New DIB 'missing person': Pat Tierney

13 January 2020Street poet and activist, Pat Tierney, has recently been added to the DIB as a 'missing person'. In his writings Tierney candidly explored the trauma and abuse he experienced as a child in industrial schools.

Pat Tierney

by John Gibney

Patrick (Pat) Tierney (1957–96), author and activist, was born in Galway on 4 January 1957 to Bridget Tierney of An Cheathrú Rua (Carraroe), Co. Galway. The identity of his father was not recorded. His mother worked as a live-in domestic at St Mary's College, Galway, and while Pat lived with his grandparents for a period, at the age of eight months he was placed in St Anne's Orphanage in Galway. His family stayed in contact with him for the first three years of his life; this ceased after they moved to Longford, and subsequently to England in late 1961. He would have no further contact with them until his teens. In 1964 he was moved to the more brutal environment of St Joseph's Industrial School in Lower Salthill, and in 1967 was fostered out to a farming couple, Stephen and Delia King, in Castlegar, Co. Galway, where he also attended the local national school. It was here that Tierney's interest in poetry was aroused, with the story of Antaine Raiftearaí (qv) proving an enduring influence.

Tierney was assessed with learning difficulties and from 1969 attended the Brothers of Charity's Holy Family School in Renmore. His education progressed rapidly, but he was also sexually abused by one of the brothers. Tensions within the Kings' marriage saw his relationship with his foster mother deteriorate, and she requested that he be removed from the household. This permanently damaged his relationship with her, though he remained in touch with the couple for a period in later life. A sympathetic social worker arranged a job and accommodation in Galway, but Tierney became involved in petty crime and was eventually detained in St Laurence's Industrial School in Dublin. He returned to Galway after his release but was detained in St Patrick's Institution in Dublin for theft in 1973. While there, an aunt in Rochester, Eileen Carter, contacted him, having herself been contacted by Irish social services.

On his release Tierney resided at Priorswood House, Coolock, and joined Sinn Féin. He then travelled to England and established cordial relationships with his aunt and members of his extended family in Rochester; his birth mother, however, rejected any attempts at a meaningful relationship. While in England he became involved in petty crime once more and was deported in 1975 after being detained for assault and theft. Tierney rejoined Sinn Féin, partly as he felt that it offered a degree of camaraderie and focus that could curb his self-destructive tendencies. An enthusiastic activist in a turbulent era, he remained a lifelong republican.

In 1979 Tierney emigrated to the US, working illegally in Detroit before moving to Arizona, where he was involved in organising Arizona's first St Patrick's Day parade in Phoenix. He also began to perform public recitals of his own poems and those of other Irish writers, foreshadowing his later activities on the streets of Dublin. He spent a period working on fishing trawlers off Massachusetts before moving to Wyoming, working in oilfields and on ranches. Having begun to use recreational drugs in Detroit, he now began to take methamphetamine intravenously. His socialising intensified, as did his drug and alcohol consumption, after moving to San Francisco. Following an attempt at suicide Tierney entered a rehabilitation programme in Florida. He then travelled to Newfoundland, where the Irish heritage of the region made a deep impression and facilitated his writing. He honed his skills as a performer, making a living from performance as he did so. His sojourn in Newfoundland was 'the first time this bardic tradition – this idea of writing poetry and getting paid for it – came upon me' (Kearns, 230). He left Canada to avoid deportation, eventually returning to Ireland in June 1988.

In September 1988 Tierney moved into a flat in Eamonn Ceannt Tower in Ballymun; it would be his home for the remainder of his life. Tierney devoted himself to his writing with increasing conviction. Poetry had, as he put it, 'a way of putting me in touch with the humanity which had perhaps been suppressed in me since childhood' (Tierney, 198). He worked on building sites and began to recite verse at festivals and on the streets of Dublin, where he became a familiar figure on Grafton Street. Tierney self-published two volumes of poems. Sheets to the wind (1988) contained many of the ballads he had composed in Newfoundland, while My first wake (1990) also contained a short story and pointed to a definite progression in his writing. The volume evoked life in the west of Ireland and in Dublin, along with the trauma of his upbringing; it also contained a bilingual poem on Raiftearaí. Tierney's poems and ballads often revealed his republican beliefs and a strong sensitivity to nature, with W. B. Yeats (qv) an obvious influence. Tierney viewed the public performance of poetry as a tradition that he was seeking to revive, though was aware that street performing meant that he had to choose his poems carefully.

Small of stature (a fact he attributed to childhood malnutrition), Tierney was charismatic, energetic, intelligent and engaging, with a natural empathy for the marginalised and an aptitude for organisation. In 1989 he established the 'Ceannt Tower Rhymers Club' in Ballymun, teaching local children to write poems and rhymes, and edited a bilingual (Irish and English) anthology of their work, Spring song (1991). Having raised the funds to publish it from a variety of sources, he hoped to see such projects replicated nationwide.

