Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks: Irish Pavilion, New York World’s Fair

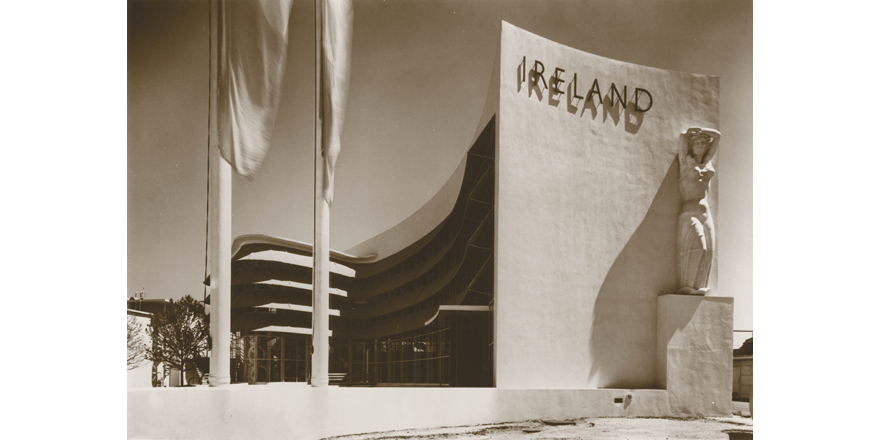

25 April 2015Irish Pavilion, New York World’s Fair, 1939 by Michael Scott

Catch up on all of the Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks features.

The 1939 entry in the Ireland in 100 Artworks series is the Irish Pavilion for New York World’s Fair by Michael Scott. The exhibition which opened in Flushing Meadows under the theme ‘a new world of tomorrow’ and the aspiration of a ‘fuller, happy existence for the average man’.

Patrick Scott was the designer behind the Irish Pavilion dubbed the Shamrock Pavilion because of its shape when viewed from above.

Speaking in her Irish Times article Catherine Marshall, editor of Volume V of the Art and Architecture of Ireland, spoke of it heralding ‘a growing sense of identity and independence’. ‘Despite Britain’s efforts to include Ireland under its banner, the country demanded and got its own space. Instead of the round towers, high crosses and thatched cottages inhabited by the “genuine” Irish craftworkers, musicians and dancers of previous international exhibitions, Scott went for broke with a thoroughly modern architectural showcase into which art, history and commerce were seamlessly integrated, a building in which the symbolic shamrock plan was elevated by a modernist cocktail of glazed curtain walls and clean white plaster.’

The choice of Michael Scott was controversial because he was chosen by Seán Lemass without the normal competition for a commission of such importance. But Scott saw it as an opportunity to show Ireland in a new and modern light. Read his entry in the Art and Architecture of Ireland.

Read more about the artist in the Dictionary of Irish biography entry below.

Read the Irish Times article in full.

What do you think of the building? Tweet us an let us know your thoughts on @RIAdawson

Michael Scott, by Lawrence William White

Scott, Michael (1905–89), architect, was born 24 June 1905 in Drogheda, Co. Louth, second child among two sons and two daughters of William Scott, a school principal and later schools inspector from Co. Kerry, and Hilda Scott (née Daly), native of Cork city. In his childhood the family moved to Dublin, settling on Leinster Rd West, Rathmines. His mother drowned in the river Dodder when he was fourteen.

Architecture and acting Educated by a private tutor and in several Dublin schools, Scott finished his secondary education at Belvedere College, where he played junior and senior schools cup rugby, and demonstrated talents in acting and painting. Though he contemplated a career as a painter, his father encouraged architecture as more financially secure. After training as an articled apprentice in the Dublin firm of Jones and Kelly (1923–6), he worked as an assistant in another private firm, and in the architects' department of the OPW. For several years he juggled architectural study and practice with his other interests. During his apprenticeship, he took evening classes at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, and enrolled as the first male student in the school of acting conducted at the Abbey theatre by Sara Allgood (qv). He acted in small roles at the Abbey, designed the conversion of part of the Abbey's premises into the small, experimental Peacock theatre (1926–7), and toured America in a six-month season of plays by Sean O'Casey (qv) (1927– 8), playing the lead role of Jack Clitheroe in the first New York production of 'The plough and the stars'. Starting his own architectural practice from a room in the family home (1928), he designed a new outpatients' wing for St Ultan's children's hospital (1928–9), having observed trends in hospital design while in America, at the request of Madeleine ffrench-Mullen (qv), secretary of St Ultan's. He converted the Rotunda supper-room and ballroom into the Gate theatre (1930). Acting the lead role in a London production (1929) of 'The new gossoon' by George Shiels (qv), he took the stage name 'Wolfe Curran' to conceal his absence from architectural clients in Dublin; drawing rave reviews, when his identity was revealed in the press, he withdrew and never again acted professionally.

