Gaelic Medical Manuscripts from the Academy Collections

We hope that you will enjoy exploring this exhibition which aims to highlight a lesser known aspect of medieval Irish society and the range of medical learning to which Irish doctors had access and which they made their own.

In medieval Ireland, the practice of medicine, like law and history was hereditary ― the work was confined to certain professional medical families through the generations. These professionals organised and regulated the medical schools in Ireland, notably the school at Aghmacart, Co. Laois, run by the Ó Conchubhair in the Mac Giolla Phádraig lordship of Upper Ossory. The work of two of the best known Ó Conchubhair doctors, Risteard Ó Conchubhair, 1561-1625, and Donnchadh Óg Ó Conchubhair, fl. 1581-1625, features in this exhibition. At Aghmacart, students were trained in medicine and in the compilation and translation of medical texts from the Latin.

Almost 100 medieval manuscripts survive that contain medical texts in Irish. The largest collection of these manuscripts is in the Royal Irish Academy. They consist mainly of translations or adaptations of continental Latin treatises into early modern Irish. The Irish practitioners were unusual in translating the texts into the vernacular rather than working from the Latin as was the norm elsewhere in Europe. Many of these Latin versions had been translated from Greek or Arabic by early practitioners in France and Italy. The compilations were made for practical purposes – for the use of doctors in the course of their working lives. The compilations shown here often consist of texts based on a variety of sources. The Lilium medicinae by Bernard of Gordon was one of the most popular texts used by the Irish doctors, but they used a very broad range of texts compiled by doctors at the medical schools of Montpelier and Salerno and other English and continental universities from the twelfth to the seventeenth century.

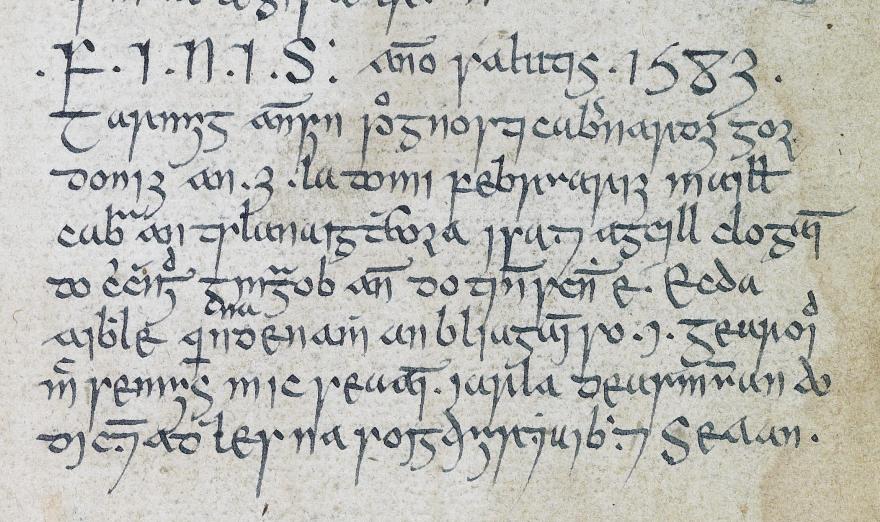

Medical learning in Europe had Graeco-Arabic roots. The bulk of the treatises shown here conform to the standard Arabic arrangement of diseases of the body ─ a capite usque ad pedes (‘from head to toe’). The texts deal with anatomy, diagnosis and prognosis, diet and regimen, gynaecology, obstetrics and pharmacology, as well as common illnesses and injuries. Occasionally the Irish doctors refer to patients whom they have treated or to events that have taken place in the neighbourhood as for example a note by the Leinster-based doctor, Corc Ó Cadhla, fl. 1577-84, who noted in RIA MS 24 P 15, in 1583, on completing his transcription of Bernard of Gordon’s Prognostica:

Ecda aibhle ar ndenamh an bliagain so .i. Gearoid mac Semuis mic Seaain iarla Deasmuman do dicennadh lesna sighdiuireadhaibh …

Great slaughters have been made this year, i.e. Gearóid son of Séamus, son of Seán, the Earl of Desmond, was beheaded by the soldiers …

