Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks: Patrick Kavanagh

16 May 2015Patrick Kavanagh, The Great Hunger, 1942

This week’s Modern Ireland in100 Artworks features Patrick Kavanagh’s The Great Hunger.

Kavanagh was the first English language poet of real stature to emerge from what Fintan O Toole describes as a class that was up until 1942 much written about by others: the Catholic Small farmers who were the heart of independent Ireland.

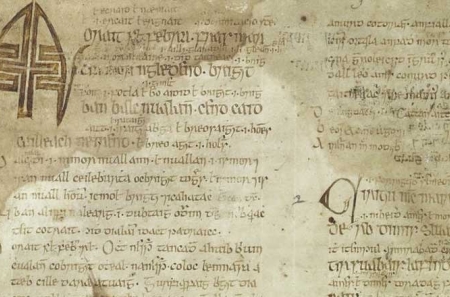

Much of The Great Hunger was published, on the recommendation of John Betjeman, in the London journal Horizon in 1942, before the full poem was printed, in a limited edition, by the Yeats family’s Cuala Press, in Dublin, later that year.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography features an entry on the poet. Read about him below:

Patrick Joseph Kavanagh, by Antoinette Quinn

Kavanagh, Patrick Joseph (1904–67), poet, novelist, and journalist, was born 21 or 23 October 1904 at the family home in the townland of Mucker, Inniskeen parish, Co. Monaghan, the elder son and fourth of ten children of James Kavanagh, cobbler, and his wife, Bridget (née Quinn) of Corcreagh, Co. Louth, barmaid, daughter of an agricultural labourer and subsistence farmer.

Education and early life Kavanagh was educated at Kednaminsha national school in Inniskeen (1909–17), when he left to be apprenticed in his father's trade and to help on the nine acre farm his parents had bought in 1910. The cobbling business was dwindling into a repairs-only trade in the 1920s, and in 1925 the Kavanaghs bought a sixteen-acre farm a few miles from Mucker, referred to by Patrick in the poem ‘Art McCooey’ as ‘my foreign possessions in Shancoduff’.

In the years before his father's death in 1929 Patrick gradually took over his work, doing some cobbling as a sideline but mainly running the two small farms under the direction of his managerial mother. Like the elder sons of neighbouring farmers, working for a pittance in fields that they expected one day to inherit, he attended weekly mass, bought and sold at fair and market in the nearby towns of Carrickmacross and Dundalk, and spent his few leisure hours playing Gaelic football or pitch and toss or attending dances, wakes, and weddings. Unlike them, however, he was writing poetry from his early teens, copying the patriotic and sentimental ballads sold on coloured sheets at fairs or to be found at the back of Old Moore's Almanac. Inniskeen already had a practising ballad maker, John McEnaney, known as the ‘Bard of Callenberg’. Ambitious of being more than a local balladist, Kavanagh was also studying and trying to imitate the poems he found in schoolbooks and in Palgrave's Golden treasury of English poetry.

Literary beginnings Kavanagh was almost twenty-one when, riffling through the papers at a newsagent's shop during an August market in Dundalk, he came upon the Irish Statesman, the weekly journal of arts and ideas edited by George Russell (qv), and discovered the existence of other contemporary poets. This journal became his artistic manual. By the end of 1929 he could write brief nature lyrics with a religious inflection that were acceptable to Russell, and three of his poems were published in the journal, among them ‘Ploughman’. When the Irish Statesman closed in April 1930, Kavanagh became a regular contributor to the quarterly Dublin Magazine and his poems also began to appear in English journals. His first visit to Dublin in December 1931 was to make an unannounced call on George Russell, who plied him with books and advice. Emphasising his role as ‘ploughman’, he had walked to Dublin wearing his shabby work clothes rather than take the train. From then on he often visited the city to meet other writers and seek literary stimulus. A farmer–poet was an exotic figure in Dublin's literary circles and he received a great deal of encouragement and kindness. Kavanagh's first collection, Ploughman and other poems, published in London by Macmillan in 1936, includes his best early poem, the sonnet ‘Inniskeen Road, July evening’, a wry reflection on the anomaly of a village poet. For the most part his brief lyrics, written in a decorously pastoral vein and suffused with religious imagery, ignored the inelegant realities of his farming milieu.

