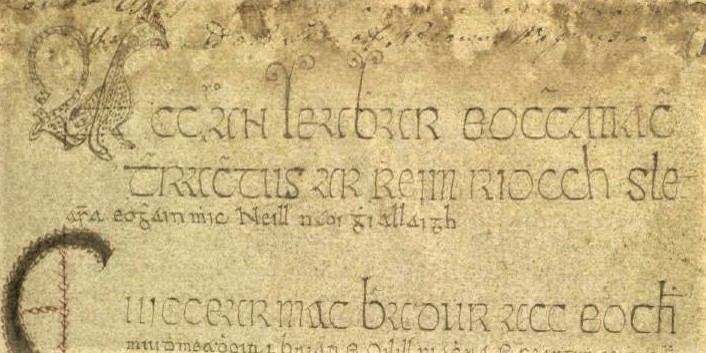

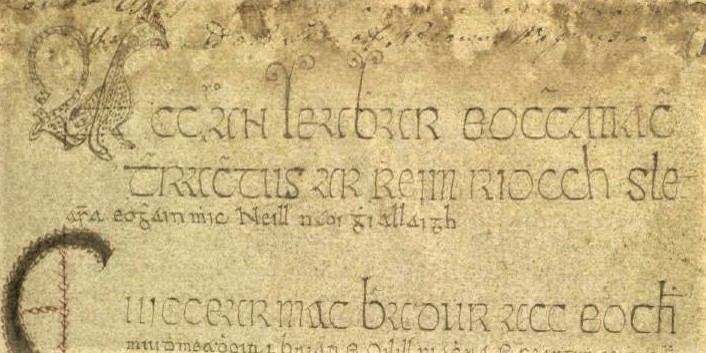

The Leabhar Eoghanach contains historical material, principally genealogical, on the O’Neills of Ulster, and traces their story back to their ancestor Niall of the Nine hostages reputed to have lived in the fifth century AD. The O’Neills had once occupied the lands which the Brownlow family acquired in County Armagh, and thus the Leabhar Eoghanach shed light on the kind of society that had existed in Armagh in earlier times, and helped explain the ongoing esteem in which the descendants of the O’Neills were held down to the late seventeenth century.

Opening of ‘An Leabhar Eoghanach’ a tract on the O’Neills in Leabhar Cloinne Aodha Buidhe. RIA, MS 24 P 33, p. 101.

Two transcripts of this text survive in a manuscript associated with the O’Neills of Clandeboy, now RIA, MS 24 P 33. It has been published in the Irish Manuscript Commission’s edition of Leabhar Cloinne Aodha Buidhe (Dublin, 1931), pp 1–40. The manuscript has an inscription in Irish in Arthur Brownlow’s own hand (p. 25), indicating his ownership on 1 August 1689:

‘Ag so leabhar Artuir Bhrounló nó Mach Ar[tuir] an céud lá do mhí na Lughnasa an bhliaghain ... 1689’.

Arthur Brownlow’s Irish signature, 1689, in Leabhar Cloinne Aodha Buidhe. RIA, MS 24 P 33, p. 25.

The same composite manuscript contains a significant collection of praise poetry in Irish, addressed to various Ulster chiefs. Most prominent among them were Arthur Brownlow’s neighbours, the O’Neills of Clandeboy.

Another book of miscellanies in the Royal Irish Academy has the name William Brownlow on the second page (probably Arthur’s son rather than his grandfather). This manuscript, now RIA, MS 24 P 13, was written in 1621 by Luan Taidg for Niall Ó Cionga (King). It contains poetry, a genealogical tract, a list of kings, and a corrupt version of the medieval place-lore text known as the Dinnsheanchas. The ‘very ancient treatise of geography’ as listed by Edward Lhuyd was probably a version of the Dinnsheanchas, and might be the copy found in this manuscript. Likewise, the ‘treatise of monarchs of the world’ might possibly be the list of kings also noted in the same manuscript.

Signature of William Brownlow from RIA, MS 24 P 13.

In the late nineteenth century these two composite manuscripts dating from the seventeenth century and formerly owned by the Brownlow family came into the possession of Maxwell Close, a Church of England clergyman based in Ireland. Revd Close then sold them to William Reeves, church of Ireland bishop of Down, Connor & Dromore, and former keeper of the Armagh Public Library, now known as the Robinson library.

The two manuscripts, now with the shelfmarks 24 P 33 and 24 P 13, were part of the Reeves collection purchased at auction in 1892 by the Royal Irish Academy. William Reeves was President of the Academy at the time of his death in January 1892. William Reeves took an interest in the Brownlow connection, and he copied Edward Lhuyd’s list of Brownlow’s manuscripts into the first page of Leabhar Cloinne Aodha Buidhe.