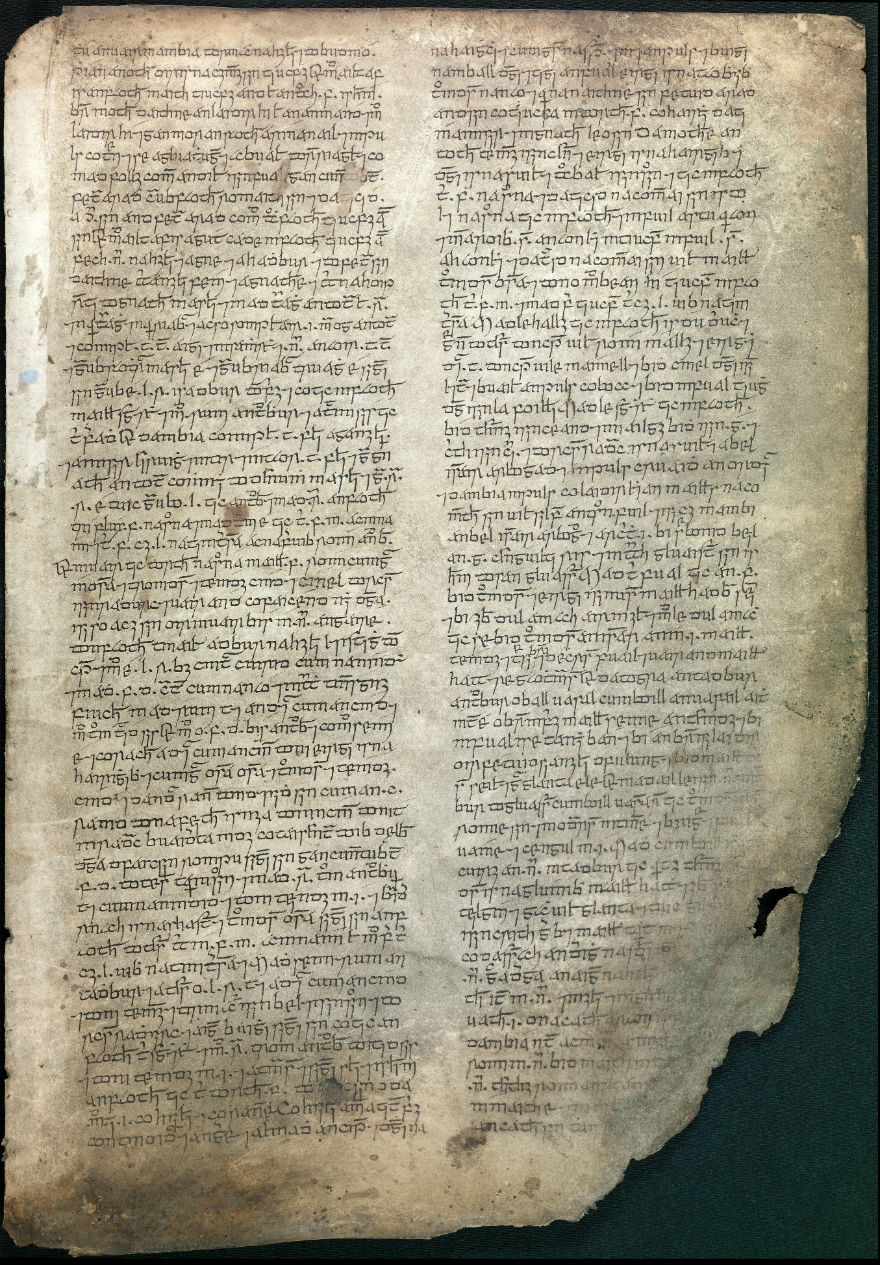

RIA MS 24 P 15, p.193, 15th and 16th centuries

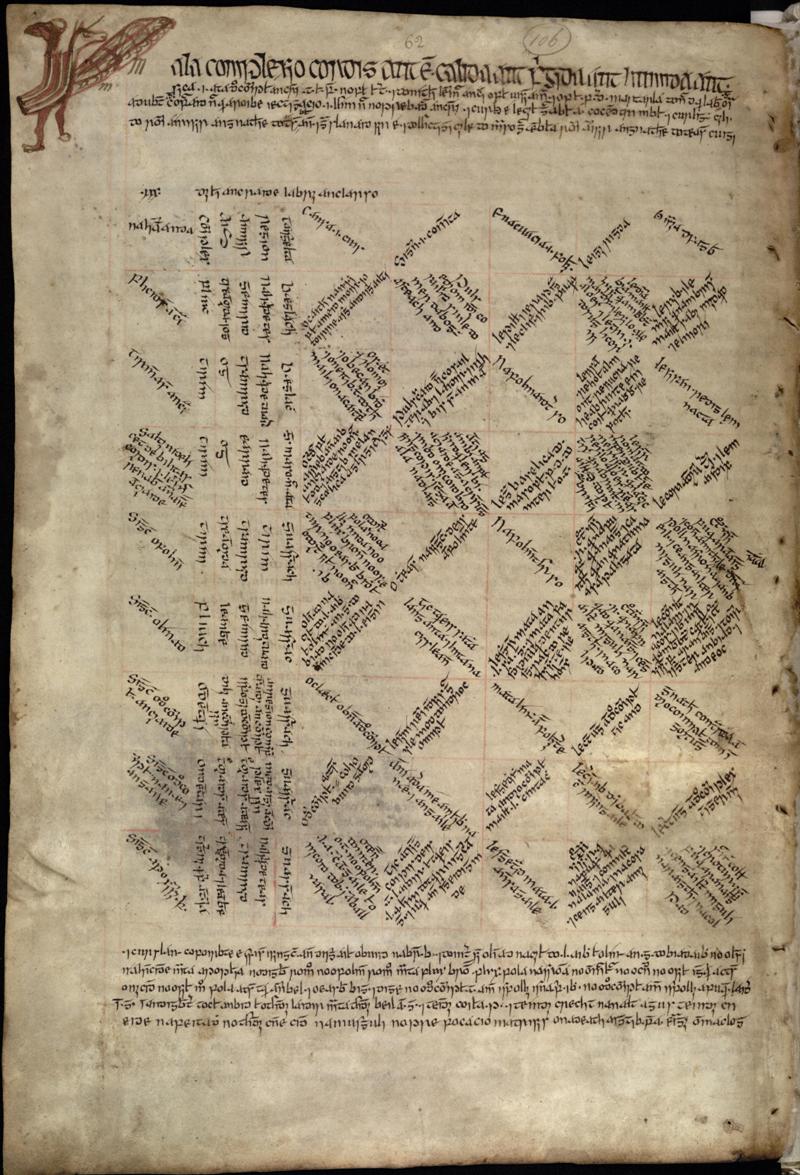

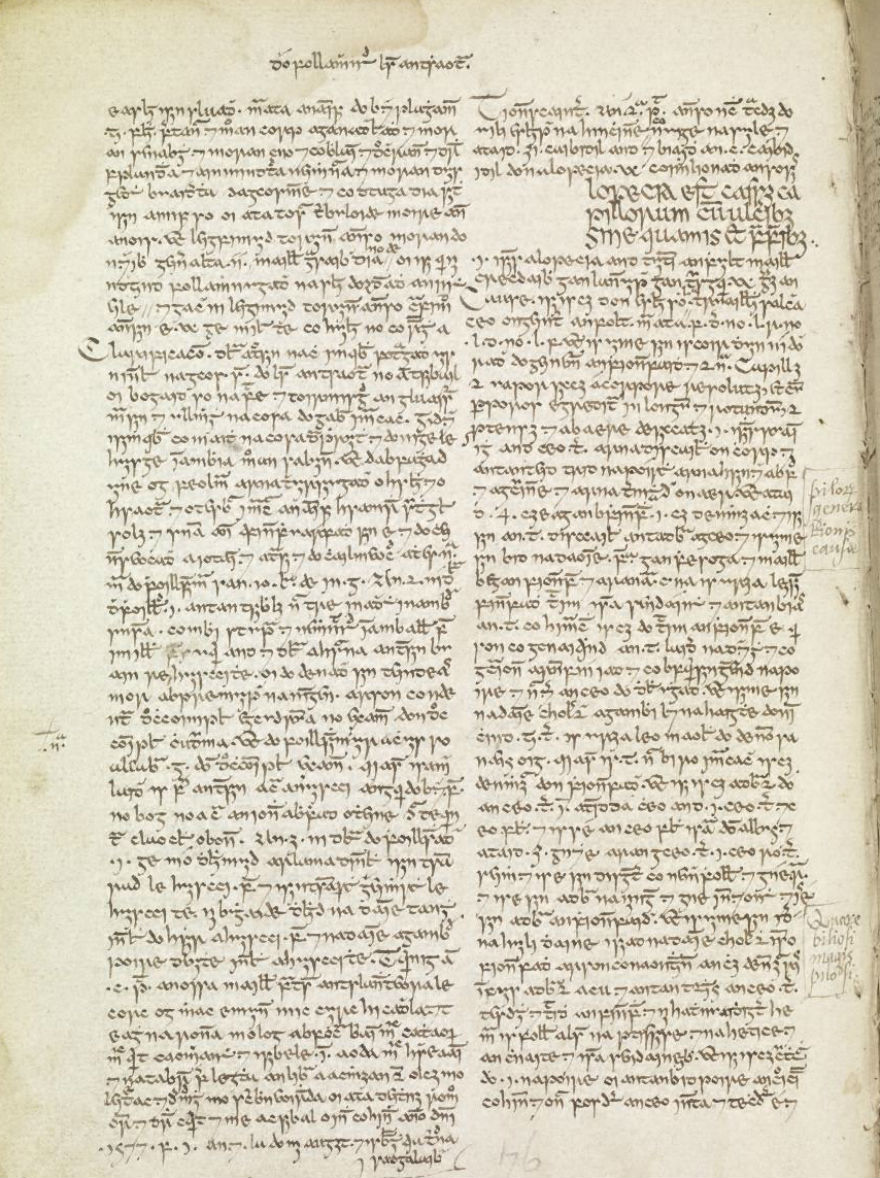

RIA MS 23 P 10 (ii), The Book of O'Lees, p.62, 15th century

The Book of O'Lees (RIA MS 23 P 10 (ii)), written in Irish with some Latin, contains a translation from Latin into Irish of a highly organised medical treatise, with 44 tables outlining details of diseases, each divided into 99 compartments, across, aslant, and vertical. These are coloured red and black, and comprise descriptions of different diseases, showing name, prognosis, stage, symptoms, cures, etc., of the disease in question. There are rough decorative drawings at the top left margin of many pages. A. Nic Dhonnchadha has shown that the text is a faithful rendering from the Latin Tacuini aegritudinum, which was itself translated from the Arabic of the Islamic physician Ibn Jazlah (d. 1100) of Baghdad. This work was completed in Sicily in 1281 by Faraj ibn Salim (fl. 1273-82), a Jewish physician and translator. The text first appeared in print in 1532; therefore, the compiler of 23 P 10 (ii) must have been working from a Latin manuscript .Eugene O’Curry, MRIA, recorded (H&S Catalogue III, p. 644) that the manuscript was bought for the Academy in the town of Galway from Thomas Keady, to whom it had come from the O’Lee family, hereditary physicians to the O’Flahertys. In the course of the 17th century a member of the O’Lee family told a ‘wild story’ of his having been magically transported to the enchanted Island of Hy Brasil and obtaining supernatural knowledge of medical cures there that were recorded in this book. The unusual appearance of the book convinced some people of the validity of this story.

More often they annotate their books with mentions of where they have written down certain texts; they comment on the weather, or on the hospitality of the household in which they are staying, and generally note the date of writing. From these snippets of information we can begin to build up a picture of the peregrinations of these doctors around the country, as they treat their patients and spend time with their families. Prominent medical families in Connacht included Ó Fearghusa (Fergus) and Mac an Leagha (MacKinley), physicians to the O’Flahertys; in Leinster, the Ó Bolgaidhe (Bolger) and Ó Conchubhair (O’Connor); in Ulster, Ó Caiside (Cassidy), physicians to the Maguires of Fermanagh, Ó Duinnshleibhe (Dunlevy), who looked after the O’Donnells, Ó Siadhail (Shiels, O’Shiel), physicians to the MacMahons of Oriel; in Munster, Ó hIceadha (Hickey), physicians to the O’Briens of Thomond, as well as Ó Leighin (Lane) and Ó Nialláin (Nealan/Niland). Brief details of some of the key authorities on whose works these texts are based may be found here.