When his first book brought about no change in his life as full-time farmer and spare-time poet Kavanagh decided in May 1937 to try his fortune in London. Here he was commissioned to write The green fool (London, 1938), an autobiography combining a portrait of the artist with a portrait of his local community. A comic realist yet lyrical account of his life in Inniskeen, the book revealed Kavanagh's ability to project an enduring narrative persona and it was enthusiastically reviewed both in London and Dublin. It was withdrawn in 1939 when Oliver St John Gogarty (qv) prosecuted a successful libel suit against Kavanagh and, despite the favourable reception of the stubbed version in New York, was never reprinted in Kavanagh's lifetime. By the late 1940s he had come to dislike The green fool and refused permission to republish it. Nevertheless, the mandate to describe life in his small-farm community changed the course of Kavanagh's writing, compelling him to attend to the subject closest to him, which he had hitherto disregarded as being unworthy of literary treatment.

This new direction was reinforced when, unable to earn a livelihood in London, he moved to Dublin in August 1939. Although he intended his stay there to be a brief interlude before settling in London, the outbreak of the second world war left him stranded and, except for short intervals spent in Inniskeen, London, and New York, he was to be a Dublin-based writer for the remainder of his life. At first he came under the influence of Sean O'Faolain (qv) and Frank O'Connor (qv), who were engaged in a literary programme of documenting and criticising the Irish state. Kavanagh ceased writing for the Dublin Magazine in 1940 and instead contributed to The Bell, a new Irish monthly launched in October of that year with O'Faolain as editor and O'Connor as poetry editor. The novel he wrote under their aegis, about the disenchantments of a young farmer with literary pretensions, proved unpublishable in its early 1940s drafts. However, his new focus in poetry on his country childhood and life as a farmer resulted in several memorable short lyrics, including ‘A Christmas childhood’, ‘Art McCooey’, ‘The long garden’, and a poem of 759 lines, The great hunger (Cuala Press, Dublin, 1942), widely regarded as one of the twentieth century's finest long poems.

The great hunger In the 1960s Kavanagh was to repudiate The great hunger because of its tragic approach and its sociological concern with the woes of the poor, but the poem's portrayal of the day-to-day circumstances and the religious and sexual psyche of an elderly bachelor farmer, Patrick Maguire, brings a world to vivid and prolific life in clear, sharply realised images. The great hunger describes a small-farm ethos in which a puritanical catholicism and a preoccupation with economic security combine to render men's and women's lives joyless and emotionally, sexually, and spiritually unfulfilled. Patrick Maguire is presented as a typical Irish farmer, sacrificing himself body and soul to agricultural productivity, living ‘that his little fields may stay fertile’, a human tragedy repeated ‘in every corner of this land’. Yet he also transcends his exemplary status to become a rounded character. The great hunger broke new ground thematically and ideologically at a time when poetry still tended to idealise country life. Technically it was equally daring: written in a mixture of free-verse paragraphs and rhymed stanzas, it deployed the cinematic strategies of zoom and montage in its depiction of locations and characters. Although some critics were uncomfortable with its innovative techniques and disruption of literary pieties, The great hunger established Kavanagh as a powerful voice in Irish writing. It was quickly followed by a second long poem, Lough Derg, first published posthumously in 1971 and, in 1978, in book form (Martin, Brian, & O'Keeffe, London; Goldsmith Press, the Curragh, Ireland). This poetic documentary on a three-day pilgrimage to St Patrick's Purgatory in Co. Donegal, an anatomy of Irish catholicism, was technically similar to The great hunger but was not as focused, detailed, or controlled. After it, Kavanagh abandoned the long poem.

Dublin writer In Dublin, Kavanagh eked out a precarious living as a freelance journalist, writing occasional features and book reviews for the three daily newspapers, the Irish Times, the Irish Independent, and the Irish Press. He contributed a twice-weekly gossip column to the Irish Press under the penname ‘Piers Plowman’ (September 1942 to February 1944) and a book review column to the catholic weekly The Standard (February to June 1943). He was a staff reporter on The Standard (August 1945 to 1947) and also its film reviewer (February 1946 to July 1949).

