Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks: Tinkers Encampment: Blood of Abel, Jack B. Yeats

02 May 2015Tinkers Encampment: Blood of Abel, by Jack B Yeats, 1940

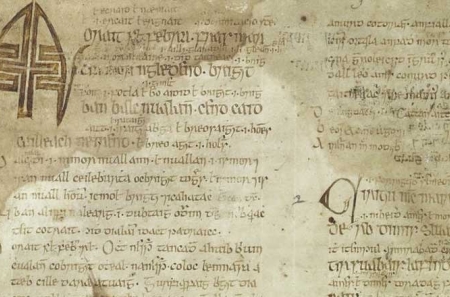

Jack B Yeats completed this painting in 1940. It went on show in the RHA in 1941. Not a work of realism, it subscribed more to his expressive and modernist approach which he had adopted since the 1920s.

The painting was sculpted out of paint and is thought to represent a strange blend of past and present, real and imaginary ‘that symbolise, as the poet Thomas MacGreevy suggested, humanity at its most benevolent but also at its most disposed and transient’.

Yeats had though deeply about the imagery, he told the buyer of the work in 1942 that ‘although this picture did not take long to paint, it was taking shape in my mind for over two years’.

Learn more about the Art and Architecture of Ireland project.

Catch up on all of the Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks features.

Read the Irish Times Article in full.

Jack B Yeats also features in our Dictionary of Irish Biography project, read his entry below.

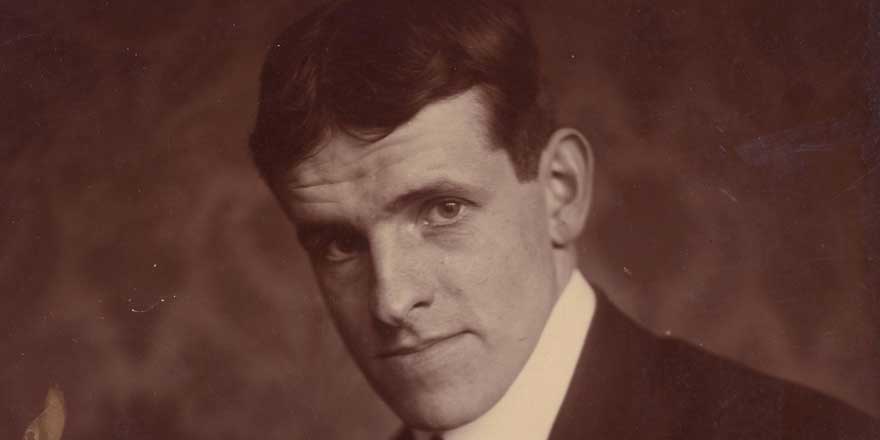

Yeats, Jack Butler

by Bruce Arnold

Yeats, Jack Butler (1871–1957), painter, was born 29 August 1871 at 23 Fitzroy Road, near Regent's Park, London, youngest of the four surviving children of John Butler Yeats (qv) and brother of William Butler Yeats (qv),Elizabeth Corbet (‘Lollie’) Yeats (qv), and Susan Mary (‘Lily’) Yeats (qv). In his early years he was known as ‘Johnnie’, and, unlike his father and brother, never used the ‘Butler’ name, only the initial. His mother was Susan Pollexfen. The Pollexfens were a nineteenth-century merchant family established in Sligo in the milling and shipping business. The Yeatses were impoverished gentlefolk with landholdings in Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny. This was lost through John Butler Yeats's bad management. They were settled in Dublin in the mid nineteenth century.

Upbringing: Sligo and London Jack spent his early years living in London and then in Sligo. His father had been a barrister in Dublin but became an artist in London and moved the family there after the birth of the eldest child, William Butler Yeats. He was financially unsuccessful as a painter, and the family faced much privation, residing in various lodgings. As a result his wife spent lengthy periods of time with her parents in Sligo. Jack Yeats's early experiences were of travel. His love of the sea was to inspire many paintings, and developed during sea voyages in his grandfather's ships from Liverpool round the northern coast of Ireland to Sligo.

By the age of nine Jack had settled in Sligo in the care of his grandparents, an arrangement that was to last until he went to art school six years later, in 1886. He claimed Sligo as a formative influence in his life, and said he rarely painted a picture ‘without a bit of Sligo in it’. He worked hard at school, was competitive and successful in most subjects, and showed an early facility in drawing and particularly in caricature. He was a happy child, in marked contrast with his brother, who was moody and introspective, and rather frightened of his grandfather.