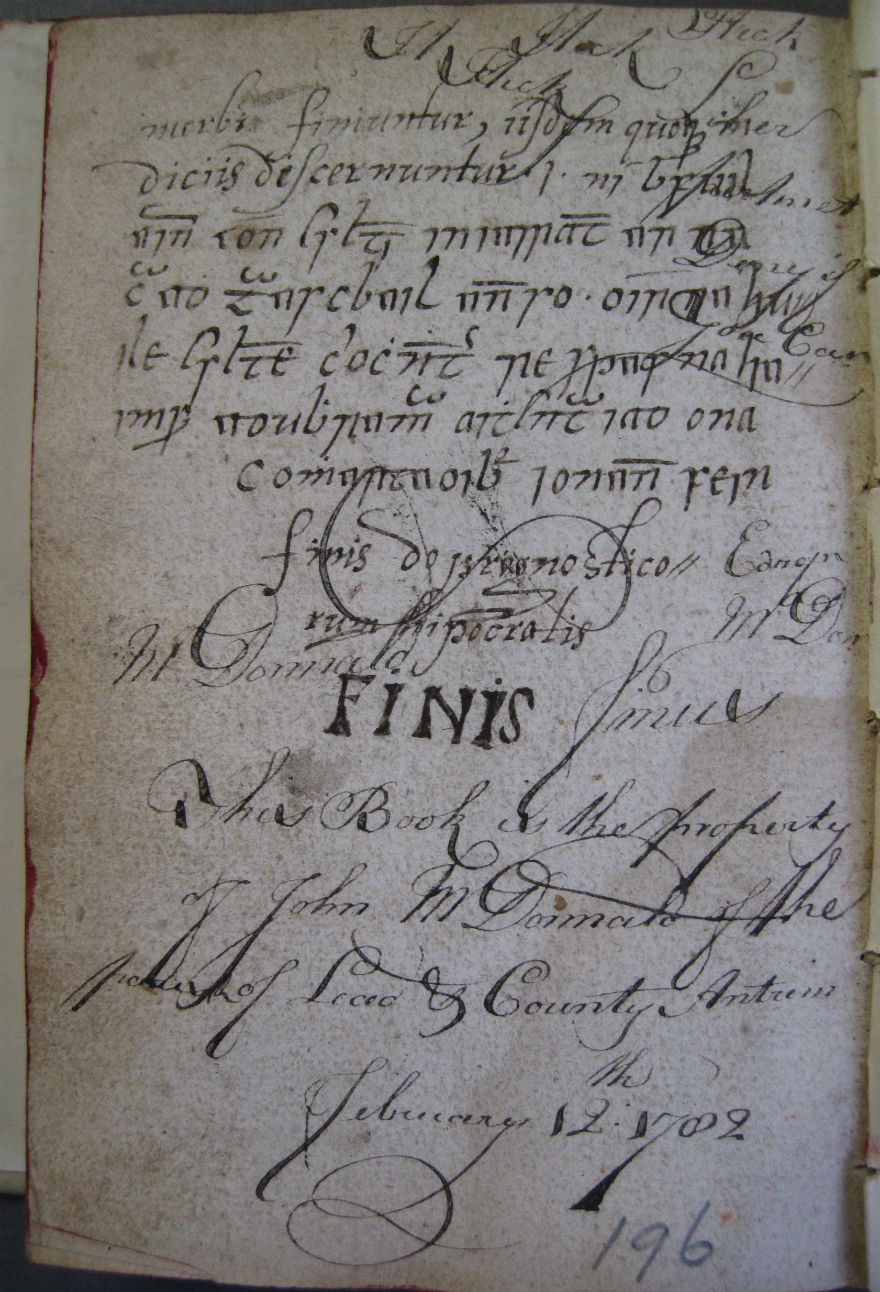

RIA MS 24 P 22 (Reeves Collection), p.196, 17th century

This medical tract contains the Aphorisms and Prognostics (Prognostica) of Hippocrates, with accompanying commentary by Gulielmus Copus of Basel, 1461-1532.

The manuscript also contains the text of Aegidius’ much-cited work, De urinis, which deals with kidney stones, the various colours of urine etc. Note the use of Latin for the headings and introductory sections, referencing the original text on which the translation is based. p. 196 above attests to the manuscript’s ownership by John McDonald, parish of Lead (Layde), Co. Antrim in the late 18th century, and there are copious marginal notes and iou’s from this period scattered throughout the document. It was later owned by Bishop William Reeves.

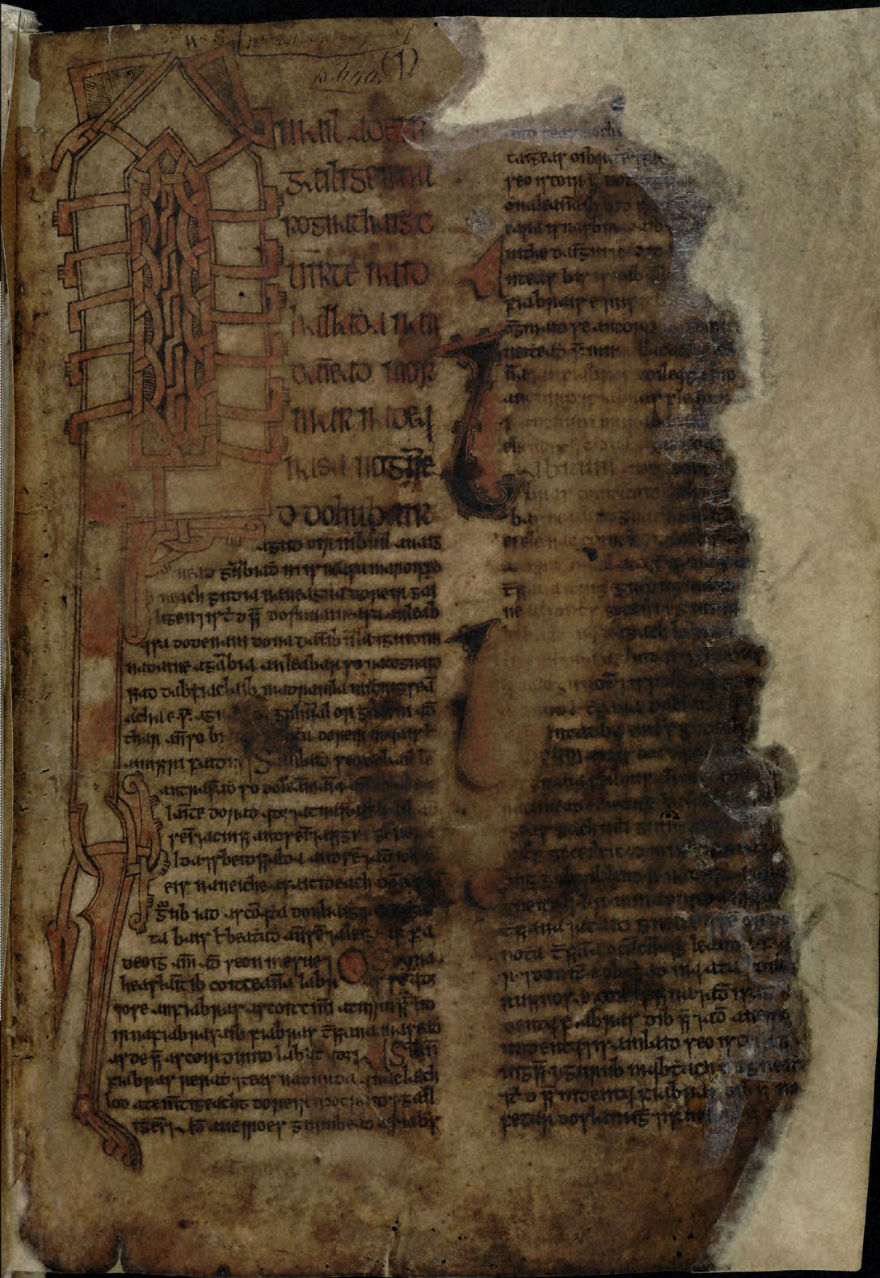

RIA MS 24 P 14 is an important copy of the Lilium, whose scribe Corc Óg Ó Cadhla (fl.1577-84), was a Leinster-based physician. It was written 1577-8 at Teagh na Ronna (Tinnaranny, Co.Kilkenny), Graiguenamanagh, Co. Kilkenny and Lia Ailleacainn (Lissallican, St Mullins, Co. Carlow). It is the only complete copy of the Irish Lilium extant. This manuscript was owned by Edward O’Reilly, then by Robert MacAdam, who purchased it for 11s. at the O’Reilly library sale in 1830. Its last private owner was Bishop William Reeves. The O’Reilly sale catalogue refers to it as follows: ‘the subject medicine, written in the School of Montpelier in the year 1305; the book is perfect …’. On p. 76a, the physician-scribe is starting to copy the Lilium at Tinnaranny and on p. 170a, we see him completing part 3:

22 la do mhi mharta agus a nGrainsigh na Manach a bfochuir Briain mic Cathaoir mic Airt Caomhanaigh do crichniges e …

In Graiguenamanagh, in the company of Brian, son of Cahir, son of Art Kavanagh, I completed it on 22 March …

In his reference to Graiguenamanagh, Corc mentions that he treated the two daughters of Brian Caomhánach, chief of his sept, for menstrual irregularity. This is one of the few allusions made to the active treatment of female patients in these manuscripts –

… 7 me ag leiges a deise ingen o hsechran fola mista

… while I was treating his two daughters for a menstrual irregularity.

To view RIA MS 24 P 14 in full go to www.isos.dias.ie.