Arthur Brownlow also had copies of specific Irish tales, and some were not just chance acquisitions. He commissioned a copy of the tale known as Cath Maighe Léna (The Battle of Magh Leana) in 1685, and paid Padraig Mac Óghanain to transcribe it. The manuscript he commissioned is now RIA, MS 24 L 36, as a scribal note on the first page indicates. It was purchased by the Academy along with other items in 1869 from John O’Daly, a Dublin-based book dealer and editor.

The tale of the battle of Magh Leana mainly relates to south Munster in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but it involved the triumph of Conn Céad Cathach over his rival Eoghan, the battle between Leath Cuinn and Leath Mogha, the northern and southern halves of Ireland, resulting in the triumph of the northerners. Such a story of northern success apparently appealed to Brownlow.

It is said that in the year 1700, Arthur Brownlow transcribed and translated an elegy on Eoghan Ruadh Ó Neill for his collection. The poem, entitled ‘Do chaill Éire a céile fírcheart’ [Ireland has lost its rightful spouse], had been composed by Fr Cathal (Tomás) Mac Ruaidhrí in the mid-seventeenth century. Versions of the English translation attributed to Brownlow are preserved in RIA, MSS 23 D 16 and 24 E 26.

Eoghan Ruadh Ó Neill had been an important military leader in the 1640s in Ireland, and died in 1649. His former territory was later occupied by Brownlow, and most of his military campaigns had been fought within a few miles of Brownlow’s property. Brownlow was interested in such people from the past, and he may have regarded Eoghan Ruadh as another local historical hero.

Even though Brownlow’s collection of Irish manuscripts was of modest proportions, it seems that he had acquired some of those highlighted here with a specific interest in mind. He assembled a collection of sources that would facilitate his study of the place in which he lived and the peoples who had lived there in the past and the stories that had been told about that place from time immemorial.

Those stories, and the lives of those peoples, were available in Irish only, the traditional language of that region. Arthur Brownlow, whose family were newcomers in County Armagh, embarked on a study of the language and the literature that would help him to become immersed in the ancient and modern history of the place he called home.

The afterlife of manuscripts – the uses to which they are put, and the myriad ways in which they change hands after they leave the hands of their scribes and first patrons – can become a large part of their story. The questions asked about those manuscripts change over time, so that the story of their owners can be of as much interest as the texts they contained. Brownlow’s attitude to the manuscripts he purchased or commissioned differed from that of William Reeves to those same manuscripts. The questions of interest to modern researchers are not necessarily those that would have interested either Brownlow or Reeves.

While some of the Irish manuscripts Arthur Brownlow owned in 1699 can no longer be identified, it is a testimony to the work of later collectors, not least those associated with the Royal Irish Academy in the nineteenth century, that enough had been preserved to make the visits of a young researcher to the Academy library in the 1980s seem worthwhile.

Bernadette Cunningham

Deputy Librarian

Further reading

Cunningham, Bernadette & Gillespie, Raymond, ‘An Ulster settler and his Irish manuscripts’, Éigse: Journal of Irish Studies, 21 (1986), 27–36

Cunningham, Bernadette & Gillespie, Raymond, ‘Patrick Logan and Foras feasa ar Éirinn, 1696’, Éigse: Journal of Irish Studies, 32 (2000), 146–52

Gillespie, Raymond (ed.), Settlement and survival on an Ulster estate: the Brownlow leasebook, 1667–1711 (Belfast: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, 1988)

Gwynn, John (ed.), Liber Ardmachanus: the Book of Armagh (Dublin, 1913)

Lhuyd, Edward, Archaeologia Britannica: an account of the languages, histories and customs of the original inhabitants of Great Britain, vol. 1. Glossography (Oxford, 1707; reprint Shannon, 1970) (archive.org)

Macalister, R.A.S. & Mac Neill, John (eds), Leabhar Gabhála: the book of conquests of Ireland. the recension of Micheál Ó Cléirigh (Dublin, 1916)

Ó Buachalla, Breandán, ‘Arthur Brownlow: a gentleman more curious than ordinary’, Ulster Local Studies, 7:2 (1982), pp 24–8

Ó Donnchadha, Tadhg (ed.), Leabhar Cloinne Aodha Buidhe (Dublin: Irish Manuscripts Commission, 1931)

RIA, MS 67 E 4: Case catalogue of MSS in the Royal Irish Academy and lists of the Reeves and Gavan Duffy collections in the Royal Irish Academy

RIA, MS 24 P 33 (Leabhar Cloinne Aodha Buidhe): digital version available: isos.dias.ie

Trinity College, Dublin, MS 52 (Book of Armagh): digital version available. digitalcollections.tcd.ie