Adomnán: the man behind the milestone law

12 November 2019To mark the publication of A history of Ireland in 100 words here is the biography of Adomnán, who makes an appearance in the entry for the word 'Cáin', tax laws, specifically the landmark Cáin Adomnáin (law of Adomnán) decreed in 697 to secure the protection of non-comabatants in war.

Adomnán

by Aidan Breen

Adomnán (c.624–704), son of Rónán, was 9th abbot of Iona (679–704), biographer of Colum Cille, and saint in the Irish tradition. According to the genealogies, he was son of Rónán son of Tinne, one of the Cenél Conaill branch of the Uí Néill, and a kinsman of Colum Cille, his father being five generations descended from Colum Cille's grandfather, Fergus son of Conall Gulban. His mother's name is given as Ronnat, one of the Cenél nÉnnae branch of the Northern Uí Néill, situated in what is now Raphoe, Co. Donegal.

Adomnán is first mentioned in the annals in the year 687 (AU) as having been on a mission to Aldfrith, king of Northumbria, to obtain release of prisoners taken in a raid on Brega (685) by his half-brother Ecgfrith, whom he then escorted back to Ireland. On that occasion, he presented Aldfrith, who was Irish on his mother's side, with a copy of his ‘De locis sanctis’. The work was based on a narrative given to him by Arculf, a Gaulish bishop, supplemented by his own research in the library at Iona. It was mainly an account of travels in the Holy Land with descriptions of the holy places of Christendom. It shows a considerable knowledge of the works of Jerome and other patristic authors and makes reference to his consultation of libri graecitatis (‘books of Greek words’, probably a Greek onomasticon). It subsequently formed the basis for a later work by Bede on the holy places.

According to Bede's ‘Historia ecclesiastica’, it was while he was in Northumbria that Adomnán adopted the ‘universal observance’ of the church on the matter of the Easter dating, having spent some time with Ceolfrith and the Anglian monks at Wearmouth or Jarrow and having accepted their guidance on the matter. However that may be, he continued as abbot of Iona (which did not accede to the Roman Easter till 716) up to his death on 23 September 704. In truth, Adomnán's stand on the Easter question is not known, but it is likely that he was anxious to effect a reconciliation of Iona with the English and the majority of the Irish churches, which did not finally come till 716.

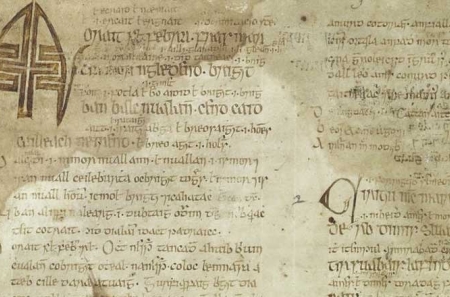

In 697 Adomnán journeyed again to Ireland where, at a synod in Birr (Co. Offaly), he promulgated the Law of Adomnán (Cáin Adomnáin), legislation intended to protect non-combatants in time of war by means of a system of fines. The accompanying list of guarantors naming ninety-one Irish ecclesiastical and secular potentates (including three from Scotland), is a genuine contemporary document. The law places particular proscription on the enforced use of women in war or raids, and imposes heavy fines – payable in part to the Columban community and in part to the kin or lord of the injured or deceased party – on those guilty of that offence and on those guilty of the murder, injury, or molestation of women. It is a humane and innovatory piece of legislation, which reflects Adomnán's concerns with the preservation of peace and civil order and the protection of women. The Law of Adomnán is a milestone in the development of Irish law.

Adomnán's major work, his ‘Vita Columbae’, written c.700, was based on both written and oral tradition, some of it derived from written memoranda of Cumméne Find, abbot of Iona 657–69, some other written notes (paginae), and partly from contemporary recollections. It displays a wide-ranging knowledge of the Bible and of hagiographical and patristic texts. It is a remarkable account, written in an eloquent Latin style, of the sanctity, prophecies and virtutes of a great Celtic saint, whom Adomnán venerated. Adomnán's intention of elevating Colum Cille to the status of a universal saint produced one of the earliest and finest hagiographical works to emerge from the Irish church.

The few penitential canons ascribed to Adomnán are quite probably his. The text is certainly of eighth-century date at the latest, the earliest manuscript (Orleans 221) being dateable to c.800. There is an explicit reference in canon 16 to one of the canons (c. 26) of the so-called second synod of St Patrick, which deals with the problematic matter of remarriage after divorce. This, and the following three canons (17–19) concerning the eating of carrion, which no longer exist in any other collection, are stated by him to have come from a collection of quaestiones Romanorum, a canonical compilation of the Romani. His awareness of the Romani provenance of the second synod makes it very probable that the ‘Canones Adamnani’ are of seventh-century composition. The differences in style between these canons and the other works of Adomnán do not prevent their having a common author: the convoluted syntax is typical of Adomnán's style and the ‘pedestrian’ prose is quite in keeping with the conventions of canonical Latin.

Adomnán's career was a remarkable achievement. He was singularly successful as a churchman, scholar, diplomat, and legislator, and his striving towards the unification of the Irish church may have promoted that second flowering of scholarly and literary activity that so characterises the eighth century in Ireland.

Sources:

AU; Cáin Adamnáin; D. Meehan (ed.), De locis sanctis (1958); Bibliotheca Sanctorum 1 (1961), 199–201 (C. McGrath); L. Bieler, Adomnani De locis sanctis CCSL 175 (1965), 183–234; idem, The Irish penitentials (1975), 9, 21–6, 176–81 (‘Canones Adomnani’); J.-M. Picard, ‘The purpose of Adomnan's Vita Columbae’, Peritia, i (1982), 160–77; M. Ní Dhonnchadha, ‘The guarantor list of Cáin Adomnáin, 697’, Peritia, i (1982), 178–215; H. Moisl, ‘The Bernician royal dynasty and the Irish in the seventh century’, Peritia, ii (1983), 120–24; Ó Riain, Corpus geneal. SS Hib. (1985), §§340, 714, 722.21, 733; M. Herbert and P. Ó Riain (ed.), Betha Adamnáin: the Irish Life of Adamnán (1988); M. Herbert, Iona, Kells and Derry (1988); A. O. Anderson and M. O. Anderson (ed.), Adomnan's Life of Columba (2nd ed., 1991); M. Ní Dhonnchadha, ‘The Lex Innocentium: Adomnan's law for women, clerics and youths, 697 A.D.’, M. O'Dowd and S. Wichert (ed.), Chattel, servant or citizen (1994), 58–69; T. O'Loughlin, Adomnán at Birr, AD 697: essays in commemoration of the law of the innocents (2001); A. Breen, ‘Adomnán mac Rónáin’, S. Duffy (ed.), Medieval Ireland: an encyclopedia (2005), 3–4; ODNB