RIA MS 24 P 14 (Reeves Collection), p.76a, 16th century

RIA MS 24 P 14 (Reeves Collection), p.170a, 16th century

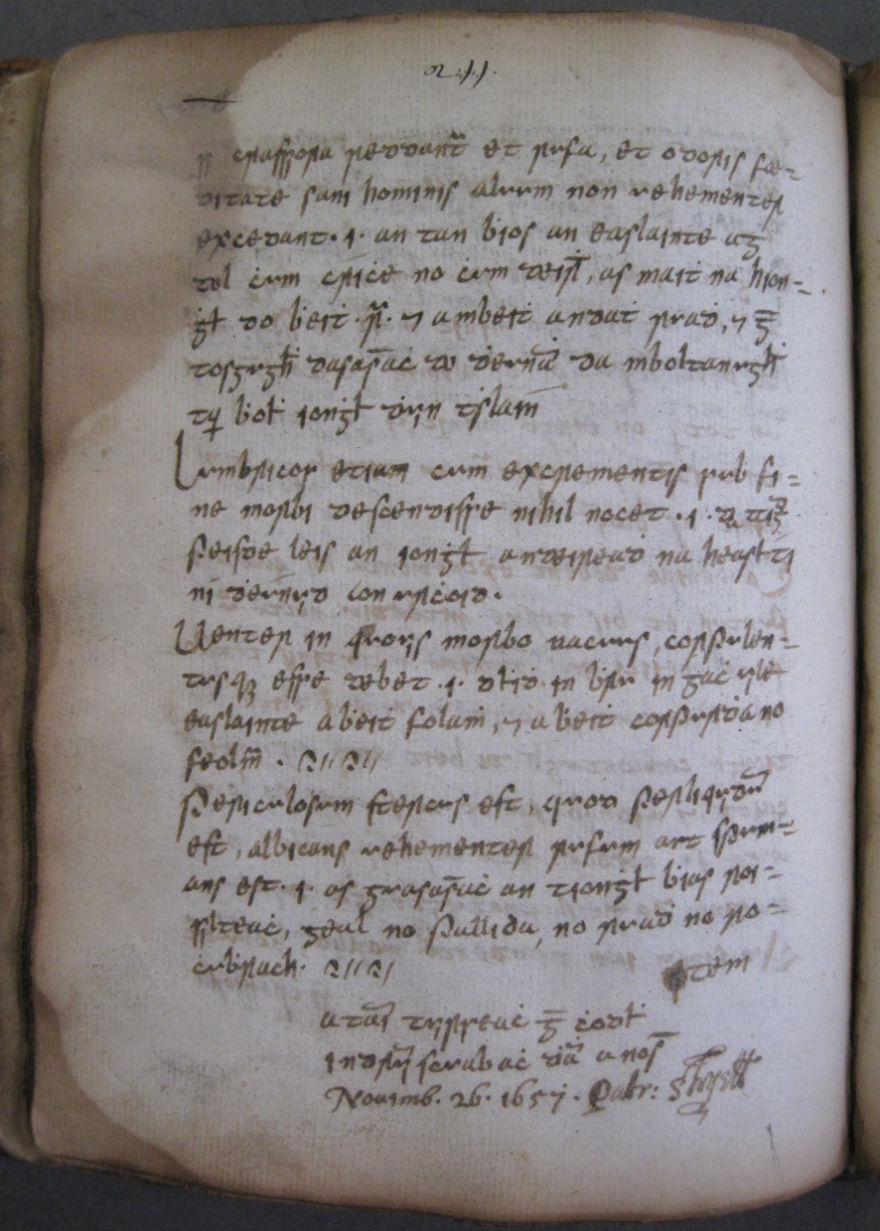

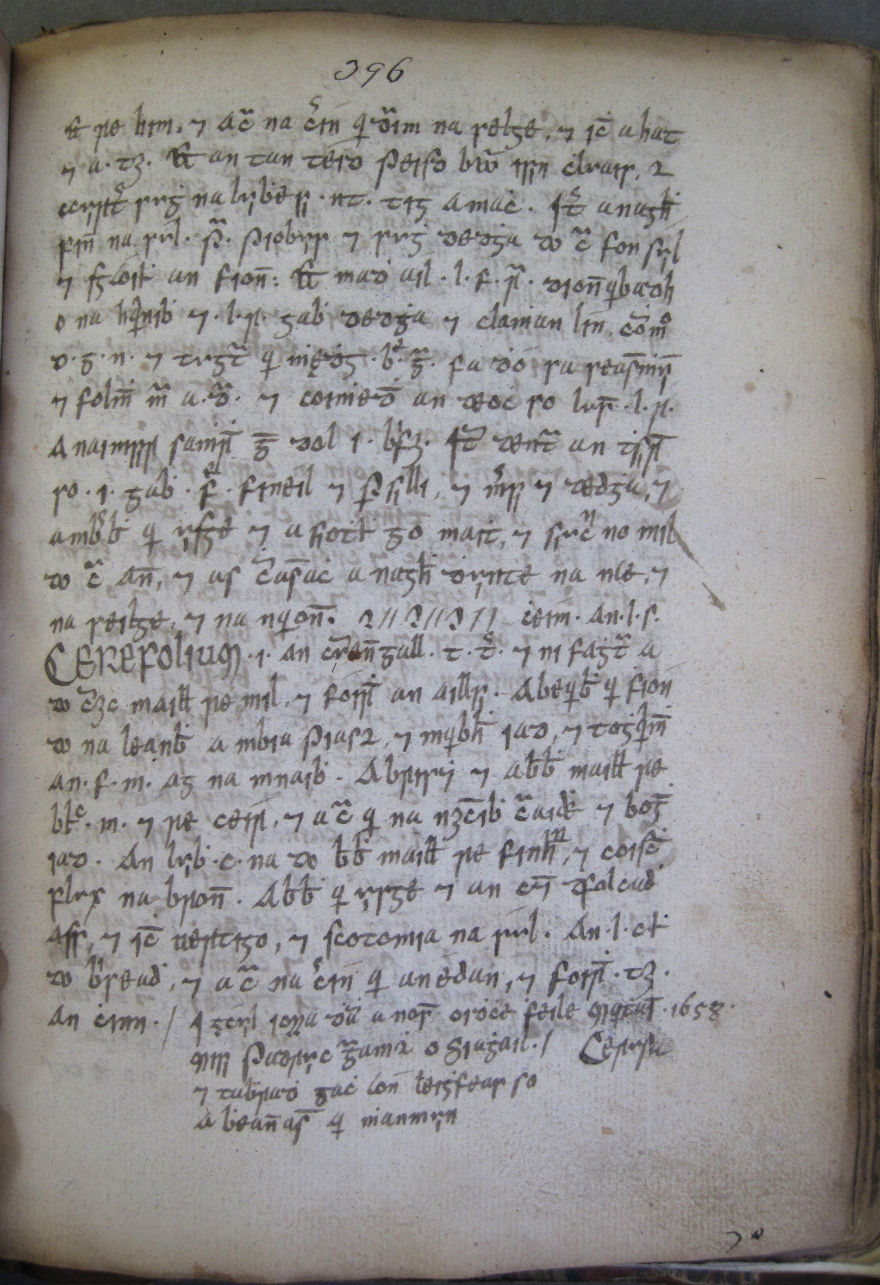

RIA MS 23 K 42, the Book of the O’Shiels,17th century, is a compendium of medical treatises, written by Pádruic Gruamdha Ó Siadhail, a native of Ibh Eathach (Iveagh) at various locations, 1657-8. It contains the Aphorisms and Prognostica of Hippocrates, Aegidius’ De urinis, Bernard of Gordon’s Lilium, particula prima, on fevers, with extracts from Valescus de Taranta, 1382-1417, interspersed by extracts from Galen and Avicenna. As in many of the other medical manuscripts, we see the writer close up, as on p. 211:

ataim tuirseach gan chodladh – I nDruim Scuabach dham anocht – Novembr. Patr: Shyell

I am tired for lack of sleep – I am in Drumscoba tonight – 26 November 1657

Drumscoba is in the barony of Attymas, Co.Mayo; and on p. 396:

I gCúil Iorra dhamh anocht Oidhche Fheile

Martain, 1658. Misi Padruic gruamdha Ó Siaghail: agus tabhradh gach áon leighfeas so a bheannacht ar mh’anmuin

I am in Killaspugbrone tonight, St Martin’s Eve, 1658. I am grim Pádraig O’Sheil: and let everyone who will read this bestow a blessing on my soul.

Killaspugbrone is in the barony of Carbury, Co. Sligo.