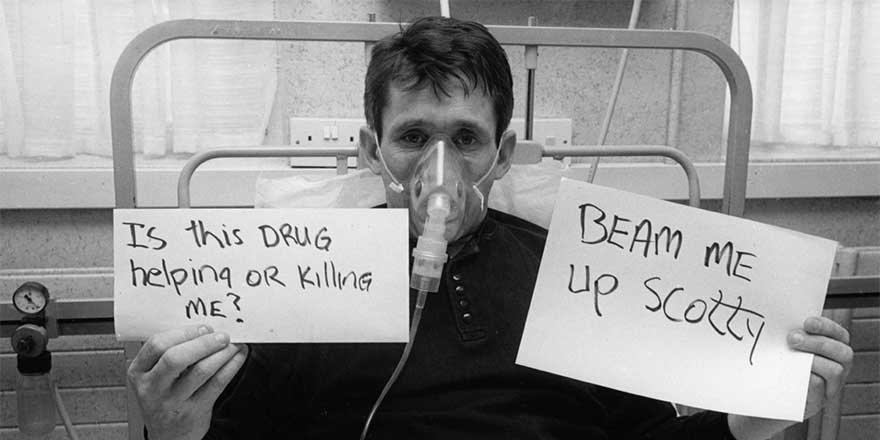

In 1991 Tierney was diagnosed as HIV positive, presumably due to sharing needles during his drug use in the US. The diagnosis dominated the closing sections of his most substantial work, the acclaimed memoir The moon on my back (1993). Published under his own imprint, it offered lucid and revealing accounts of Irish life in the 1960s and 1970s, and the Irish emigrant experience in the US in the 1980s. It also displayed an acute awareness of the psychological damage inflicted upon Tierney by Ireland's institutional system. While not a success at the time, a documentary adaptation was later filmed. Tierney decided to move away from youth work after revealing his HIV diagnosis in the memoir, and in late 1993 he was officially diagnosed with AIDS. He became a vocal campaigner for AIDS awareness, and better treatment for HIV and AIDS sufferers, a role that gave him a new sense of purpose.

Tierney's health worsened as the disease progressed. Having had a number of relationships, he felt that AIDS would preclude him from a family life and was deeply pessimistic about his future; an unsuccessful stage adaptation of his memoir had left him in financial difficulty. In December 1995 he made a final, unsuccessful, attempt to find out the identity of his father from his mother, who refused to speak to him. He became deeply depressed and, having hinted at suicide as an alternative to death from AIDS in the closing pages of his memoir, at the end of December 1995 Tierney began to tell friends and acquaintances that he intended to take his life on 4 January 1996; his thirty-ninth birthday. His body was found in the grounds of Corpus Christi Church on Griffith Avenue in Dublin on the morning of 5 January 1996; he had hanged himself. In the preceding days he had repaid debts and had spoken openly about his abuse at the hands of religious orders in Galway.

Tierney was cremated in Glasnevin Cemetery. In life he was held in high regard by a wide and diverse range of friends and acquaintances; those present at the non-religious funeral service that he planned himself ranged from the children of the Rhymers Club (who sang tributes to their founder), to then Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht, Michael D. Higgins. Some of Tierney's ashes were scattered at the top of Grafton Street, where he had continued to recite poetry; the remainder were scattered in the River Liffey. The respect in which Tierney was held in Ireland's literary community was reflected in tributes paid to him by the poets Theo Dorgan and Gabriel Rosenstock; the latter composed an Irish language ode to him.

Pat Tierney can perhaps be seen as a pioneering figure in terms of his activism, the nature of his public performances, and his willingness to openly discuss aspects of Irish life and experience that, in the early 1990s, were still largely unexplored, if not taboo. His 1993 memoir remains his most substantial literary monument.

Kevin C. Kearns, Dublin street life and lore: an oral history (1991), 227–231; Pat Tierney, The moon on my back (1993); 'The moon on his back' (interview with Pat Kenny, 13 Mar. 1993), www.rte.ie/archives/2018/0312/946851-pat-tierney-poet/ (accessed 21 Aug. 2019); Lorraine Freeney, 'Coming out from the cold', Hot Press, vol. xvii, no. xxiii (1 Dec. 1993), 12; Ir. Times, 10 Jan. 1996, 18 Jan. 1997; Theo Dorgan and Gabriel Rosenstock, 'Pat Tierney: In memorium', Poetry Ireland, 49 (Spring 1996), 3; John Kelly, 'The moon on his back', onedgestreet.com/the-moon-on-his-back/ (accessed 23 Aug. 2019)

A new entry, added to the DIB online, December 2019

Image courtesy of, and ©, John Kelly. Kelly's work can be viewed at OneEdgeStreet,

The Dictionary now comprises over 10,600 lives.

Follow the DIB on Twitter @DIB_RIA – where we post topical biographies.

All biographies are available at: dib.cambridge.org

© 2019 Royal Irish Academy. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Learn more about DIB copyright and permissions.