Jack, on the contrary, was particularly fond of William Pollexfen, and exercised a youthful authority over this powerful and forbidding man of the sea. In his youth Pollexfen had commanded a coaster called the Dasher, and he told Jack Yeats stories about the sea and pirates which inspired his early drawings, his plays for children, and his later paintings, many of which show an outstanding grasp of seafaring life. Within his vast output of paintings, watercolours, and drawings, a very substantial number draw their inspiration and subject matter directly from the Sligo life in which he spent his early years. The powerful, bearded figure of a seafaring man often figures in his work.

Unlike his brother and sisters he was surrounded by comfort and security. He lived in a large house with servants and grooms, and travelled about with his grandfather. He returned to London to enrol at art school, first to the South Kensington School under Professor Frederick Brown in 1887. He then went to the Chiswick School of Art in Bedford Park, to which suburb the family had moved. He recorded being at the West London School of Art from 1890 to 1893, and also at the Westminster School of Art from 1890 to 1894, making something of an itinerant art student out of his life at the time, though he saw nothing strange in it.

He found quite uncongenial the straitened circumstances at home. These included the burden of having to contribute to the family income. He escaped into the world of his own art. He also escaped into the entertainment world of the Buffalo Bill Cody shows at Earls Court, near to one of the houses in which the family lodged. He drew obsessively cowboy subjects. While an art student he witnessed the efforts of his brother and his two sisters to earn money to keep the family together, and by 1888 he was himself contributing drawings to publications such as The Vegetarian. He was also privately commissioned to design menus and ‘doyleys’, and he began selling drawings directly through a shop in Piccadilly. He was influenced in his early work by Randolph Caldecott and Phil May. He also greatly admired the art of Thomas Hood.

He led an independent existence at Bedford Park. He had a great sense of fun, got on well with everyone, with the possible exception of his father, and remained the least troubled of the children. Towards his father Jack displayed a reserve due to the blame he placed on his father's head for the failing health of his mother.

Marriage and early career in art; Ireland In the early 1890s Jack Yeats determined on marriage. He had met Mary Cottenham (‘Cottie’) White in 1889. She was a fellow student at Chiswick, and came from a well-to-do family with Isle of Man connections. In 1891 he announced his intentions to his father, and was released from financial obligations to the family since he was now saving for his own and Cottie's future. He was already surprisingly successful as a freelance illustrator, comic artist, and sporting artist recording athletics and racing scenes around the country. In these years, when all members of the family contributed to the expenses of running the home, Jack's contribution tended to outstrip that of other siblings.

Jack and Cottie were married (August 1894) in Gunnersbury and went on honeymoon to Dawlish, Devonshire. They moved into a house in Chertsey, Surrey, and he continued to find employment in both freelance and regular commissioned work as an illustrator. Cottie herself was an accomplished watercolourist. Though they lived frugally, they enjoyed an additional income through a family settlement made on Cottie during her lifetime. They decided to move to the west of England. The Pollexfens had come originally from Devon and Jack discovered a cottage in Strete, four miles south of Dartmouth. More land was acquired, and an old barn was repaired as a studio overlooking the Gara river. It took almost two years to complete the move.

Yeats prepared in their new home for his first exhibition at the Clifford Galleries. This took place late in 1897. Much of the work consisted of drawings and watercolours of life in the west of England. Scenes of racing, boxing, fairgrounds, cider-making, children, and animals made up a substantial number of works, and the critical success was remarkable. P. G. Konody wrote: ‘But quite apart from the exquisite humour of these sketches, there is another reason which makes them quite remarkable and worthy of attention. They show an astounding capacity for grasping and retaining the impression of certain short moments’ (quoted in Arnold, 68). Thirty-nine individual publications noted the show, many of them praising it warmly. Over a quarter of the works shown were sold, and the artist's talent was noticed by the playwright and patron of Irish artists, Augusta, Lady Gregory (qv). She wanted Jack, like his brother, to become involved in the artistic revival of the late nineteenth century. But he had no intention of returning to Ireland. His wife did not favour the idea, and he was reticent about a literary movement that was becoming very much dominated by his elder brother.

Yeats did return to Ireland as an artist, however, and travelled in the west of the country, painting in watercolours and filling sketchbooks with anecdotal drawings of people and places. He loved the odd and the unusual. Fights, disputes, parades, circus giants and dwarfs, above all the scenes at race meetings and fairs, repeatedly captured his imagination and provided him not only with subject matter for paintings but with illustrations he was able to sell.

Yeats held his first exhibition in Dublin in 1899, and again it was widely mentioned and in very positive terms. The writer and painter George Russell (qv) wrote in the Dublin Daily Express: ‘These sketches of the west of Ireland reveal a quite extraordinary ability in depicting character and movement’ (quoted in Arnold, 85). Yeats used a form of title that referred to ‘Life in the west of Ireland’ both for this and for later shows, and he kept this description also for his publication of illustrations (1912), called Life in the west of Ireland.