RIA MS 23 K 42, p.211, the Book of the O’Shiels,17th century

RIA MS 23 K 42, p.396, the Book of the O’Shiels,17th century

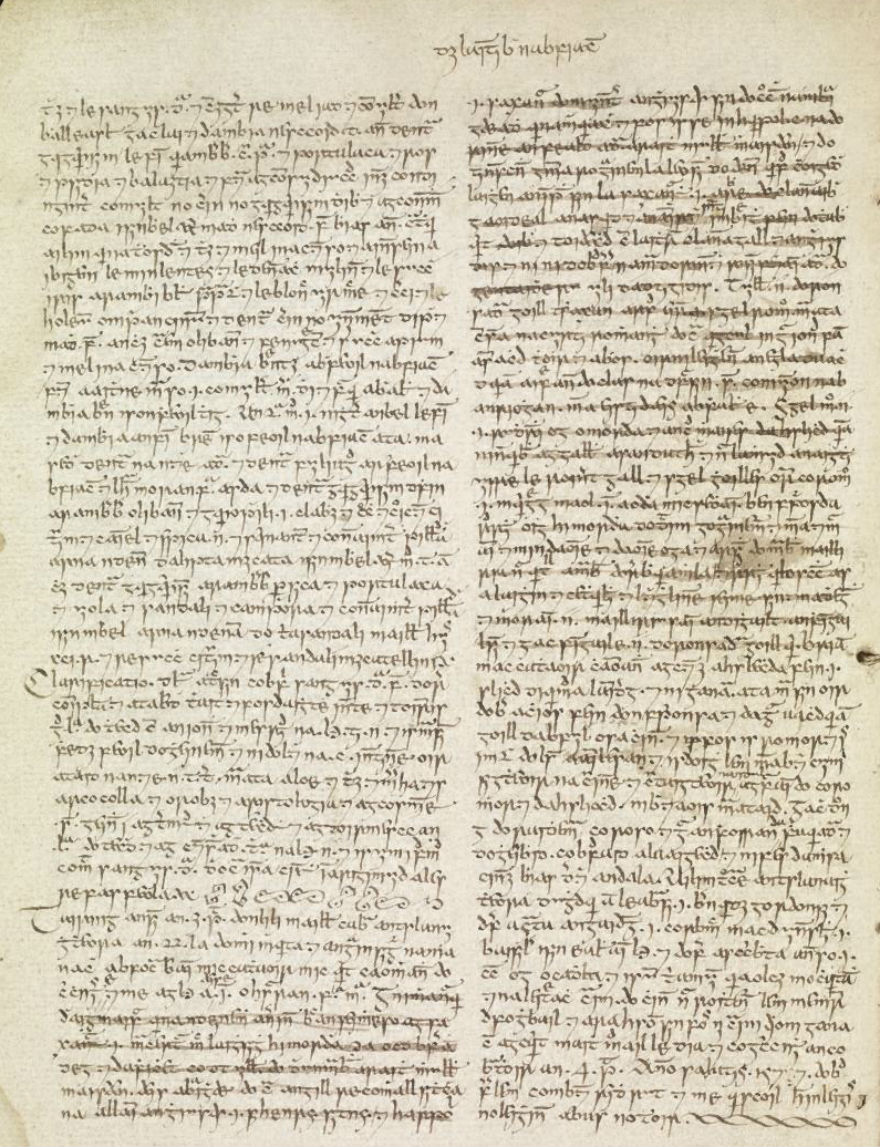

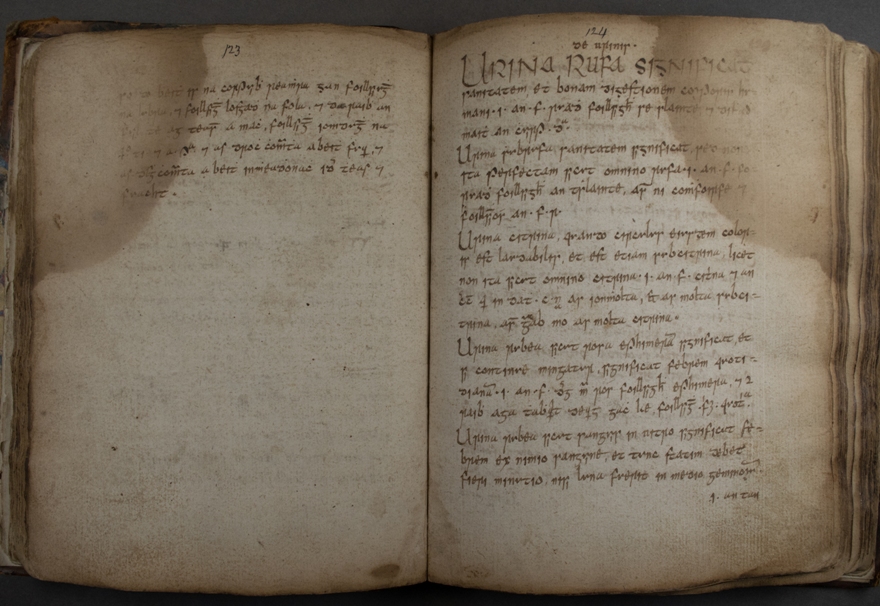

See RIA MS 23 K 42, pp. 123-4, below, showing the end of Hippocrates’ Aphorisms, Bk 7 and the beginning of Aegidius’ De urinis, specifically on the significance of the colours of the urine. This tract was used as a working document ─ the O’Shiels were hereditary physicians to the MacMahons of Oriel (Airgialla), in the north-east of Ireland. The same applied to most of the medical manuscripts. These were not prestige works. Their purpose was practical.

RIA MS 23 K 42, pp.123-4, the Book of the O’Shiels,17th century

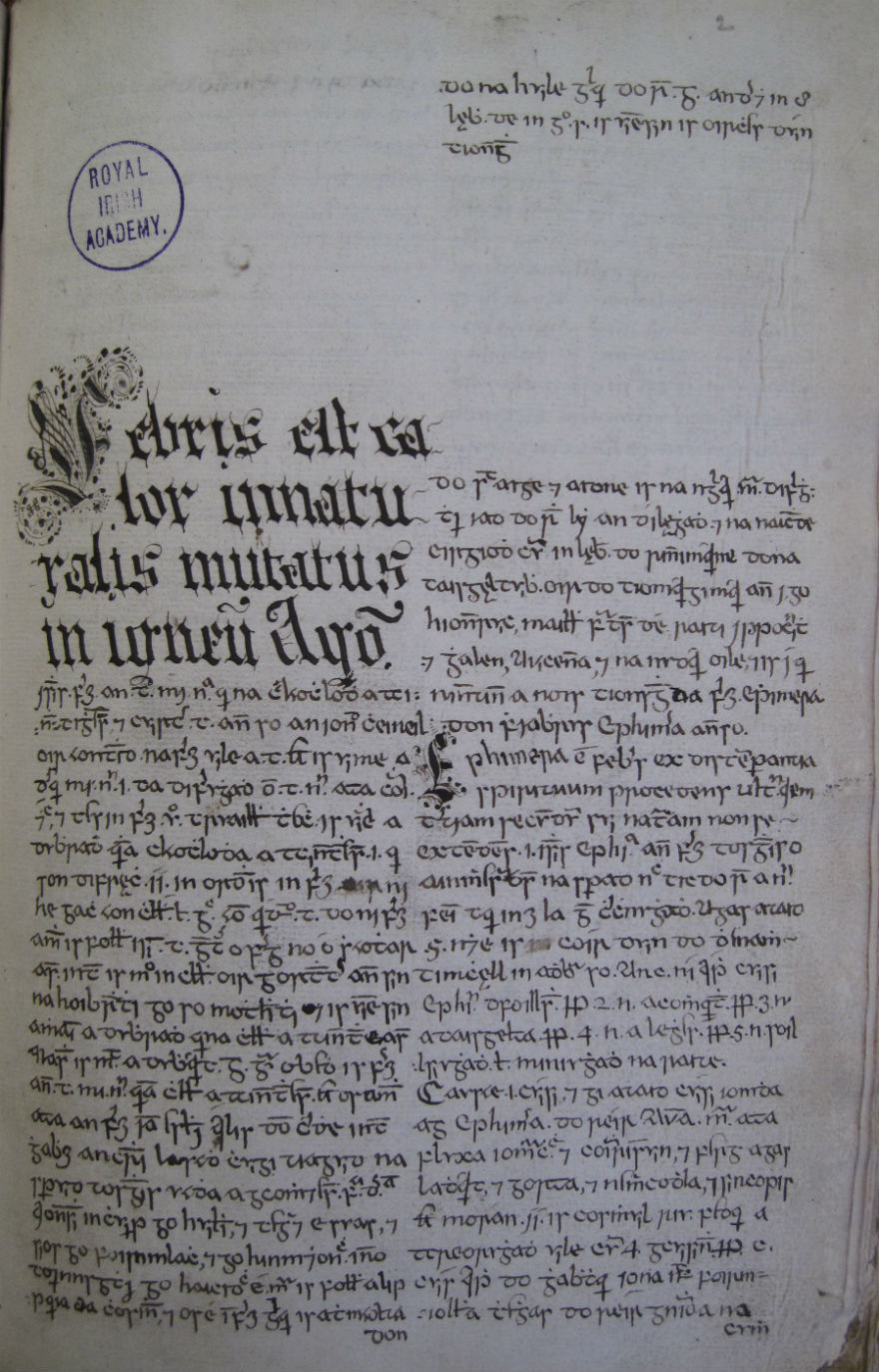

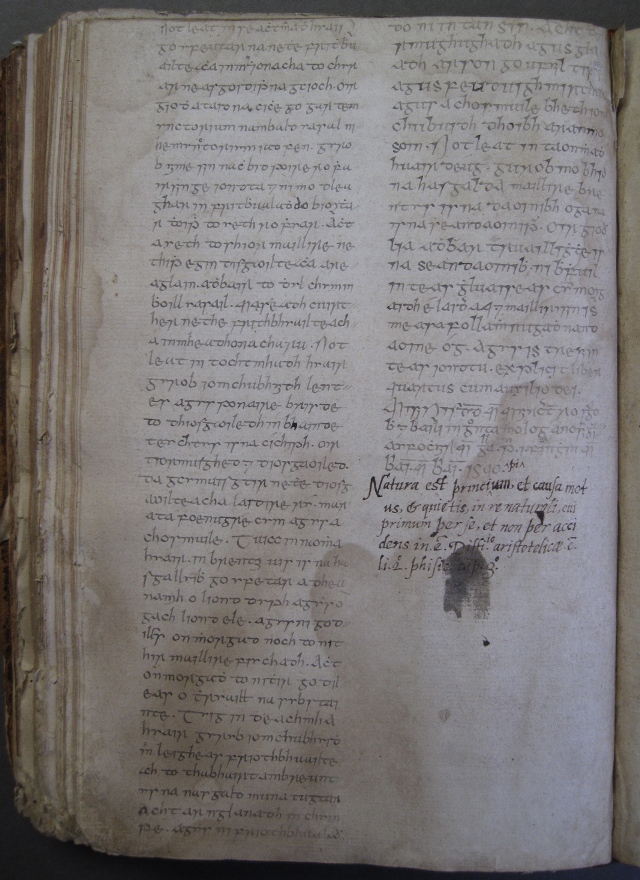

RIA MS 3 C 19, sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, was written by Risteard mac Muircertaigh Ó Conchubhair, 1561-1625, with some replacement leaves written by Tadhg Ó Neachtain, 1671- c. 1752 and another scribe a century and a half later. Ó Conchubhair was a member of the medical school at Aghmacart, Co. Laois, run by the Ó Conchubhair in the Mac Giolla Phádraig lordship of Upper Ossory. Risteard made this copy of the Lilium from an exemplar written by Donnchadh Óg Ua Conchubhair, fl. 1581-1611, who was ollamh leighis to Finghin Mac Giolla Phádraig. We learn from a comment in this manuscript that Donnchadh Óg had studied medicine in Ireland exclusively –

Donnchadh Óg Ua Conchubhair .i. ullamh Osraighi (re leghes 7 rogha legh Erenn ina aimsir fen tuig riot gan dul a hÉirinn do dhenam foghluma

The best of the doctors of Ireland in his own time – and that without leaving Ireland to study

Dr A. Nic Dhonnchadha considers that this indicates that the medical education on offer in Ireland at the time was regarded as being on a par with that on offer on the continent. The contents of the manuscript include versions of Bernard of Gordon’s Lilium, the Decem Ingenia and Prognostica. Folio 2r begins – ‘Febris est calor innaturalis’ – ‘Fever is unnatural heat’ – a tract on fevers.