Pioneering modernist Entering partnership with Norman Good (1931–8), Scott became a leading Irish exponent of the international style in architecture. Influenced chiefly by Le Corbusier, his early designs also exhibited a Dutch modernist inflection, especially in his penchant for curved bays, corners, and ends. He was instrumental in organising a lecture in Ireland by Walter Gropius, director of the Bauhaus, and one of the vanguard figures of the modernist movement (1936). Primarily involved in house and hotel design, the firm of Scott and Good executed two important commissions under the hospital building programme financed by the hospitals' sweepstakes. Offaly county hospital, Tullamore (1934–7), is a hybrid of art deco, the international style, and traditional styles, with rugged limestone walls, and the modernist horizontality of the elevation being modified by recesses and a curved central bay. Laois county hospital, Portlaoise (1933–6), is a more unabashedly modernist statement, with uninterrupted flat planes and white concrete walls, but effecting a sterile functionalism. The field of cinema architecture allowed Scott to practise a more exciting version of modernism, and he incorporated gleaming white walls and extensive glazing in his designs for Ritz cinemas in three provincial towns: Carlow (1937–8), Athlone (1938–9), and Clonmel (1939–40).

Scott made his name with two works of the latter 1930s, both landmarks of Irish modernism. The first was 'Geragh' (1937–8), the house he designed for himself on a rocky seaside promontory in Sandycove, Co. Dublin, next to the Martello tower that features in the opening section of Ulysses by James Joyce (qv). The nautical imagery characteristic of the early international style is particularly apt in the location, and the three cascading curved bays, which form one end of the shallow V-plan, complement the contours of the neighbouring tower, pier, and fortified battery. Scott combined modernist design and traditional imagery in the Irish pavilion at the 1939 world's fair in New York, the first time that the independent Irish state was represented at an international trade fair. In fulfilling his brief to project both a distinct national identity and a modern, progressive image for the country, he took inspiration from the theme of the fair, 'a new world of tomorrow', and considered that airplane travel would allow buildings of the future to be viewed not only in elevation, but also in plan. Accordingly, he designed a modernist elevation – curved glazed walls with white concrete end wall – and a shamrock-shaped plan. Highly popular with the visiting public, the 'shamrock building' was selected by an international jury as best pavilion at the fair. Scott was conferred with honorary citizenship of the city of New York, and awarded a silver medal for distinguished services.

Now practising independently, during the Emergency, as economic exigencies severely restricted building activity, Scott executed several small-scale projects, including the Charlemont St. flats (ffrench-Mullen House) (1944), O'Rourke's bakery, Parnell St. (1943), and refurbishment for the bakers' trade union of Four Provinces House, Harcourt St. (1942–8). In the latter two he engaged with the trend in British design away from the cold, hard, unadorned look of early modernism, incorporating decorative finishes in a range of materials. He travelled with the Irish Red Cross to post-war Europe to advise on the design of wooden hospitals in St Lo, France, and Warsaw (1946).

CIÉ commissions: Busáras Appointed consultant architect to Coras Iompair Éireann (CIÉ) (1945), the newly formed semi-state transport company, Scott exercised final design approval over all projects for the company. His own firm fulfilled three choice CIÉ commissions, all in Dublin. First to be completed was the chassis factory, Inchicore (1946–8), a design that combined concrete vaults and structure steelwork, with large expanses of vertical patent glazing, and allowed for flexibility and extendibility as needs changed. A more radical design was the bus garage, Donnybrook (1946–51), the first of many collaborations between Scott and Danish engineer Ove Arup (1895–1988). The thin, concrete-shell roof is supported by vertical beams carried on perimeter columns (the side walls themselves carry none of the weight), thus allowing a spacious interior uninterrupted by internal walls or supports; natural light is admitted through glazed skylights extending end-to-end along the apices of ten barrel-vaulted bays. The first concrete-shell building in the world to be supported and illuminated in this manner, the project represented a ground-breaking application of Arup's ideas linking the technology of concrete-shell construction with principles of design.

Scott's foremost CIÉ project, and the most important of his career, was Busáras / Áras Mhic Dhiarmada, Store Street (1946–53). Conceived as a combined central bus terminal for long-distance services and offices for CIÉ staff, the project aroused lengthy controversy over its function, cost, scale, and proximity to the eighteenth-century Custom House of James Gandon (qv). On completion of the structure's reinforced concrete shell in 1949, work was suspended for two years as the inter-party government dithered over its use. In 1951 the new Fianna Fáil government determined a compromise whereby the upper-storey office space was assigned to the Department of Social Welfare, while the ground floor served as the CIÉ bus terminal. The latter occupies a double-height, curved concourse that forms a protruding arc at the right angle of the L-shaped plan formed by two rectilinear office blocks. A prominent exterior feature is an undulating concrete canopy that cantilevers seven metres from the concourse to provide shelter for passengers boarding buses. The building is remarkable for its finished surfaces. While the office-block facades are sheets of bronze-framed, double-glazed, plate-glass windows, the end walls are clad in white Portland stone, and the first storey in red brick. Extensive exterior and interior surfaces are meticulously detailed in mosaic, faience, and various woods.