In 1900 his mother died, worn out and both physically and mentally impaired by the difficult life imposed on her by her husband's ineffectual and self-indulgent behaviour. Jack Yeats was greatly upset by the death. He arranged the plaque in St John's church in Sligo, pointedly leaving out the name of his father from those listed as having placed it in the nave.

From the end of the nineteenth century until 1910, when Jack and Cottie moved to Ireland and settled in Greystones, Co. Wicklow, he and his wife regularly visited the country and spent time in the west. They stayed with Lady Gregory at Coole Park. They revisited Sligo, explored Donegal, went to Kerry, and became marginally involved in the Irish literary revival in Dublin.

John Masefield, the later poet laureate, was a close friend. Together, the two men had played games along the Gara river, Jack constructing cardboard boats, Masefield furnishing them with equipment and even at times little engines. They bombarded and sank their own creations, Masefield writing vigorous lyrics about each vessel, Yeats producing drawings. In 1905, through his contacts with the editor of the Manchester Guardian, Masefield obtained for Jack Yeats and John Millington Synge (qv) a commission to visit the congested districts in Galway, Connemara, and Mayo. Synge wrote about their experiences, Jack Yeats did illustrations. The friendship flourished. They were like-minded men, contemplative, independent, reticent. Synge sought Yeats's help with certain costume aspects of his play ‘The playboy of the western world’, and Yeats was able to suggest the appearance and clothing of the hero, drawn from his experience of race meetings on Bowmore Strand in Sligo when he was a boy.

The two Yeats sisters, ‘Lily’ and ‘Lollie’, together with their father, who came at a later date, moved to Dublin. There they set up the Cuala Press and the Dun Emer Guild, and became engaged in fine printing, embroidery work, and other cottage industry activities. Somewhat reluctantly both William Butler Yeats and Jack Yeats were drawn into their sisters’ ventures, and Jack produced broadsheets which were coloured by hand. In 1908 John Butler Yeats left Dublin for New York. As with most of the movements in his life, it was meant to be a temporary shift of territory. But he never returned.

Jack Yeats was not a great traveller, but he did go to New York in 1904. He had a liking for American stories of adventure. He met Mark Twain, whom he greatly admired, and also the lawyer John Quinn (qv), who bought early Yeats watercolours and drawings.

Artistic development: oils; a changing Ireland So far his career as a painter had taken a rather limited course. His abilities as a watercolourist were not matched when he turned to oil painting, for which he had studied inadequately, in part as a result of the Yeats family's financial needs while he was at art school. It told in these early years. His canvases in the first fifteen years of the twentieth century lack any convincing colour sense. When engaged in the representation of human figures, as he was with the series of oil paintings used as illustrations to Irishmen all (1913) by George Birmingham (qv), he achieved strength of design, a clear line, and good chiaroscuro. But he was still drawing in paint, and it worked less well when he produced landscapes. Early examples are often unsubtle and rather flat.

In 1913 Jack Yeats was chosen for the Armory Show in New York, and sent to it one of his great early paintings, ‘The circus dwarf’ (private collection). He had already shown the work in London (1912), to some critical acclaim. The art critic for the Star newspaper, A. J. Findberg, in an article about Yeats, wrote: ‘The people Mr Yeats is interested in are a rough, hard-bitten, unshaven, and generally disreputable lot of men. His broken-down actors practising fencing, his “Circus dwarf” . . . are subjects no other artist would have chosen to paint’ (Star, 16 July 1912). It is unlikely that other painters would have painted the political subjects that attracted Yeats, but politics were very much part of Irish life, and he was increasingly identifying his work at this time with the events heralding the Easter rising. Gun running was one of these, a by-product of it his poignant study of pity, ‘Bachelor's Walk: in memory’ (location unknown). This painting showed a flower-girl placing flowers on the spot in the street where a person was shot down by British soldiers who had unsuccessfully tried to prevent the Howth landing of arms. Later political works included ‘Communicating with prisoners’ and ‘The funeral of Harry Boland’ (Model + Niland Gallery, Sligo).

His work did not sell. From a professional point of view his and Cottie's decision to settle in Ireland had not been a success. In 1915 Jack Yeats had a nervous breakdown. It lasted into 1917. He had been made an associate of the RHA in 1914, and a full academician the following year. He was recognised for the originality of his vision, for his increasingly central role as the painter of Irish life at a time when nationalism demanded icon-makers. And his recovery was helped by this growing sense of a role in Dublin and in Irish society.

He painted views of the city, of its characters, of its sporting events. The country was going through the turmoil of the war of independence, the treaty, the civil war, and the grim political antagonisms that characterised the early 1920s. During this time Jack Yeats produced a growing number of large and increasingly confident works. They show us crowds attending sporting events at Croke Park, women singing in the street, in bars, or in trains, theatrical subjects, men of the streets including newspaper sellers and pavement artists. His early concept for exhibitions, which he entitled ‘Life in the west of Ireland’, had been broadened into a succession of works that depicted the life of his country.