There is a considerable amount of personal scribal information in this manuscript:

Tairrnic ann sin in treas partical don Lili maille cabhair an tslanuightheora. An 18 la do November …

There finished, with the help of the Saviour, the third part of the Lily. The 18th of November …

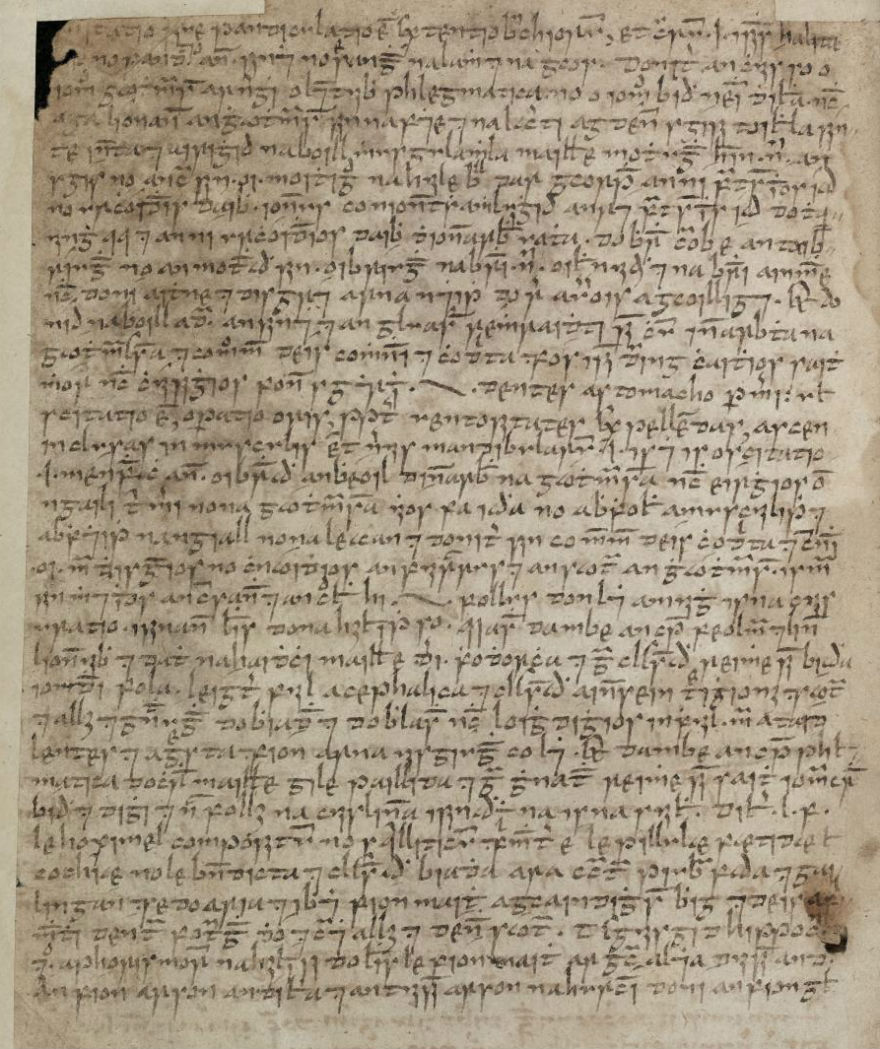

RIA MS 3 C 19, f.2r, 16th and 18th centuries

Risderd Ó Conchubhair was at Courtstown, Co. Kilkenny, at this time, having begun the Lilium at Cullahill Castle, Co. Laois, on 7 May that year. There follows a long note recording the hospitality of the couples, in five counties, with whom he had stayed during this time. He particularly mentions the role of Gráinne, daughter of Brian Mac Giolla Phádraig and wife of Edmund Butler, second Viscount Mountgarret, in promoting his education from the age of twelve onwards, that is after the death of his father. A further note occurs on folio 145v:

Misi Risderd mac Muircertaigh rosgriobh agus Baile in Gronta mo log a nOsraighi a bfochuir mic Gilla Patruic i Finghin mac Briain mic Briain. 1590.

It is I, Risderd son of Muircheartach, who wrote [this] and, Grantstown [bar. Clarmallaigh, Co. Laois] is my place [of writing] in Ossory, in the company of Mac Giolla Phádraig, i.e. Finghin son of Brian, son of Brian. 1590.

To view this manuscript in full go to www.isos.dias.ie.

RIA MS 3 C 19, f.145v, 16th and 18th centuries

RIA MS 23 N 16, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, scribe not named, was compiled at a number of locations, including Cell Breacain (Killbrackan, Co. Laois), between the years 1596 and 1610. The contents include commentaries on Hippocrates’ Aphorisms and Prognostics, Aegidius’ De urinis, treatises by Niccolò Bertruccio, d. 1347, Geraldus de Solo, fl. 1330-40, Lanfrancus de Mediolano, c. 1250-1306, Galen (on dropsy), Avicenna (on paralysis), and other medical matter. Bertruccio was a physician, anatomist and professor of medicine at the university of Bologna. His Collectorium was first printed at Lyon in 1509. The only extant Irish version of the section of his treatise which deals with Stretching and Yawning ─ De alitatione et oscitatione ─ is to be found in this manuscript, beginning on f. 122v, ‘Halitatio …’. Originally translated by Donnchadh Óg Ó Conchubhair, fl. 1581-1611, chief physician to Fighnin Mac Giolla Phádraig, lord of Ossory, Donnchadh is mentioned a number of times in the manuscript. Reference is also made to Aghmacart, site of the famous medical school in Co. Laois:

Anno domini 1596 an 13 la do Maius. a nAchaidh mhic Airt dam an tansa a bfhochair Dhonnchadha óig í Chonchubhair agus is urusa dhamh anois bheith dobrónach óir adime mo charaid agus mo chumpanach uaimh = Mairghrég inghen Donnchadh agus dar an leabhar ní fes dam créd do dhén ina hégmuis fesda.

On 13 May in the year of our Lord 1596, I am in Aghmacart now in the company of Donnchadh Óg Ó Conchubhair. And it is easy for me now to be sad for my friend and my companion has left me, i.e. Mairghrég, daughter of Donnchadh, and upon my word I don’t know what I shall do without her from now on.

To view this manuscript in full go to www.isos.dias.ie.

RIA MS 23 N 16, f.122v, 16th and 17th centuries (Betham collection)

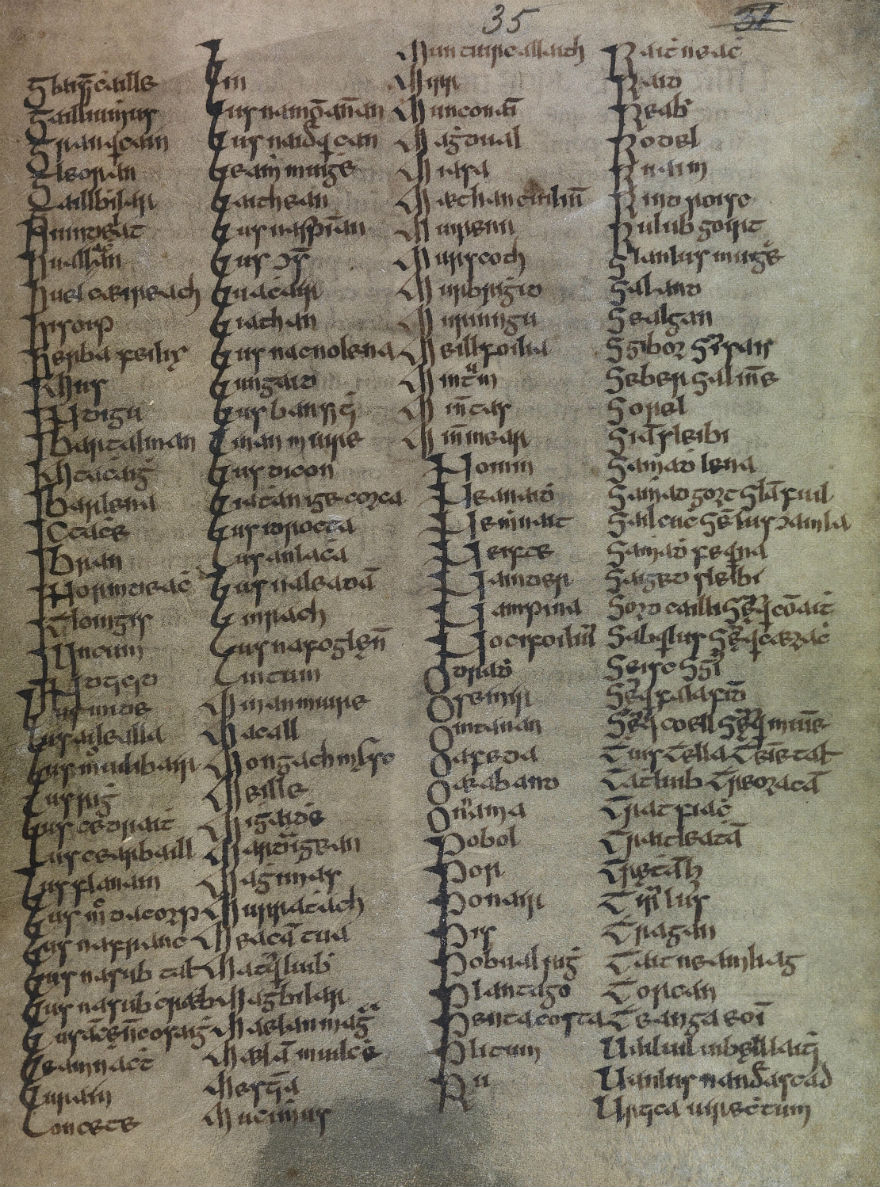

RIA MS 23 O 6, early fifteenth century, consists of four manuscripts bound together, a miscellany of medical material; the former owners and scribes are not known. Various sources are cited, including Aegidius’ De urinis, Galen, Avicenna, Bernard of Gordon et al. Contents include lists, e.g. the ingredients of poison and antidotes; colours of the urine; and properties of beans and barley. A list of plant names occurs on p.35 shown here. Botany was an important element in medieval medicine and Irish doctors were renowned for their knowledge of the properties of plants.

