On the importance of preserving lantern slide collections

13 April 2023In the latest Library Blog post, Rebecca Cairns explores the photographic collection of Robert Lloyd Praeger (1865-1953) at the Royal Irish Academy.

The Royal Irish Academy acquired the Robert Lloyd Praeger (1865-1953) collection in 1952. Upon intake, the collection had been split into various trunks, which contained hundreds of items relating to the natural sciences—including papers, pamphlets, and photographs. The bulk of the photographs found in the collection are glass plate negatives and prints, many of which were produced by Irish photographer Robert John Welch (1859-1936). Praeger and Welch were avid collectors, and both were active in Ireland’s naturalist circles. Praeger himself had joined the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club (BNFC) at the young age of eleven, and later joined the Dublin Naturalists’ Field Club (DNFC) in 1893.

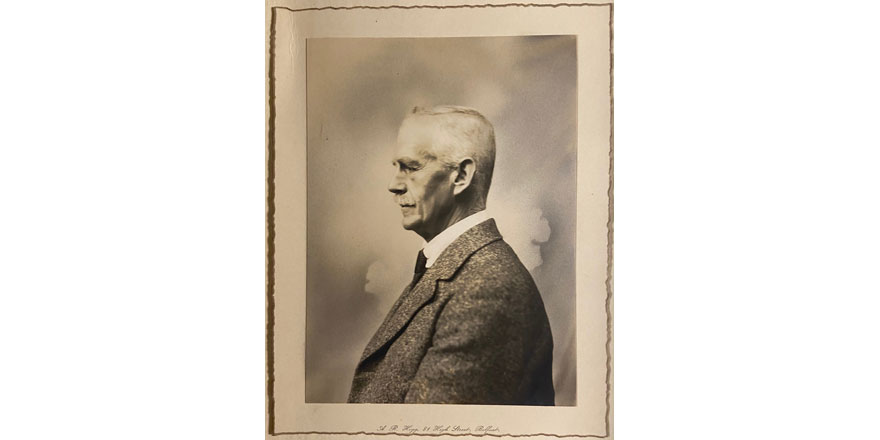

Fig.1 Portrait of Robert Lloyd Praeger, MRIA

photographed by A.R. Hogg (RIA Photo Series 20/Box 2)

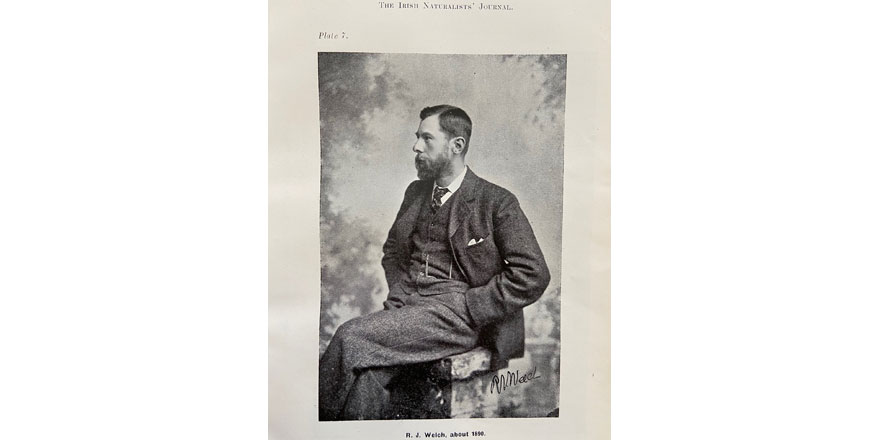

Fig.2 Portrait of Robert John Welch, around 1890

(Irish Naturalists’ Journal, obituary notice for R.J. Welch, vi:6 Nov. 1936)

The field clubs attracted both amateurs and professionals who had an interest in the fields of botany, zoology, geology, and archaeology. As many of Praeger and Welch’s photographs make clear, members frequently attended expeditions throughout Ireland to study, observe and collect ‘specimens’. The specimens—as well as the photographs of them—would later be shared with others during meetings.