The first large modernist public building erected in Dublin city centre, Busáras was a defining influence in Irish architectural history, establishing international modernism as the country's dominant style. It attracted considerable contemporary interest and acclaim internationally; groups of architects visited from overseas to observe it under construction and on completion. Scott was awarded the triennial gold medal for architecture for the building by the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland (RIAI) (1953–5).

From the late 1940s, Scott's firm, with offices at 19 Merrion Square, dominated Irish architecture. Their numerous commissions for public and private clients included the new Abbey Theatre (1958–66), and other familiar buildings throughout Ireland. In 1959 Scott took into partnership his two chief assistants, Ronald Tallon and Robin Walker (qv), practising as Michael Scott and Partners. With Scott himself taking a less active role, under his partners' influence the firm's style assumed a rigorously Miesian character, evident in their design of many of the iconic, sometimes controversial, buildings of the 1960s' building boom. In 1972 the firm was renamed Scott Tallon Walker. Scott retired from practice in 1975.

Arts patron and administrator A prominent patron and promoter of all the arts, Scott had a major influence on the acceptance of modernist art within Ireland. Having purchased the Martello tower next to his home, he designed its refurbishment as a Joyce museum (1961–2). His attempt in later years to sell Joyce's death mask generated a fierce row, involving disagreement with the Joyce family over ownership of the artefact; Scott eventually withdrew the mask from sale by auction at Sotheby's. While recovering from a heart attack in 1963, he conceived the idea of staging a major international exhibition of contemporary art. He assembled and chaired an organising committee, secured financial backing and sponsorship, and chaired the selection jury of the first Rosc exhibition (1967), which comprised 150 works created by living artists within the preceding four years. The first event of its kind in Ireland, the exhibition generated wide interest and enthusiasm, and made a lasting impact on all aspects of the arts, influencing practising artists, teachers, administrators, critics, collectors, and the general public. Scott remained chairman up to and including the fourth Rosc (1980), and thereafter continued as a committee member. He had exhibitions of his own paintings and drawings at the Dawson gallery (1967, 1975).

A long-serving member of the Arts Council (1959–73, 1978–83), throughout his first tenure, Scott, along with the council chairman, the Jesuit priest Donal O'Sullivan (qv), dominated the body, agreeing all important decisions between themselves, and consequently exercising effective control over state policy toward the arts. Scott was sometime chairman of the Dublin theatre festival, and president of the Irish Film Society. He was a member of the cultural relations committee of the Department of External (latterly Foreign) Affairs (1948–72), of the stamp advisory committee, and of the committee of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (1947–72). On the death of his friend Hilton Edwards (qv), he inherited the latter's shareholding in the Gate Theatre, and became a trustee. Involved in conservation initiatives, he was associated with Mariga Guinness (qv) and others in the Irish Georgian Society in efforts to preserve the architectural fabric of Mountjoy Square (1969), and supported the campaign to preserve medieval remains endangered by construction of new civic offices on Wood Quay (1978–9) (notwithstanding his firm's having competed ten years earlier for the commission).

Scott was elected a member (1936) and a fellow (1948) of the RIAI. He was a long-time member and president (1937–8) of the Architectural Association of Ireland. An honorary member of the RHA, and a corporate member of the RIBA (1977), he was honorary fellow of the Royal Society of Ulster Architects (1968), the American Institute of Architects (1972), and the Institute of Structural Engineers (London) (1976). He was awarded an Hon.Dip.Arch. by the College of Technology, Bolton St., Dublin (1967), and honorary doctorates by the Royal College of Art, London (1969), TCD (1970), and QUB (1977). He received the royal gold medal of the RIBA for work executed by his practice, presented by Queen Elizabeth II (1975).

Assessment Acclaimed as the leading figure in the introduction of modernist architecture in Ireland, Scott was one among several young Irish architects who adopted the international style in the 1930s. Over time he was perceived as preeminent, owing to his flair for publicity, association with key conspicuous projects, and the lengthy prominence of his firm. Researchers have emphasised his heavy reliance on assistants for many of his designs, and the collaborative approach to a project favoured within his practice. He has been described as an architectural Diaghilev, not so much a creative artist as an impresario, who assembled and managed a team of talents, integrating their work into his grand vision, his greatest gift being the capacity to judge as good or bad the ideas of others. Regarding a building as a work of integrated art, he incorporated sculpture, painting, and applied decoration in his designs, and commissioned notable work from artists within these genres.

A small man, with handsome sharp-jawed features, striking bleached-blue eyes, and suave manners, Scott was a notable wit and raconteur, and an obsessive womaniser. He was a flamboyant personality, and moved in a vast circle encompassing the world of politics, business, society, and the arts. He married Patricia Nixon (d. 1976), a London-born TCD graduate; they had four sons and one daughter. He died 24 January 1989 in his home at Sandycove, and was buried in Tahilla churchyard, Co. Kerry.