To view this manuscript in full go to www.isos.dias.ie.

RIA MS 23 O 6, p.35, early 15th century

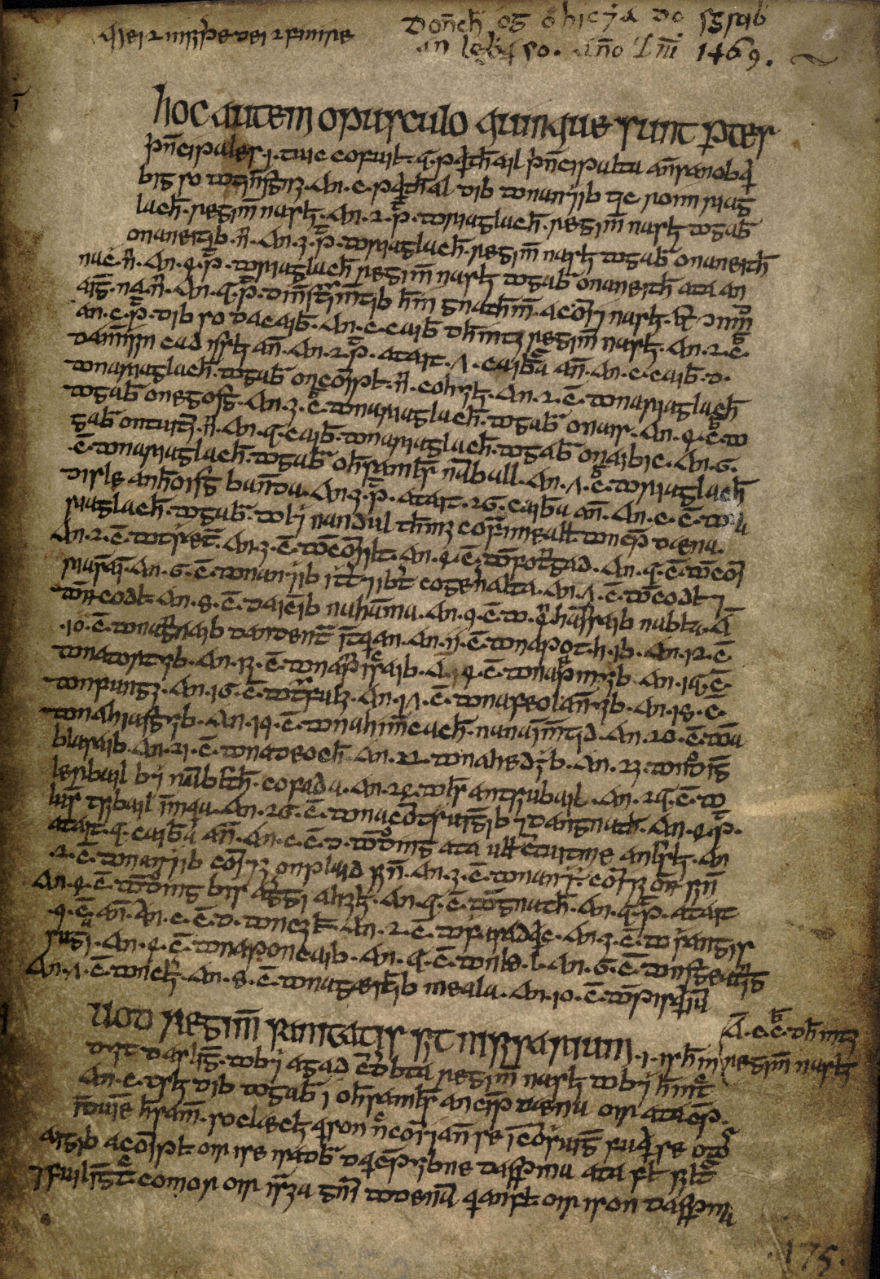

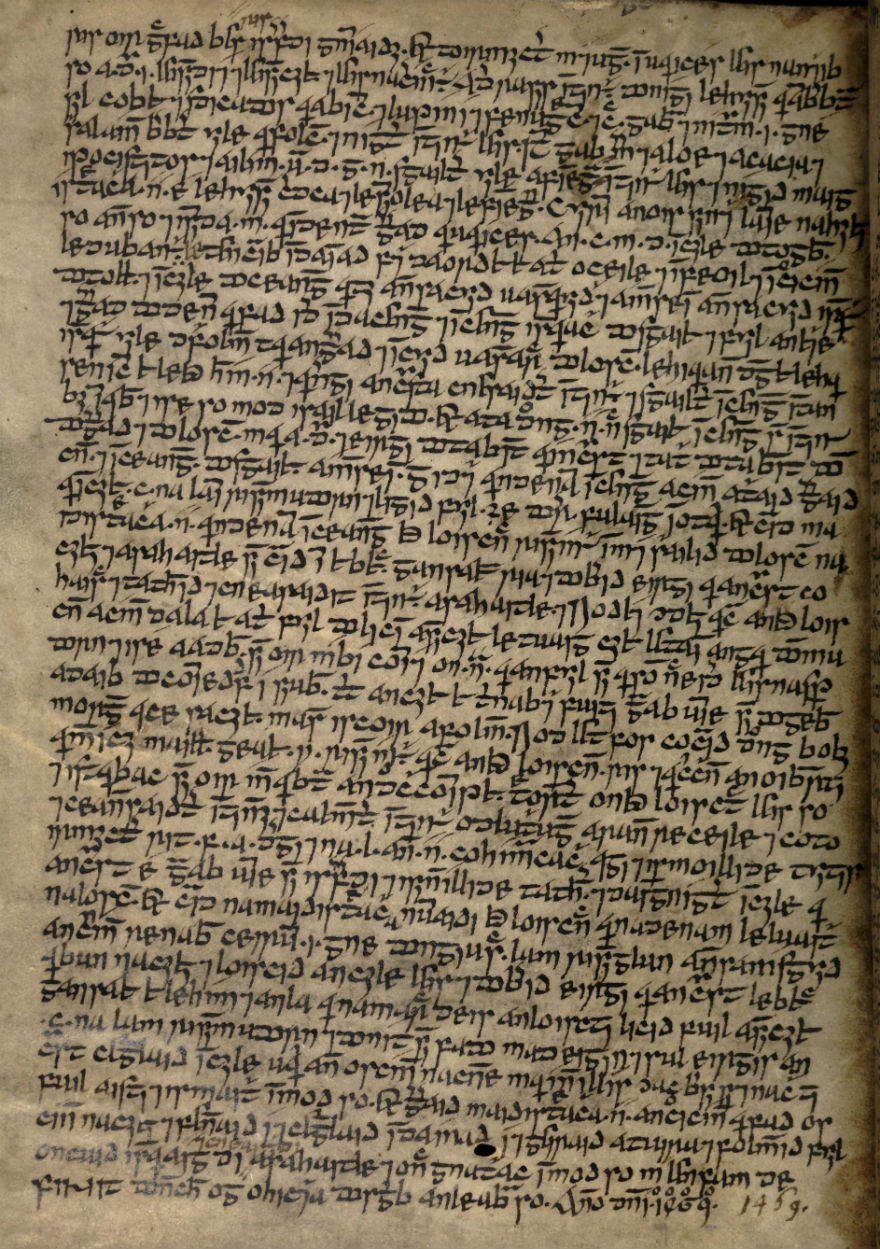

RIA MS 24 P 26, A.D. 1469, written by Donnchadh óg Ó Híceadha. The O’Hickeys were physicians to the O’Briens, MacNamaras and other families of Thomond; it contains Geraldus de Solo’s commentary on Rhazes’ Almanzor, Pietro de Argelato’s De chirurgia and Arnaldus de Villa Nova’s Regimen sanitatis. Owned by Belfast engineer Robert MacAdam in the nineteenth century, it was previously owned by Edward O’Reilly (1830 sale catalogue, lot no. 4) and latterly was the property of Bishop William Reeves. Reeves cites the O’Reilly sale data on the flyleaf and notes: ‘I bought it in Nov. 1889 together with a large collection of Irish MSS. from Mr Robert MacAdam, & it is the gem of the lot …’. The book remained in O’Hickey hands for several hundred years; evidenced by annotations therein. See p. 353 below, for the beginning of the Regimen sanitatis. Note Donnchadh Ó hIceadha’s dating of the compilation to 1469 on p.352.

To view this manuscript in full go to www.isos.dias.ie.

RIA MS 24 P 26, p.353, A.D. 1469, (Reeves Collection)

RIA MS 24 P 26, p.352, A.D. 1469, (Reeves Collection)

MS 23 P 20, [sixteenth-century ?], scribe unknown, is a copy of John of Gaddesden’s Rosa Anglica, which includes material not found in the printed version of the text.

John of Gaddesden (Johannes de Gaddesden), c. 1280-1361, is thought to have hailed from Gaddesden on the borders of Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire. He studied at Merton College, Oxford, obtaining degrees in arts, theology and later, medicine. According to Winifred Wulff ’s biography in the introduction to her edition of the Irish translation of his Rosa Anglica (London, [1929]), John was the first eminent English physician to have completed his medical training in England. He used Bernard of Gordon’s Lilium in compiling the Rosa in 1314. Furthermore, the Irish translator of the Rosa borrowed extensively from the Lilium in compiling his translation of the Rosa. John refers constantly to his practice at Oxford. He eventually became court physician to Edward III, whom he is supposed to have cured of smallpox.