Fig.3 “The way some Irish Naturalists studied nature,” Belfast and Dublin Naturalist Field Clubs taking tea at Slieve Glah, Cavan, July 1896.

R. L. Praeger is standing to the left of the table Photographed by Robert John Welch (RIA Photo Series 18/Box 7)

Alongside Welch, other well-known photographers from Ireland—including Alexander Robert Hogg (1870-1939) and William Alfred Green (1870-1958)—played an important role within these naturalist circles. The photographs made during expeditions reflect various areas of the natural sciences: expansive landscapes, colonies of seabirds, or fragments of corals and seaweed. Photographs of materials found across Ireland serve as proof of the discovery of new species of wildflowers, of molluscs and other curiosities. The images helped others understand the geology, flora and fauna of the island.

Fig.4 “On the Limestone Terraces of the Burren, Co. Clare” photographed by Robert John Welch.

History of the Lantern Slide

During field club meetings, a lanternist would project photographic images produced from expeditions onto a screen so members could observe the images in detail and discuss them. The photographs that were being projected were called lantern slides; projected through a magic (or optical) lantern.

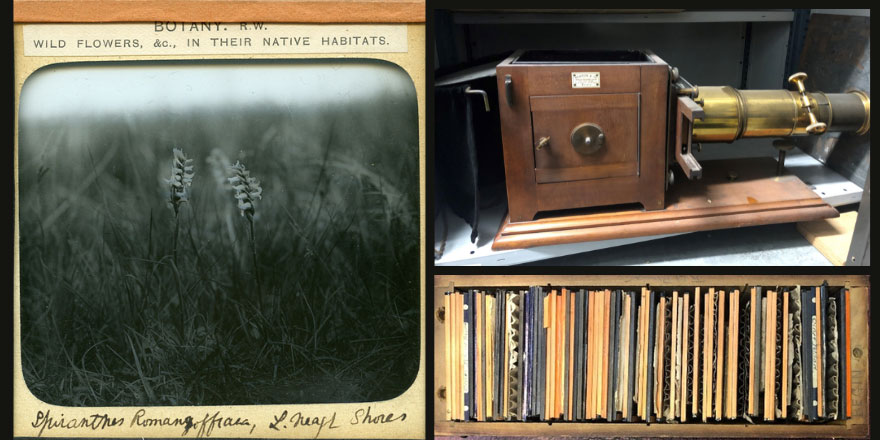

Fig.5 Lantern slide projector at the Royal Irish Academy Library

The earliest known lantern shows can be traced back to approximately 1720, but it was between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when projection had become exceedingly popular in the field of entertainment. Lantern slides would later become integral for education and research. When used for entertainment, a lantern show would usually consist of an audience seated in complete darkness; a narrator guiding people through an engrossing story while a projectionist flipped the slides. When the lantern slide industry began to shift away from entertainment and towards education, slides were produced in large quantities by manufacturers across Europe and North America and were distributed globally.

Lantern slides were commonly used in the fields of natural history and sciences because they allowed for the sharing of images of specimens and scientific findings with large audiences. For example, a lecturer could share an image of a specimen which had been photographed microscopically: such as details of a tendril, the comb fragments of a beehive, or the intricate patterns found on the wings of a butterfly. They were also popularly used within the field of medicine.

Fig.6 & 7 Two handmade lantern slides. The image of the nest has been hand-painted. The image on the right has a skewed appearance,

which suggests this is a handmade (rather than a commercially produced) slide.

What is a Lantern Slide?

There are two standard sizes of lantern slides: 8.3 x 8.3 cm (European format) and 10.16 x 8.25 cm (American format). The image on the slide might have been produced by one of several historic photographic processes (such as collodion, albumen, or silver gelatin). The photographic image is covered with an identical sized piece of glass, which is held in place by four strips of gummed tape around the support. Another identifying feature of lantern slides is a decorative or rounded border framing the image, featuring a descriptive text which explains the content of the image.