A morning writer who spent the rest of the day on the move, Kavanagh soon became established as ‘a character’, a countryman-about-town: tall, thin, shabbily dressed, wearing a battered hat and thick horn-rimmed spectacles, walking like a ploughman, and speaking in a pronounced south Monaghan accent. While enjoying his own notoriety, he resented the intrusive familiarity and condescension which it elicited and cultivated a gruff rudeness to ward off unwanted company. An endearing and entertaining companion to those he befriended, he was given a wide berth by many Dubliners and fellow writers, who dreaded his abrasive manner and rough tongue. As the years passed without bringing the permanent and pensionable white-collar job he longed for to relieve him of hack journalism, he grew embittered, feeling that his genius was unrewarded and unappreciated. State or corporate patronage for writers was then unknown and, despite a succession of romantic attachments, Kavanagh's dream of solving his financial difficulties by marriage to a rich woman eluded him. He craved economic security but was destined to spend most of his writing career living hand to mouth, his meagre earnings depleted by an addiction to cigarettes and, from 1950, to gambling on horses and, later, by a growing dependence on alcohol. Well-disposed Dubliners treated the impoverished writer to meals and drinks and gave small donations, as much as they could afford in the 1940s and 1950s when there was little affluence.

Kavanagh's literary reputation was much enhanced by the publication of his second collection, A soul for sale (Macmillan, London, 1947), through which The great hunger, previously available only in an expensive limited edition, became widely known, and also by Tarry Flynn (Pilot Press, London, 1948). This, the final draft of his much revised novel, was an affectionate, and humorous account of a poet–farmer's life in a country parish, which was to acquire classic status and be often republished and reissued from the 1960s. While it was admired from the outset the publisher's bankruptcy in 1949 meant that it soon became unavailable.

Satire and sonnets From the mid 1940s Kavanagh had begun to satirise Dublin culture in a series of poems, verse playlets, and essays. Most of these were concentrated in two monthly magazines, The Bell between 1947 and 1955 and a new avant-garde arts magazine, Envoy (December 1949 to July 1951), to every issue of which he contributed a column entitled ‘Diary’. One target of Kavanagh's satires and social criticism was the undiscriminating Irish bourgeoisie who liked to fraternise with artists, actors, and writers but was incapable of recognising or supporting real talent. The principal and relentless object of his scorn was the contemporary cult of Irish ethnicity in the arts and media, particularly in literature. Above all, the use of Irishness as an aesthetic criterion was anathema to him – so much so that he repeatedly declared, ‘Irishness is a form of anti-art.’ His hostility to the Fianna Fáil government and to the smug, chauvinistic mindset he found endemic in Ireland was given free rein in the thirteen-week run of the magazine Kavanagh's Weekly (12 April to 5 July 1952), which he wrote with his brother, Peter. This Weekly irritated and alienated so many influential persons and institutions that after its closure he was virtually unemployable in Ireland.

Kavanagh wrestled with his own proclivity for satire and condemnation, perceiving it as spiritually corrosive and inimical to lyricism: ‘But satire is unfruitful prayer’ (‘Prelude’). This interior struggle became the theme of early 1950s self-admonitory poems such as ‘Auditors in’ and ‘Prelude’. In other fine lyrics from these years – ‘Ante-natal dream’, ‘Kerr's ass’, ‘Innocence’, ‘Epic’, ‘On reading a book on common wild flowers’ – he ponders the imaginative sources of his poetry. Another new poetic theme was a rueful yet unsparing self-portraiture in ‘Bank holiday’, ‘I had a future’, and ‘If ever you go to Dublin town’, as well as in parts of ‘Auditors in’ and ‘Prelude’.

Kavanagh's life reached a nadir between spring 1954 and spring 1955. Attracted by the prospect of a financial windfall, in February 1954 he took a very stressful high court libel action, which he initially lost. By the time he had won the right to appeal against the verdict in March 1955 he was suffering from lung cancer, an illness that inspired one of his best sonnets, ‘The hospital’. While the operation to remove a cancerous lung was successful he never recovered his former robustness and for the remainder of his life was increasingly plagued by health problems. Two years after his convalescence he enjoyed a few months of lyrical renewal when he produced a series of sonnets and couplet poems that celebrated and blessed ordinary urban and rural sights and sounds in a style that combined argot, cliché, and comic rhyming with meditative insights and religious rapture. Among the best known of these are the sonnets ‘October’, ‘Question to life’, and ‘The one’, and two sonnets commemorating his summer convalescence in 1955, ‘Canal bank walk’ and ‘Lines written on a seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin’. These were collected in Come dance with Kitty Stobling (Longmans, Green & Co., London, 1960), the Poetry Society's summer choice.