Not known for his humility, John explained the title of his text – ‘just as the rose excels among flowers, this book excels among textbooks on practical medicine’. Wulff points out that while there are many reasons to criticise Gaddesden’s text (for example, his poor efforts at interpreting Greek terms – he was widely regarded later as a charlatan), the text has a lasting value for the insights it provides on daily life during the Middle Ages, the remedies used, the contents of the larders, charms etc. – ‘a hot- potch of medical teaching, genuine or fabulous results of the application of remedies, oriental leechcraft and superstition, native English cures and charms, prayers and religious practices, interwoven with the native beliefs of the country’. The Rosa Anglica was first printed at Pavia in 1492.

To view this manuscript in full go to www.isos.dias.ie.

MS 23 P 20, p.3, Rosa Anglica, in Irish, 16th century ?

RIA MS 23 P 10 (iii), a fifteenth-century treatise, formerly owned by Searga Ó Conuill. Probably written in Co. Clare, contains the major part of Book 1 of the Rosa Anglica, the opening page of which is shown here, and has texts by other English authors, Bernard of Gordon and Gilbert the Englishman (Gilbertus Anglicus), c. 1180-c. 1250.

To view this manuscript in full go to www.isos.dias.ie.

RIA MS 23 P 10 (iii), p.1.

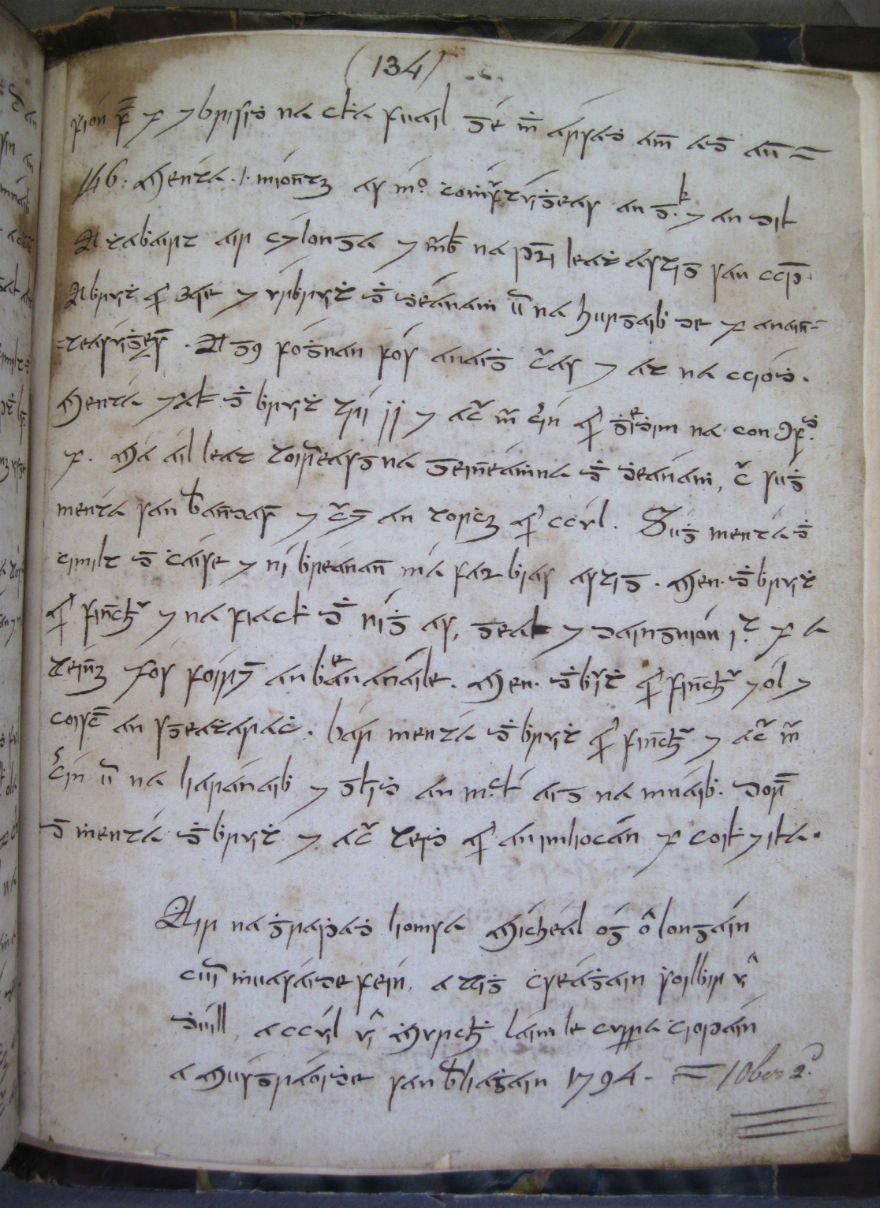

RIA MS 23 N 20, eighteenth-century, this Munster medical miscellany, compiled by Micheál óg Ó Longáin, 1766-1837, for his own use and later owned by Sir William Betham, includes cures and treatments for all kinds of mishaps and ailments including burns, scalds, sore eyes, toothache, warts, sprain and colic, hiccups and nosebleeds, as well as jaundice and obstructions of the liver and lungs. Treatment for the bite of a mad dog also features. Charms are recorded too ─ for example a charm against the ‘evil eye’ and a charm for sprain. Cures for bewitched cows and other affected animals feature also. Ó Longáin’s colophon, written at Coppan, Co. Cork, on p. 134 states:

Air na ghraphadh liomsa Micheál óg O Longáin cuim mh’uasaide fein a

ttigh chSeaghain shoilbhir ui Dhuill a cCuil ui Murchadha laimh le

Curracha Chiopain a Musgraide san mbliaghain 1794, December 2d.

Compiled by me, Michael Longan, for my own use, in the company of

Seán Soilbhir Doyle, at Cuil Ui Murchadha by Coppan in Muskerry, 2

December 1794.

RIA MS 23 N 20, p.134, 18th century (Betham Collection)

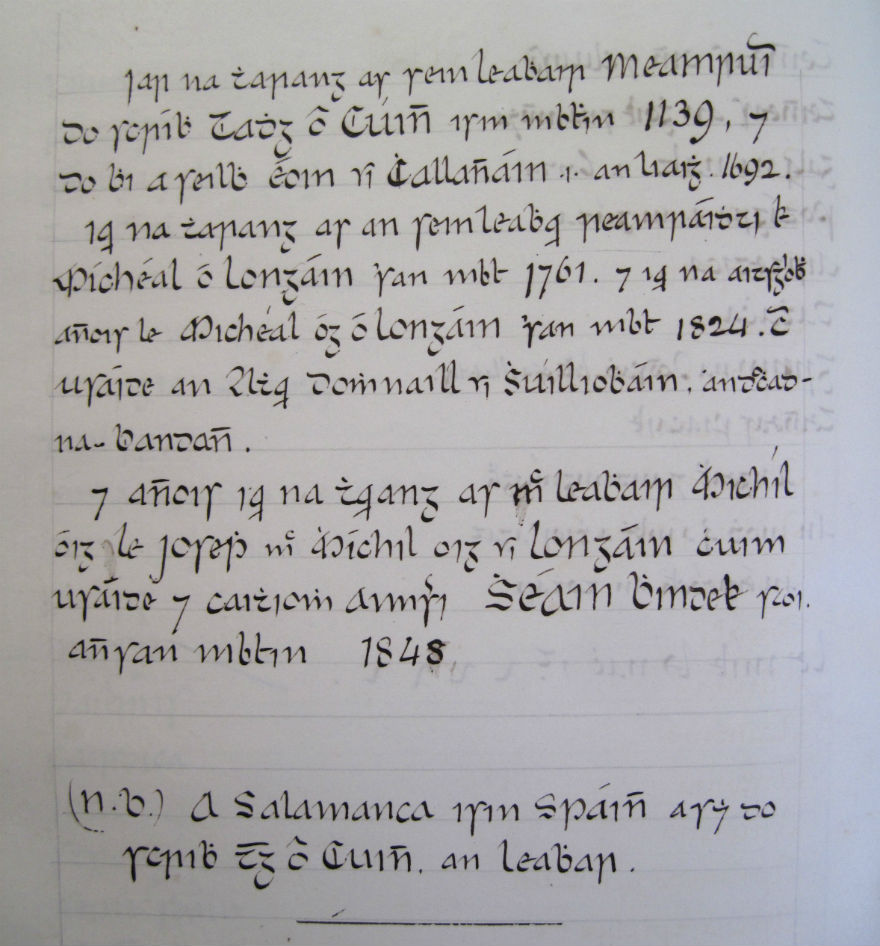

Micheál Óg Ó Longáin also compiled copies of Materia medica, based on a Salamanca exemplar, for Henry Joseph Heard, DD, (RIA MS 3 B 15). Micheál Óg’s youngest son, Seosamh, 1817-80, also made a copy of this text which he attributes to Irish physician Tadhg Ó Cuinn, explaining that it was compiled in Salamanca by Ó Cuinn in 1139. Seosamh Ó Longáin’s copy was made in 1848 for the Cork patron, John Windele, 1806-65. This copy (RIA MS 24 B 2) is shown below.

RIA MS 24 B 2, p.122 (Windele Collection)