Yeats was 50 years old when Ireland became independent. Never directly involved in politics himself, he was nevertheless deeply affected by the civil war, and, as a result of meeting Éamon de Valera (qv) in Paris at the Irish Race Congress in 1922, became and remained sympathetic to the political views of him and his followers. In this his ways diverged from those of his brother, who had supported the treaty and had become a member of the senate. He gave at the congress the only lecture of his life, published as Modern aspects of Irish art (Dublin, 1922). He managed to do so without naming a single painter.

Development of a modern style He sided with modernism. In Dublin in the early 1920s this had a distinctive meaning. In the absence of a strong artistic tradition based on academic art, the arrival in the city of modernist principles, of abstraction, of a movement that related to European painting rather than to London, was successful. Jack Yeats sided with the artists who formed the Society of Dublin Painters, led by Paul Henry (qv), and became one of their number. He met Oskar Kokoschka and they became friends. He derided the dominance of Paris and London in artistic life generally. This had been a theme in his Paris lecture, and he expressed it in respect of Picasso, suggesting that he ‘would be more thrilling to his time and generation if he had jumped straight out of Spain without the use of Paris’. He said this in a letter to Thomas MacGreevy (qv) who was then his great champion, and who was another modernist, writer, and poet. MacGreevy crossed swords with Thomas Bodkin(qv), a more conventional art critic, over the direction Yeats was taking and the magnitude of his contribution to modern art and thought in the city. It led to a public controversy.

It was a time of much public debate on art. Dublin in the early 1920s was described as being like ‘the Athens of Pericles’, and it was a truthful insight into the ferment of thought and debate about the cultural life of the new state. Yeats was happy to be part of this, and his exhibitions – he showed work in New York, Rome, Pittsburgh, London, Liverpool throughout the decade – gave him the opportunity to expand on the role of representing more and more widely the chosen theme of Irish life.

During the 1920s Yeats became increasingly conscious of stylistic restrictions in his work. He was still having difficulties with colour and with the reconciliation of tone and compositional balance. He sought freedom, and it was not available to him in the more conventional techniques he was employing. He dealt with the matter summarily. He abandoned his old palette and chose a new one, using primary colours quite freely and applying paint in a rich and generous way. He substituted the palette knife and his fingers for the brush. He chose to work on large canvases, and within them to present quite often a close focus on the subject matter. Large horses’ heads, strong-faced Irish men and women, filled large picture areas. His characteristics were the use of ultramarine and cobalt blue in generous representation of shadow and of distant horizons. Cadmium yellow, used at times direct from the tube, and alizarin crimson used in the same way, produced works which unfailingly caught the attention and caused former critics of the lameness of earlier work to marvel at this extraordinary rejuvenation.

Writing; final years But although Dublin marvelled at the work, the resources to buy it were thinly spread in Irish society at the time, particularly those interested in modernism, and Yeats's work did not sell at all well. His output, substantial during the 1920s, fell off in the following decade, and in a mood of self-doubt he turned to writing. He produced a number of volumes – Sligo (London, 1931), The charmed life (London, 1938), The Amaranthers(London, 1936), and The careless flower (London, 1947) – and he had high hopes of becoming a successful writer. He had the same aspiration about plays that he wrote during the 1930s; his play ‘In sand’ was performed at the Peacock Theatre in 1949.

In 1941, through the intervention of John Betjeman, who suggested the idea to Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in London, he was invited to show there with William Nicholson. The exhibition, opened on New Year's day 1942, was a singular success, and the critical acclaim raised his stature greatly in Ireland. Later that year he was made an honorary member of the United Arts Club, Dublin. At the end of the second world war he was given a retrospective exhibition in Dublin, and became in his last years a revered artistic figure, receiving honoraryD.Litt. degrees from Dublin University (1946) and the NUI (1947). His output was vast. He painted more than 1,100 works in oil, over half of them in the last twenty years of his long life.

He died 28 March 1957; he had begun to spend periods in the Portobello Nursing Home in the 1940s, and had lived there permanently from 1955. The members of the government of the day, led by Éamon de Valera, and the main opposition parties, turned out at the funeral, and stood on the pavement outside as his coffin was brought from the church. He is buried in Mount Jerome cemetery. Portraits by Seán O'Sullivan (qv) and Estella Solomons(qv) are in the Model + Niland Gallery, Sligo; a portrait by J. S. Sleator (qv) is in the Crawford Municipal Art Gallery, Cork; and the NGI holds a portrait by Lilian Davidson (qv), a portrait by his father of Jack in childhood, and a self-portrait in pencil.

No Irish painter matched Yeats in public esteem at the end of his life, and his reputation has grown immeasurably since his death.