Last years and assessment An extramural lectureship in poetry at UCD from April 1955 was intended as a sinecure to ensure the poet a regular income, but he delivered a spring series of lectures on poetry for several years. He also contributed a weekly column to the Irish Farmers Journal (June 1958 to March 1963) and the RTV Guide (January 1964 to October 1967). Almost everything, a recording of the poet reading his own work, was first published by Claddagh Records, Dublin, in 1963. Collected poems (MacGibbon & Kee, London, 1964), a critical and commercial success, was followed by Collected prose (MacGibbon & Kee, 1967), and the dramatisation of Tarry Flynn at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, in November 1966 was a box-office hit. ‘On Raglan Road’, written in 1946 but collected for the first time in Collected poems and popularised by Luke Kelly (qv) of ‘The Dubliners’, became one of the best-known Irish songs. Despite failing health and declining productivity Kavanagh was by now Ireland's unofficial poet laureate, lionised by young poets and students.

On 19 April 1967 he married Katherine Barry Moloney, with whom he had enjoyed a seven-year relationship in London, in the Church of the Three Patrons, Rathgar, Dublin, her family's parish church. Her father was a pharmacist; both her parents had been republican activists in the war of independence and her mother was a sister of the famous revolutionary Kevin Barry (qv).

Patrick Kavanagh died of pneumonia in a Dublin nursing home on 30 November 1967. He was buried at Inniskeen. In Ireland Kavanagh's posthumous literary reputation was sustained by numerous reprintings of Collected poems (1964) throughout the 1970s and 1980s and by the inclusion of his poems in the leaving certificate poetry anthology, Soundings (edited by Augustine Martin (qv)), from 1970 to 2000. It gained momentum from 1996, when the issue of copyright was clarified by the Irish courts. After that The green fool and Tarry Flynn remained continuously in print; Selected poems (London, 1996) was followed by A poet's country: selected prose (Dublin, 2003) and a new edition of Collected poems (London, 2004). Many Irish poets are Kavanagh partisans; his poetry generates much criticism and discussion; he has been promoted as a Roman catholic writer and thinker; and he is a favourite with the general reader. Outside Ireland, particularly in the USA, it is quite otherwise. In spite of the best efforts of Irish poets and the repeated championship of the Nobel laureate, Seamus Heaney, Patrick Kavanagh is almost unknown. In so far as he is read, it is as the author of Tarry Flynn rather than as one of Ireland's leading poets.

The principal archive of Kavanagh's papers is in the library of UCD; the Harry Ransome Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and the National Library of Ireland also have significant manuscript holdings and the latter has a collection of photos by Elinor Wiltshire. A granite seat in the poet's honour, on the bank of the Grand Canal near Baggot Street Bridge, was unveiled in March 1968; John Coll's life-size bronze sculpture of the poet sitting on a bench on the opposite bank dates from 1991. There are portraits by Edward McGuire (qv), Patrick O'Connor (qv), Micheal Ó Nualláin, Seán O'Sullivan (qv), and Patrick Swift (qv) (both lithograph and oils), and a sculpted head by Desmond MacNamara. Photographs, in addition to Elinor Wiltshire's, include one by Bill Brandt and one by Evelyn Hofer. A detail from John Skelton's posthumous portrait, based on Hofer's 1967 photo, was adopted as the logo of the Patrick Kavanagh Centre, Inniskeen, and as the basis of the commemorative centenary stamp issued by An Post, Ireland, in 2004. Films include Self portrait (1962), a talk to camera by Kavanagh, produced by Telefís Éireann, A film profile of Patrick Kavanagh (1966), directed for Telefís Éireann by Adrian Cronin, Where Genesis begins (1978), directed by Bill Miskelly, and Patrick Kavanagh – no man's fool (2004), directed by Sé Merry Doyle.

Read the Irish Times article in full.