In collections today, one is likely to find slides produced by any number of different commercial manufacturers. However, it is worth noting that many photographers chose to produce their own slides. These can usually be distinguished from commercially made slides by observing handwritten captions on their exterior; or hand-coloured sections of the images themselves.

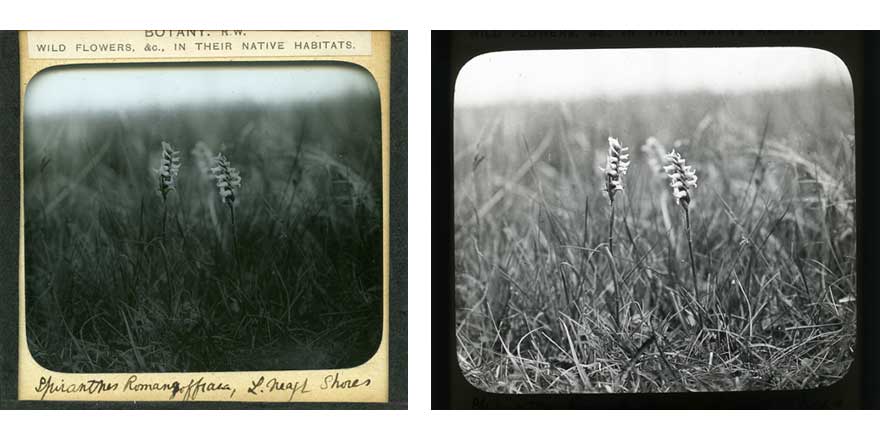

Fig.8 & 9 A lantern slide with an image produced by R. J. Welch. The image is of Spiranthes romanzoffiana, or ‘Irish Lady’s Tresses’. The handwritten inscription suggests that the slide was handmade. Note the same image on the right,

which was produced with a flat-bed scanner and was processed as a photographic positive. The image shows the detail of the original photograph and gives us a sense of what it may have been like to observe this image while it was being projected.

The Praeger Collection & Issues in Collections

The Praeger collection held by the RIA Library contains glass plate negatives, photographic prints and several hundred lantern slides which are currently being transferred from original small wooden carrying cases to archival-grade boxes and enclosures. The slides have not yet been catalogued or digitised which means that there are many items from Praeger’s invaluable collection which have not yet been seen or been made accessible to staff and researchers.

Fig.10 An example of a set of Praeger’s lantern slides which were originally stored in a small wooden carrying case.

Since the original photographic image is covered in a piece of support glass which is tightly fastened with tape, it is common for people to believe that lantern slides are stable. They were, after all, made for the sake of being projected; for being handled by lecturers while they quickly flip through slides during presentations. Glass is also understood to be longer-lasting than paper, so other photographs found on glass supports are—like lantern slides—often not prioritised for preservation. Despite the stability (or inherent durability) of lantern slides, both their glass supports and the images on them are at risk of degradation.

Unfortunately, these important photographic resources remain inaccessible within many collecting institutions—which is currently the case with items from the Praeger Collection. Lantern slide collections are important to tend to as they are integral to understanding the history of photography and nature of photographic reproductions, and of the growing use of photography for commercial ventures. They are important historical and educational resources which tell us the stories of how knowledge was transmitted and shared. In the case of Praeger’s collection, the images offer us the opportunity to learn about the history of the natural sciences, and more generally – the history of Ireland.

Moving Forward

Over the next year the lantern slides will be rehoused, digitised, and catalogued in hopes of making images from Praeger’s collection more accessible. The process requires research, resources for housing materials, and quite a bit of patience, but the rewards will be gratifying. Please keep an eye on our website and social media channels (@Library_RIA on Twitter or @rialibrary on Instagram) for updates on this project.

By Rebecca Cairns, Library Assistant, Royal Irish Academy