Margaret Stokes: antiquarian scholar with an artist’s eye

20 September 2018We continue our Blog post series on the five Honorary Members featured in our exhibition 'Prodigies of learning: Academy women in the nineteenth century'. This month we look at Margaret Stokes

A talented artist and antiquary, born in Dublin, Margaret McNair Stokes lived in the city most of her life. The family had a large Georgian house at 5 Merrion Square, and Margaret was educated at home. She studied art and antiquities under the influence of her father, William Stokes, MD, MRIA (1804-78), and his friends. She maintained close contact throughout her life with her older brother, Whitley Stokes, MRIA (1830-1909), a Celtic scholar and legal administrator.

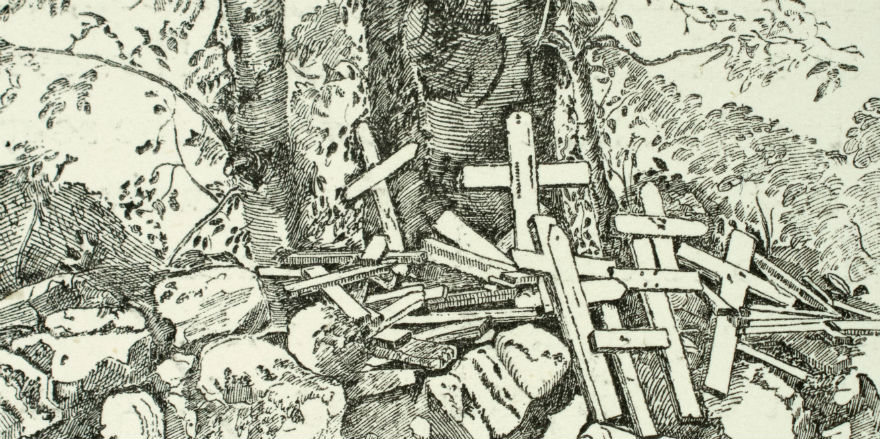

The family had a longstanding association with the Royal Irish Academy, and the scholarly circle in which Margaret worked in her early career included George Petrie, MRIA, Samuel Ferguson, MRIA, J. H. Todd, MRIA, and Edwin Wyndham Quin, earl of Dunraven, MRIA. She edited and illustrated some of their publications on Irish antiquities, architecture and manuscript heritage. Among her best known artistic achievements are the illustrations she provided for Samuel Ferguson’s The Cromlech on Howth: a poem (London, 1861). The book includes her intricate reworking of images from the Book of Kells, along with watercolours depicting scenes from Howth and Clontarf on the north Dublin coast.

Margaret Stokes’ artistic talent emerged clearly in her illustrations for Samuel Ferguson’s Cromlech of Howth (London, 1861).

The Cromlech on Howth: a poem / by Samuel Ferguson (London, 1861), plate 4.

By the time she came to publish her research under her own name, Margaret was an informed and experienced editor, photographer, and illustrator. Two books based on her research, Early Christian architecture in Ireland (1878) and Early Christian art in Ireland (1887), include many of her accomplished drawings. Her Early Christian art was regularly reprinted well into the twentieth century and helped mould artistic perceptions of Irish heritage in the newly independent Ireland.

Her High crosses of Castledermot and Durrow (1898) combines photography and original artwork in her pursuit of visual accuracy. Margaret Stokes had a very clear view of how her illustrations of high crosses were to be presented, using her technique of photography and art combined. Then, as now, producing high-quality images of such monuments in the landscape required skill and patience. In her communications with the RIA publications committee, she insisted that the illustrations of medieval high crosses she had personally prepared were integral to her work and could not be replaced by alternative photographs of the same objects.

‘Everyone who has experience of photography in the case of half obliterated bas-reliefs or inscriptions, will support me in saying that the result depends on the season, the day, the hour and the aspect of the skies. … my paintings are worked on a certain foundation – that foundation being a platinotype print from a certain negative. The faintest indications of design discoverable in this negative are brought out by my brush. In a different negative the design may be wholly misrepresented – or obliterated if taken under a different aspect of sunlight. … the primary object of my work is not the same as the photographer’s. The method which I have found by experience to be the best to follow for my purpose is to make rubbings in the first instance so as to be sure of what the pattern or design really is which may look so different or so incomprehensible either to the naked eye or in a photograph taken under ordinary conditions of light. But, having once secured, through means of the rubbing, the true nature of the design, then to watch for the moment when the sun illumines the sculpture so that the edges of the half-effaced outline revealed first in the rubbing, come out in agreement with it.’ (RIA, MS 12 L 36)

Castledermot South Cross (west face) from High crosses of Castledermot and Durrow (1898)

In 1876, Margaret Stokes became the first woman born in Ireland to be elected an Honorary Member of the Royal Irish Academy, and she included reference to this on the title page of her later books. (Her father, William, and both her brothers, Whitley and William, were already full members, but women were not eligible for full Academy membership.)

Constantly interested in new experiences, she wrote two books drawing on her continental travels late in her life: Six months on the Apennines (1892), and Three months in the forests of France (1895). In pursuing research on European architecture and sculpture at the sites of early Irish monasteries, she explained that she was attempting ‘to discover the reason for the development of certain styles in Ireland’. Rather than tracing the stories of medieval Irish monks, she was interested in the art and architecture they would have seen, believing them to have been important channels of influence between Ireland and Europe. Her interest in such associations extended to the folk customs of her own day, as in her visual analogies of funeral customs in both countries.

Three Months in the Forests of France, fig. 50 Funeral custom, Cong

She was also active in the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland and in the County Kildare Archaeological Society. Her Academy obituary (Royal Irish Academy, Minutes of proceedings, 1901) noted ‘it will be hard to find again the same passionate devotion to the object of her study, and the same artistic excellence in the elaboration of her work’.

Bernadette Cunningham

Deputy Librarian

Main image: Margaret Stokes sketching the High Cross of Moone, Co. Kildare, photographed by Lord Walter Fitzgerald in July 1897. (Journal of the Co. Kildare Archaeological Society, Vol. 3, 1899-1902, p. 200)

Listen back to the Lunchtime Lecture by Dr Marie Bourke 'Margaret Stokes (1832-1900): Antiquarian, Artist, Writer – Pioneer

Further reading:

Lord Walter Fitzgerald, ‘In memoriam. Margaret Stokes’, Journal of the County Kildare Archaeological Society, 3 (1899-1902), 201–5

Janette Stokes, ‘Margaret McNair Stokes’, Irish Arts Review, 9 (1993), 217–19

Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh, ‘Authorship denied: Margaret Stokes, Rev. James Graves and the publication of Petrie’s Christian Inscriptions’, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 138 (2008), 136–46

Andrew O’Brien and Linde Lunney, ‘Stokes, Margaret McNair’, in Dictionary of Irish Biography (2009) (dib.cambridge.org)

Elizabeth Boyle, ‘Margaret Stokes (1832-1900) and the study of medieval Irish art in the nineteenth century’, in Ciara Breathnach, and Catherine Lawless (eds), Visual, material and print culture in nineteenth-century Ireland (Dublin: Four Courts, 2010), 73-84.

Philip McEvansoneya, ‘More light on Margaret Stokes and the publication of George Petrie’s Christian Inscriptions in the Irish Language’, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 141 (2011), 149–66

Peter Murray, ‘Margaret Stokes, Celtic connoisseur’, Irish Arts Review, 35:3 (2018), 126–9